Reducing the size of the Minneapolis Police Department lacks deep support among residents across the city, according to a new Star Tribune/MPR News/KARE 11 Minnesota Poll.

The poll found that only 40% of residents back this idea, while 44% of them oppose it. Others were undecided. Among Black residents in Minneapolis, opposition to cutting police officers reached 50%, while only 35% said they agree with such reductions.

But city residents overwhelmingly support shifting some police funding to social service programs, the poll found.

The findings are the first broad look at how the public views law enforcement in Minneapolis since the police killing of George Floyd in May, which swiftly prompted initiatives to overhaul the city's police department.

A City Council proposal to replace the department with a new entity was blocked from appearing on the November ballot earlier this month by the city's Charter Commission, which wants more time to study it.

Sam Brown, who is Black and lives in north Minneapolis, said he worries that fewer police officers would mean delayed responses to nonemergency 911 calls. He said he recently waited 45 minutes for an officer to arrive after being involved in a car accident, but no one came. If there is a robbery and no one was injured, he said, it could be a lengthy wait with a smaller force.

"It's going to take them longer to get there and by then the perpetrator is gone," said Brown, 59. But he added that he believes that officers need more training in identifying mental health and chemical dependency problems and de-escalating volatile situations.

Nearly half of those polled said they believe reducing the size of the police force would have a negative effect on public safety. Roughly a quarter thought it would have a positive effect, with the remainder saying they were not sure or that it would have no effect. Half of respondents said they feel crime has increased in the last few years.

The poll was conducted for the news organizations by Mason-Dixon Polling & Strategy, Inc., which surveyed 800 registered Minneapolis voters earlier last week, including 146 Black voters. In addition, 354 more interviews were conducted with Black registered voters in the city, for a total of 500. The margin of sampling error is 3.5% for the sample of 800 registered Minneapolis voters, and the margin of error for the sample of 500 Black Minneapolis registered voters is no more than 4.5 percentage points.

Oluchi Omeoga, a co-founder of Black Visions Collective, a community group that has pushed for the charter amendment, said the poll findings show an overwhelming desire among city residents to rely less on the police. The results were more muddled regarding reducing the force, the group contends, because there is currently no alternative to call for lower-level incidents.

"When we're talking about mental health services and someone is having a mental health crisis, the first thing that we know to do is to call the police," said Omeoga, who is Black. "So what does it look like for us to invest in other services to that we are being less reliant on people who aren't keeping us safe?"

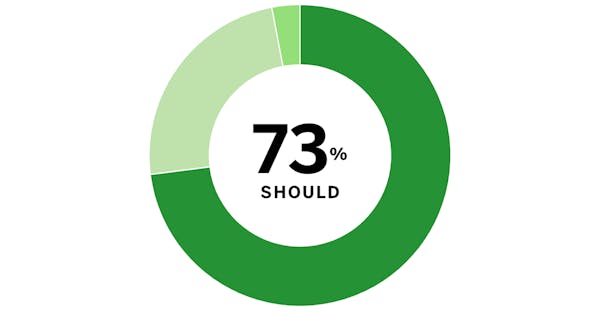

Opinions were much less mixed about redirecting police funding. Nearly three quarters of those surveyed favored shifting some funds from the police department to social services like mental health, drug treatment and violence prevention programs. That idea was most supported by younger residents and DFLers, and had far less support among people over 65 and Republicans.

"By investing in communities ... with education, with youth services, with homeownership, with employment, you wouldn't need as many police," said Aaliyah Hodge, who is Black and lives in north Minneapolis.

Hodge, 25, said she initially reacted skeptically to calls to defund the police. But after further thought, she sees benefit in other approaches.

"[People] commit crimes because there's a scarcity of resources, because there are no additional options for you, and because of systems of historic racism when you think about homeownership, jobs and employment and educational prospects," Hodge said.

It may prove challenging for city leaders to redirect funding without reducing the size of the police force. The Minneapolis police department is authorized to have 880 officers — though it has been operating below that level — and more than three-quarters of its budget pays for salaries, wages and fringe benefits.

"At the margins you can do some things, but fundamentally if you're talking big dollars it's an 'either or,' " said Steve Cramer, president of the Downtown Council, a group that promotes economic development in downtown Minneapolis. "So I think that's the dilemma."

Cramer, who is white, said his organization supports "complementary" public safety initiatives like mental health services that are not performed by sworn police officers. But it does not support a smaller police force.

"Where do the dollars come from and how much can you cut back on law enforcement without impeding things that they do really need to do in an effective way?" Cramer said.

Dr. Erica Levine, a poll respondent who is white and lives in northeast Minneapolis, said if city residents could summon people who are experienced in mental health and de-escalation tactics, it may reduce the need for officers.

Recently she called 911 to assist a man who appeared to be suffering from mental health problems at a coffee shop near the University of Minnesota. But she was unnerved by the dispatcher's line of questioning, intensely probing whether the man was a threat.

"It seemed like they were trying to figure out a way to turn this 911 call into a way to justify having a little bit more force with this gentleman," Levine said. "Other friends that I've had that are also in the medical field have had similar experiences trying to get help for people in the community."

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?