Swedish immigrants Olaf and Caroline Freeburg — called Ole and Lena in the 1900 federal census — dressed up their four children one day and left their farm in current day Nowthen for the Anoka studio of fellow Swede Peter Nelson, who shot family portraits there and in other nearby towns.

Caroline came the closest of the six to smile for the camera, which sharply captured the seated couple surrounded by their four kids: Mary, Jack, Daniel and David — the latter two wearing fanciful neckerchiefs.

Fast forward 120 years to Tania Hansen, a retired delivery nurse in Boston who was pursuing her travel hobby of scouring antique shops for old family photos with identifiable subjects. She plucked the matted image of the Freeburgs from a bin in either Tecumseh, Mich., or Tiffin, Ohio, and added the image to her collection of 500 similar photos.

A Minneapolis native, Hansen said she loves to post her collected photos on genealogy websites to aid family members digging into their ancestry.

"Part of it is fun and games," she said. "But so many people don't know who their ancestors were or what they looked like, so I try to give a boost to family researchers."

Enter Kate Kelley, 45, a special-education teacher in Attleboro, Mass. Struck by all the unknown non-relatives she spotted while sorting through old family photos with her mother during the pandemic, Kelley also started collecting labeled pictures. But she took what she calls her "passion project" a step further.

Using genealogy and social media websites, Kelley launched the Photo Angel Project — actively tracking down descendants of family members in old photos and sending them the pictures. In the process, she has attracted national publicity and 22,000 followers on social media.

"When a case is closed, a once orphaned image returns to a loving home," NBC's Catie Beck reported for a story on Kelley last March on "Sunday Today."

Kelley told me she's reconnected "hundreds, maybe thousands" of photos with family descendants in 42 states and five countries. "I can't let them live in a dusty box in an antique store," she told Beck. "So they come home with me and I do my best to connect them with relatives."

She buys the photos herself and accepts donations, but basically provides the service for free. She told me she doesn't stalk family members randomly, but targets only those who are "active on genealogy sites, who have a vested interest in their family history."

"Preserve the past. You don't know who you are until you know who your ancestors are," Kelley said on "Sunday Today."

When Hansen got wind of Kelley's shared obsession for old photos, the two connected last summer in Boston. Kelley picked up boxes of labeled photos from Hansen, among them the Freeburg family photo. "My 800-square-foot place in Boston's North End had no more room for old photos," Hansen said.

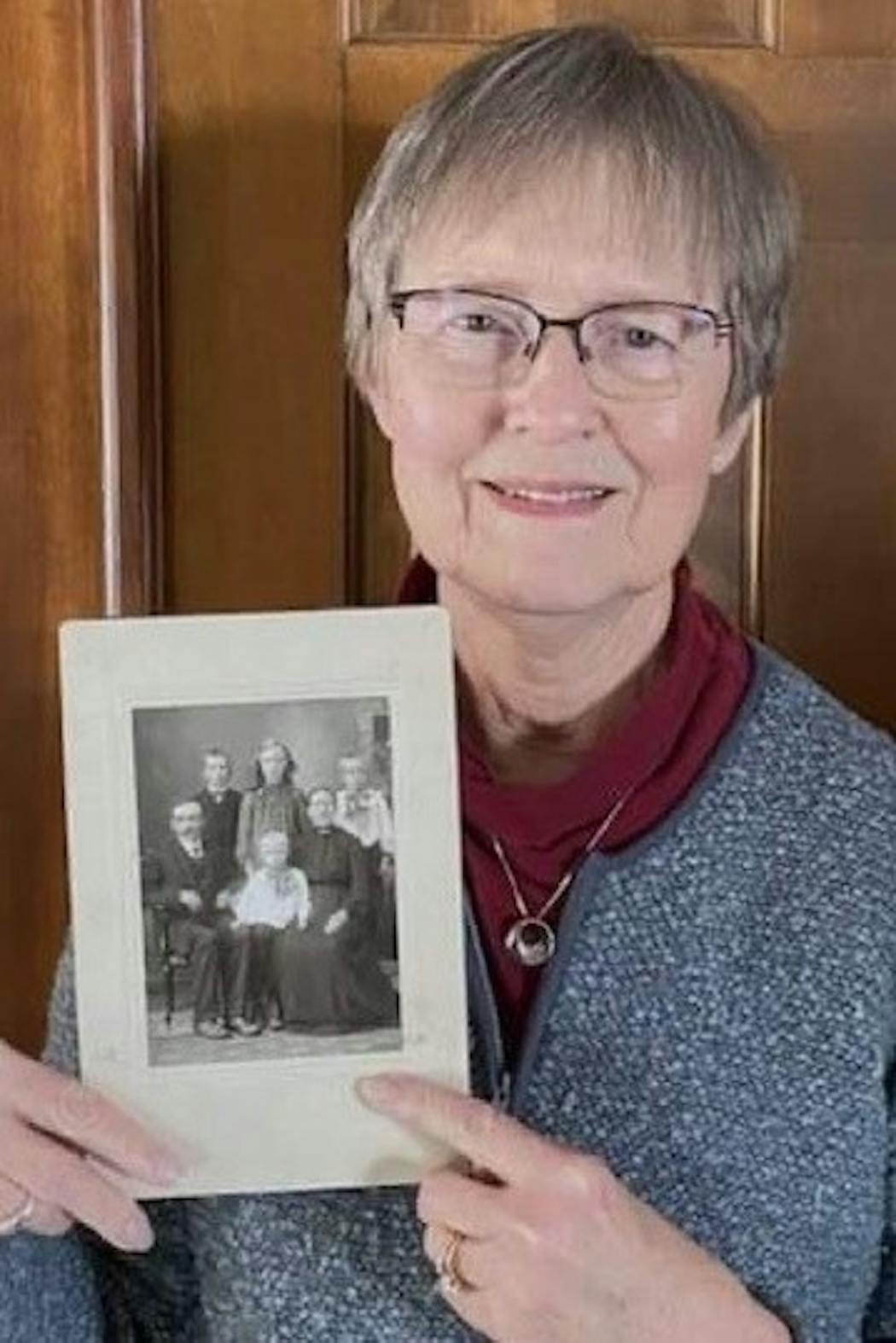

Here's where Joan Klaiber of Roseville comes in. She's the only child of David, the youngest kid in the Freeburg photo. Kelley tracked Klaiber down and sent her the picture after finding it in the Hansen stock.

"I can't figure out how the photo ended up in an antique shop in Ohio or Michigan, but I'm glad to have it," said Klaiber, 82. She already had a copy of the photo but is grateful to Kelley and Hansen for sending this one.

"It's a wonderful project,'' she said. "I wonder in 30 years whether anyone will get family photos taken or have interest in these old ones."

Klaiber's grandfather, Olaf Peterson, emigrated from Sweden in 1886 at 28; Caroline Stalberg came two years later. Sometime after they married, they changed the family name to Freeburg (which David eventually spelled Freeberg).

Klaiber guesses her father was probably 4 when the photographer's flash popped, which would make the year about 1904. David would spend his career as a warehouseman, according to the 1942 Minneapolis city directory, working for Red Owl for more than 25 years. He died at 92, in 1993 — but he's far from forgotten.

David Freeberg "was a stoic Scandinavian — understated and steadfast," said Paul Klaiber, 54, of Mahtomedi, who had his left arm tattooed with the Red Owl logo to honor his grandfather. "He was a hard worker who never complained and minded his own business."

Paul, who works in 3M's dental division, said he got the tattoo "as a tribute to a guy who left the farm in Nowthen and worked for more than 25 years in the Red Owl warehouse — back when employees had a commitment to their employers, and employers had a commitment to their workers."

Paul Klaiber worries that those days are gone for good — just like the era when family portraits, like that of the Freeburgs, were commonplace.

Curt Brown's tales about Minnesota's history appear every other Sunday. Readers can send him ideas and suggestions at mnhistory@startribune.com. His latest book looks at 1918 Minnesota, when flu, war and fires converged: strib.mn/MN1918.

Minnesota History: Ad man turned Paul Bunyan into a folklore icon

Minnesota History: James Griffin used persistence to blaze a trail for St. Paul's Black police officers

Minnesota History: For Granite Falls doctor who tested thousands of kids for TB, new recognition is long overdue

Minnesota History: A New Ulm baker wearing a blanket fell to friendly fire in the U.S.-Dakota War