They're calling his actions "bold" and "brilliant" now, but it wasn't so long ago that Ramsey County Attorney John Choi was roundly criticized for not being tough enough on the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

In fact, when Choi announced in late 2014 and early 2015 that his office wouldn't file charges in nine cases of alleged clergy sex abuse because the statute of limitations had expired, and for lack of evidence and other complications, his critics pounced. One went so far to say that Choi was no "profile in courage."

So when Choi's office laid out its dual-pronged strategy June 5 of filing criminal and civil charges against the archdiocese for its handling of child sex abuse cases, critics and supporters, some of whom heralded the effort as "unprecedented" and "transformational," were stunned. Yet to those who know him best, it was no real surprise. The way it quietly came together was hallmark Choi — subtle, straightforward and by-the-book.

"I just felt really terrible how John endured some criticism, yet, in the end, he found the perfect way to deal with this factious issue," said Washington County Attorney Pete Orput. "I think it was brilliant and courageous on his part. I think he went back — looked at it in a more macro view.

"This is the John I know."

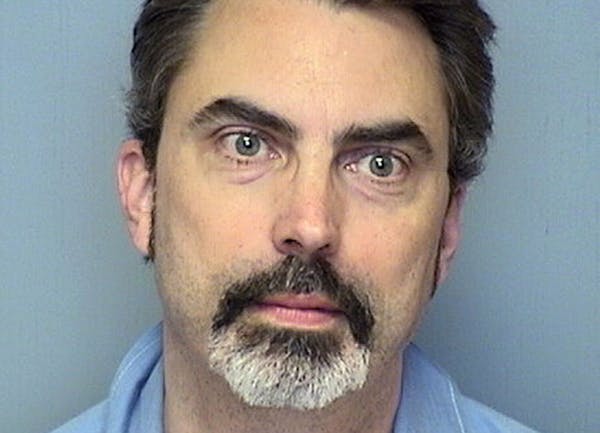

Choi, 45, charged the archdiocese with six gross misdemeanors for allegedly "failing to protect children" against former priest Curtis Wehmeyer, now in prison for abusing two boys.

But since a corporation cannot be jailed or imprisoned, any convictions on the criminal charges would likely result only in fines — a maximum of $3,000 for each count. That's why some feel that the civil action is the clincher in Choi's strategy.

The civil petition alleges that the archdiocese "by act, word or omission encouraged, caused or contributed" to the need for services or protection of three sex abuse victims.

Choi's office is asking that a judge hold the church accountable to the law and require it to participate in "evaluation as determined necessary by the Court to correct and eliminate the conditions that contributed to a child's and children's need for services or protection." It also is asking that it be required to "demonstrate to the Court's satisfaction over a reasonable period of time compliance with the Court's orders," and "other and further relief as the Court deems just and equitable."

If a judge agrees, the strategy would result in court oversight of church actions, unlike a landmark 2014 settlement between the archdiocese and attorney Jeff Anderson that laid out a 17-point "child protection plan."

Anderson, who has sued the archdiocese several times on behalf of abuse victims, said it "adds another dimension of power and heft that can be held over [the archdiocese]. So, to me, that may be the most meaningful part of this process … because imposing fines against a few people doesn't really change anything."

Joseph Daly, professor emeritus at the Hamline University School of Law, said there could be some First Amendment conflicts to navigate, but that the tactic was necessary and "unprecedented."

"That's civil authority from a judge and the county attorney getting deep, deep, deep into how the archdiocese is run," Daly said. "To me, that's pretty powerful stuff."

'Facts will lead the way'

Choi declined to comment for this article, citing the pending cases and ongoing investigations.

That's no surprise. When critics attacked in the past, Choi was unflappable. He didn't try to quell public pressure by expressing his confidence in the 20-month-long investigation that eventually led to the June 5 filings.

He spoke in generalities and held his cards close to his vest, as has been his practice for all pending cases, big or small.

"As we have said from the very beginning, the facts will lead the way," he said in a written statement in February, when his office declined to charge two cases of alleged priest sex abuse.

"We can only do what the law allows, and we will do what justice requires."

Praise from colleagues sympathetic to the pressures of public office may be easy to come by. But even Choi's fiercest critics, some of whom wondered whether he was reluctant to charge because of his St. Paul roots and church ties (he was raised Catholic), have been forced to acknowledge a change of heart.

"I was growing increasingly concerned that no action would be taken," said Anderson, who frequently challenged Choi's decisions. "When I saw that it was charged, my view changed. I thought it was creative, that it was bold and necessary, and that it was obvious that they worked hard on it."

Anderson, who has played an important role in the investigation by turning over tens of thousands of pages of church documents to Choi's office, called Choi the day of the filings to praise his staff.

When the church sex abuse scandal erupted in 2013 with the public disclosure of documents by its former canon lawyer, Jennifer Haselberger, Anderson served as a counterpoint to Choi.

Charismatic and ubiquitous, Anderson shined in his campaigns to bring the church to court. He made dramatic headway into his investigations, obtaining depositions from Archbishop John Nienstedt and former Vicar General Kevin McDonough.

'He didn't grandstand'

By comparison, Choi's understated approach inspired little faith among the public and abuse survivors. Yet his team of investigators, among the best in his office, worked with St. Paul police to interview more than 50 witnesses and review more than 170,000 pages of documents.

Choi was legally bound to limit what he could reveal about the investigation, but he also chose to remain quiet.

"He didn't grandstand," Orput said. "I don't know if I could have been that reticent."

For those who know Choi, it wasn't a sign that he had dropped the ball, but rather that he was protecting the integrity of the case.

"I think he handled the public pressure the way an official in his position should," said Hamline Law Prof. Ed Butterfoss, who taught Choi at Hamline. "He took a thoughtful approach, not a knee-jerk reaction to what people were demanding."

Butterfoss recalled Choi as a "quiet student." Diligent and competent, he didn't necessarily stand out.

But as Choi rose through the ranks of partner at Kennedy & Graven to St. Paul city attorney in 2006 at age 35, to Ramsey County attorney in 2011, Butterfoss grew to know him as someone who was "about solving big policy issues and effective solutions as opposed to just, 'I'm going to put people in jail.' "

Under Choi's leadership as city attorney, St. Paul in 2009 became the state's first city to use an injunction to ban gang activity at a community festival.

As county attorney, he initiated the East Metro Crime Prevention Coalition, an effort among Ramsey, Dakota and Washington counties to bring stakeholders together for daylong trainings on issues such as bullying, prescription drug abuse and fraud.

Frank Meuers, a Minnesota member of the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests (SNAP) who had previously questioned Choi's courage, admits he's changed his mind. Still, he wants Choi to know that public scrutiny won't go away anytime soon.

"We just ask him to be diligent," Meuers said. "We'll be watching."

Chao Xiong • 612-270-4708

Twitter: @ChaoStrib

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?