He liked it because it didn't have seats but still felt big and theatrical. He liked it because it was a rock club that didn't just book white rock 'n' roll acts. He liked it because the staff would let him show up anytime he wanted, including surprise gigs on short notice. And he liked it for the same reason so many musicians before and after him did and do: It's just a great live-music room.

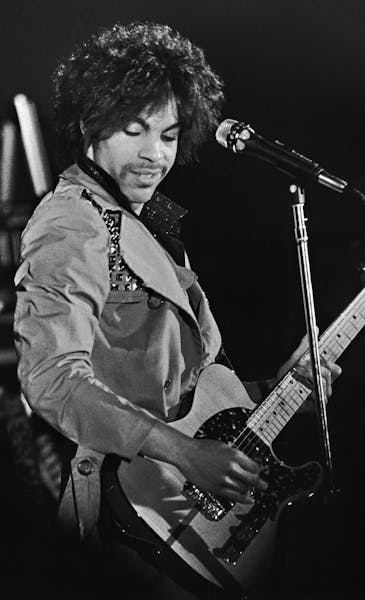

Paisley Park will forever be known as the place where Prince resided and died, but First Avenue is truly where Minneapolis' newly deceased rock icon came to life.

The boxy, pristine, white studio and residence in suburban Chanhassen would make a good place for a museum, as family members have hinted could happen. The curvy, rugged, black club in downtown Minneapolis, however, is still a living, breathing, thriving testament to his legacy and might ultimately be the best place to remember Prince on his home turf.

"Playing there was always important," said Prince & the Revolution drummer Bobby Z in a recent interview before the April 21 death of his old boss and friend. "It became his marquee, and it still is today."

That First Avenue and Prince would forever be tied at the hip was reiterated in the days and even just the hours after his passing.

Media outlets worldwide showed images from inside and outside the club as 10,000-plus fans lined up for an impromptu street party on the night of his death, and then for the subsequent three-night, all-night, sold-out dance parties. Headlines included this one from CNN: "Fans remember Prince at iconic club."

Of course, that wasn't the first time TV crews and magazine reporters flooded the venue looking for All Things Prince.

In the months after "Purple Rain" came out in July 1984 — featuring performance scenes filmed at the club over three frigid weeks the previous winter, plus songs recorded live on a hot August night — media outlets were on-site filing Prince stories on a weekly basis. Fans from around the world kept coming even after the media left, making it Minnesota's No. 1 tourist destination for several years in the mid-'80s.

The influx of revenue that Princemania brought to First Avenue came at a pivotal time, remembered Allan Fingerhut, who used almost $200,000 of his family's catalog-sales fortune to convert the former Greyhound bus depot into Minneapolis' largest club in 1970. It was first named the Depot, then Uncle Sam's, and was briefly just Sam's when Prince played his first show there on March 9, 1981.

Today, First Ave is one of America's most successful, long-lived and well-known independent rock clubs. Rolling Stone readers ranked it No. 2 in 2013, and touring musicians ranked it No. 1 in a 2011 Metromix poll. The club might not be here today if not for Prince.

"I don't know if we could've kept the place going the way it was losing money" in the mid-'80s, Fingerhut said. "He saved the place."

Retired in California since losing the club in a 2004 ownership battle, Fingerhut laughed last week about how often Prince was mistaken as the club's owner in those days: "I was fine with that. In a way, he did own it."

The guy who first brought in Prince to perform was the club's longtime talent booker and manager, Steve McClellan. Also a champion of African and Caribbean music acts at the club during that time, McClellan marveled, "It was so exciting in the early '80s to see Prince mix the audiences, the racial diversity he brought in. I had never seen that before to that level."

However, McClellan said the "Purple Rain" effect had its downside on the club's ongoing effort to promote new and left-of-center bands.

"The crowds didn't care who was on stage," he said. "They only cared about whether or not Prince was coming in that night."

That wasn't always the case, though. There was one night in May 1983 when Prince did show up to see Jah Wobble — bassist in John Lydon's Public Image Limited.

"Prince wanted to get on stage, but Jah Wobble didn't even know who he was," McClellan recalled. "And the crowd wasn't very excited Prince showed up, because those 300 people were all the Sex Pistols/PiL audience."

'Mutual acceptance'

Prince had enough of an audience and buzz in March 1981 to pack the place his first time there. His previous hometown show at the Orpheum Theatre a year earlier only drew a half-full crowd. But McClellan heard very good things about the show via two of the downtown record-store clerks he often turned to for recommendations: Kevin Cole, who also DJ'ed dance nights at Sam's; and Jimmy Harris, who would soon be better known as Jimmy Jam of the Time.

Cole, now program director at KEXP in Seattle, still talks about the March '81 show like an epiphany moment for both the club and the budding rock star.

"It was one of the greatest shows I'd ever seen, not just great music but that way Prince connected with the audience," he said. "There was a mutual acceptance, like, 'Wow, these are my people.' "

Prince's childhood friend and bassist at the time, André Cymone, recalled a similar connection.

"I remember it was just an unbelievable performance," he said. "There was a good-to-be-home side to it, but also a little bit of the conquering-hero thing."

The site of legendary concerts in the 1970s by Joe Cocker, Ike & Tina and B.B. King, the club that would become First Avenue mostly hosted dance nights during the mid- and late-'70s disco heyday when the teen wunderkind first started crashing local stages. That all changed at the end of 1979, when the Uncle Sam's name and management was out and Fingerhut put McClellan in charge.

"Everybody was talking about" the newly revitalized club, Cymone recalled. "It had a buzz. It was an edgy venue. We wanted to be edgy and push the envelope a little bit."

The 1981 gigs came amid a long two-year touring cycle that included a trek as Rick James' opening act and European dates. Bobby Z remembered playing European venues such as the Paradiso in Amsterdam and "these First Avenue-type places that had an open feel: gutted theaters, churches, really cool open spaces that really, really opened up." Prince liked the openness.

"It was like there couldn't be any two more perfect collisions than Prince going out, seeing the world, experiencing these other venues, and then coming back and finding we had one right here."

The collision that sparked a world phenomenon happened at the club on an especially sweaty summer night, Aug. 3, 1983. Under the guise of a fundraiser concert for Minnesota Dance Theatre — which was helping him and the band on choreography for an unspecified movie project — Prince brought a recording truck to the club, helmed by Bobby's producer brother, David Z. He debuted a new guitarist, Wendy Melvoin, and a batch of new songs, including the opener "Let's Go Crazy," "I Would Die 4 U" and "Computer Blue."

For his penultimate song, Prince unveiled a new ballad called "Purple Rain" that would last 11 minutes that night.

Fans in attendance seemed to understand it was a landmark moment. Though who would have guessed the singer would whittle the song down to four minutes, take out the audience and clean up the audio but otherwise leave the song as-is on the album of the same name that came out the next summer?

"When he hits those guitar solos on 'Purple Rain,' they were real!" Bobby Z said. "And they're captured for real. Nobody ever did anything like that before."

The Prince Permit

Things got even more incredible a year later when Prince's people approached First Ave's operators about booking the club for a monthlong movie shoot. While they could have easily shot live performances at a sound stage in Los Angeles — and did so for backstage shots rather than use the club's puny dressing room — the club proved integral to the movie.

"There was never any doubt that the music [performances] would be at First Avenue, as far as I know," said Bobby Z, addressing the popular notion that the club deserved a co-starring credit in the movie. "The story is about Prince, Apollonia, Morris Day and First Avenue. By using this club as some sort of mythical land where bands became famous ... Prince made the club famous."

And he, in turn, became one of the most famous musicians in the world. Prince only came back to perform at First Ave two more times in the '80s — to warm up for the "Parade" and "Sign o' the Times" tours in March 1986 and March 1987, respectively. By the time of the latter show, construction had begun on Paisley Park, which became his playhouse for unannounced hometown gigs in the ensuing years.

When he finally returned to the First Ave stage one last time in 2007 — 7/7/07 — it was classic Prince, in the good and bad sense.

The show was a loose, lively performance of some of the funkiest songs in his discography, but the star was too loose with the clock. It was the third of three concerts he lined up that day in downtown Minneapolis, including a promotion for his new perfume at Macy's and then a full-scale Target Center set. He didn't take the stage at First Ave until about 2:45 a.m.

Police let him play for just over an hour but then shut it down.

"It was understandable, but heartbreaking," said Dayna Frank, who now owns First Ave along with her dad, Byron Frank, Allan Fingerhut's longtime accountant.

After that 2007 letdown, the club worked with city staff and Mayor R.T. Rybak on a plan to allow for a later closing time should Minneapolis' most famous native son come calling again. The outcome was a special-use, after-hours contract known simply as the Prince Permit.

Sadly, the namesake of that special plan would never get to use it, but the club did. First Ave thought Prince would have approved of fans mourning him together in the close, familiar confines of that one, electric room for an all-night dance party. Even better: three all-night dance parties.

"After the initial shock and grief of his death, the first thing we said was, 'We gotta pull the Prince Permit!' " Dayna Frank said. "And the city, to its credit, complied right away. For nobody else but Prince could this happen."

And probably for no other nightclub.

Chris Riemenschneider • 612-673-4658

@ChrisRstrib

The 5 best things our food writers ate this week

A Minnesota field guide to snow shovels: Which one's best?

Summer Camp Guide: Find your best ones here

Lowertown St. Paul losing another restaurant as Dark Horse announces closing