ST. JOSEPH, MINN. — Patty Wetterling spread the snapshots of her son Jacob across the dining room table. Jacob blowing out birthday candles. Jacob riding a horse. Jacob running a three-legged race with his best friend, Aaron.

Smiling, always smiling.

Some were photos that never had left the album. Others, including Jacob in a bright yellow sweater, had been broadcast around the world.

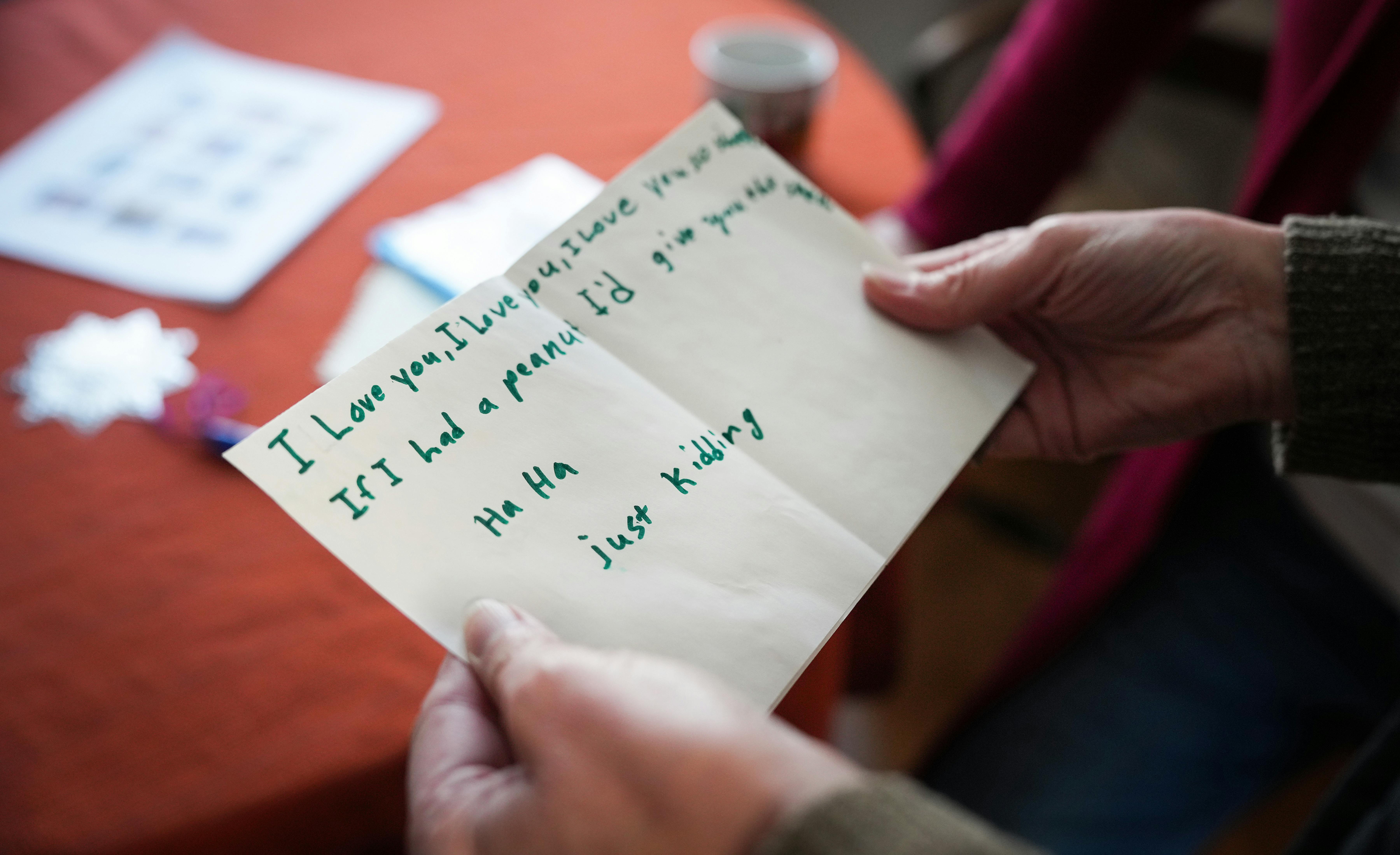

"I found this, Joy, in the pictures," Wetterling said, handing a small card to Joy Baker, who on this February morning was picking images to include in the book they'd written together, "Dear Jacob: A Mother's Journey of Hope."

Baker read aloud the note from Jacob, written in green marker: "I love you, I love you, I love you so swell. If I had a peanut I'd give you the shell.

"Ha ha. Just kidding."

Baker and Wetterling laughed. Wetterling's eyes misted, not for the first time that morning. It was Jacob's birthday. In the years since Jacob was kidnapped from a dark rural road in 1989, at age 11, Wetterling often wrote notes to Jacob on birthdays and holidays, days when the missing deepened. "Dear Jacob," they began.

This card, tucked into the photographs, felt a little like Jacob writing back.

Baker nodded, knowing, and squeezed Wetterling's shoulder.

When they met a decade ago, such a squeeze seemed unlikely. Wetterling was wary of Baker, who was blogging about Jacob's case and who seemed to be just the latest of the interlopers and wannabe investigators looking for a piece of the story.

But over the course of the investigation — one that Baker pushed forward — the pair became close. So close that when Wetterling decided to tell her own story at last, she turned to her friend.

This October, near the anniversary of Jacob's abduction and killing, the Minnesota Historical Society Press will publish the memoir Wetterling and Baker wrote together, a behind-the-scenes look at a crime that shaped the state and the mother who refused to let it steal her hope, her kindness or her marriage.

"From the very beginning, I told her, 'Patty, there are other mothers who have lost their children, and there are other mothers who have missing children,'" Baker said. "'But there's no one like you who has gone on and changed laws and caught the attention of Congress and the president and spoke and made such a difference.

"'I think people want to know what you're made of and where you came from.'"

Writing the memoir together was its own journey, a story they tell like a married couple, with jokes and asides, finishing one another's sentences. Wetterling would write a page and Baker would pick out a detail, saying: "Tell me more."

"'Tell me more about this, tell me more about that,'" said Wetterling, 73, chuckling. "'Tell me more' really bit me in the butt.'"

Sometimes, though, Baker would question Wetterling's openness.

"At several points, I was like, 'Are you sure you want to share that?'" said Baker, 56. " ... It's a very raw, very real story of what families go through."

Somehow, after a quarter-century of searching, of failed leads and false confessions, of meeting "so many dishonest, unscrupulous and dangerous people," as she puts it in the book, Wetterling remained open. Open to the stories that people tell her in parking lots about their own children, their own losses. Open to Baker, who at first seemed "stalker-ish" but who turned out to be who she said she was — "just a mom helping another mom."

The pair started writing in 2015. Not long after that, news broke of Danny Heinrich's arrest and, later, his confession. In 2016, he directed investigators to a farm field in Paynesville, Minn., where they dug up Jacob's red hockey jacket, first, and then his remains.

Suddenly, Wetterling was no longer searching, no longer sure of who she was. The book would have to wait.

'Who was this Joy Baker?'

At a gala in Willmar, Minn., in 2013, a tall blond woman handed Wetterling her card.

"I'm not sure if you've heard of me," Baker said, "but I have a blog called Joy the Curious, and I've been writing about Jacob's case for the past few months."

Over the years, "I'd been handed many cards by people who had written books, articles, short stories or poems, but blogging was new to me," Wetterling writes in her memoir, according to excerpts provided by the publisher. "I'd never read a blog.

"Who was this Joy Baker, and what the heck was she writing?"

The next morning, Patty's husband, Jerry, read the first entry, from 2010, aloud: "Where are you, Jacob?" it began. "Twenty-one years, and still no trace." Baker wrote as a mother, who thought of her two sons, then in their teens, as she stared down the road where a masked man with a gun had appeared, confronting Jacob, his brother and his friend as they rode their bikes home. But she had the instincts of an investigator, scouring newspaper microfilm, interviewing suspects and looking up weather reports from that night.

Reading her blog, the Wetterlings were struck by the details she'd included — and the ones she hadn't.

"I found myself asking, over and over, who the hell was this woman?" Patty Wetterling recounts in the book.

For months, Wetterling and Baker talked by phone and email, trying to arrange a meeting. Then, in 2013, Baker reached out to Jared Scheierl, who as a 12-year-old was snatched from the street and assaulted in nearby Cold Spring, Minn., nine months before Jacob was taken. (Baker found him with genealogy skills and one key fact, reported in the press: Scheierl was kidnapped six days before his 13th birthday.) At first, Wetterling was protective of Scheierl. But she came to see that Baker was protective of him, too.

The Wetterlings and Scheierl had dinner at Baker's home in New London, Minn. Her husband, a turkey farmer, grilled cheeseburgers.

Wetterling noted the framed photos of Baker's children in the hallway.

"She's normal!" she thought, telling the story years later, in the same house. From across the kitchen, Baker laughed. That evening, she'd had the same thought. Here was this national figure, who'd shaped legislation, met presidents, appeared on TV. But she was also warm, self-deprecating, easygoing.

Quick to cry, but quick to laugh, too.

That night shifted things. As Baker uncovered a series of attacks in the late 1980s against boys in Paynesville, about 30 miles south of St. Joseph — where, it turned out, Heinrich had lived — she kept Wetterling in the loop. Wetterling had become frustrated with the Stearns County Sheriff's Office, which she believed had let the search stagnate.

"She calls herself 'Joy the Curious,' and that's perfect," Wetterling said. "... And that was a huge advantage, because we didn't have anybody who was curious about Jacob's case anymore."

'Now who are you?'

The crowd at the Oaks at Eagle Creek Golf Club in Willmar this past May was small, friendly. A group of Baker's fellow Rotarians, wearing buttons and shaking hands.

Still, Baker and Wetterling were nervous.

They'd both given speeches before. In Wetterling's case, hundreds. But this lunch was the first time they'd be talking publicly about their book, which suddenly had a title, a cover and a release date that was fast approaching.

Wetterling spoke tentatively, at first. But she warmed up when talking about Baker. "It wouldn't be a book without Joy's skill and ability to understand what I was trying to say."

Back when Wetterling first mentioned a memoir, Baker figured she'd be an organizer. A cheerleader, maybe.

She began in 2015 by sorting through grocery bags and litter boxes stuffed with mail that Patty and Jerry had refused to toss, in case they might contain a clue. She filed faded newspapers into waterproof bins. She paged through Jacob's school papers until she knew his handwriting.

Then, in the middle of it all, Heinrich was arrested.

"I remember going down and staring at those bins," Baker said, "and just kind of falling apart."

She and her husband stopped by the Wetterlings' home with chicken noodle soup and an artwork that she'd long had hanging in her office: "She knew the answers would come," it says, "with time and love."

After Jacob was found, "I had to take a year, almost two years off," Wetterling told the Willmar group. "Now who are you? People would see me and they would cry. It was so hard. I didn't go anywhere. I didn't go to the grocery store. I couldn't handle the sadness every day.

"I appreciated it, because you carry Jacob with you. I know that. But I was just lost."

They found their way back to the book in 2018. It could no longer help with the search. And it couldn't be the "thank you" Wetterling had once pictured, as "no one wants to read 50 pages of names." But maybe, she hoped, it could aid another parent in dealing with loss.

They wrote chronologically. Baker collected articles from the archives, forming a timeline of not only the investigation but Patty's national advocacy. She rebuilt Patty's old Macintosh computer, in order to extract its files.

Then, during the pandemic in 2020, they took a virtual writing class via the Madeline Island School for the Arts and realized: The book's structure was all wrong. On the wall of Baker's home office, they mapped out a new one with Post-it notes. Wetterling's youth, now told through flashbacks. The search, the psychics. The founding in 1990 of the Jacob Wetterling Foundation, which would become the Jacob Wetterling Resource Center, the passage of the Jacob Wetterling Act in 1994, the first federal law requiring states to keep registries of convicted sex offenders.

Then, a sticky note with two names: "Joy and Jared." Next to them, a smiley face.

There were several factors that led to Heinrich's arrest. Advances in DNA technology. The FBI's renewed look at the case. But Wetterling believes that Baker's work connecting the Scheierl's assault, the Paynesville attacks and Jacob's abduction was key.

After talking about the book, taking questions from the crowd and accepting a round of applause for her recent 50-year wedding anniversary, Wetterling returned to her table. The man beside her, Steve Rambow, had already shared a few connections: They had both been math teachers. His son wore No. 11 for sports, just like Jacob. Teaching in Paynesville, he remembered Heinrich as a student.

But after hearing Wetterling speak, he leaned in: "I lost a son, too."

"I'm so sorry," Wetterling said. She sat down, meeting him at eye level. "You carry him here, don't you?" She tapped her heart, near where she was wearing a pin with an 11.

Rambow nodded, wiping away tears from beneath his glasses. He told her that his son had died by suicide in 2006, when he was 16.

"At least I knew," he said. "You had to go 27 years. I can't imagine. I probably wouldn't be alive."

"You find strength you didn't know you have," she said.

They hugged, and Rambow hung on, as if drawing some strength from her.