How a Lake Street shopping center is rebuilding after riots

At the corner of Lake Street and Nicollet Avenue in Minneapolis, workers are erasing the scars left by one of the most turbulent weeks in Minnesota history.

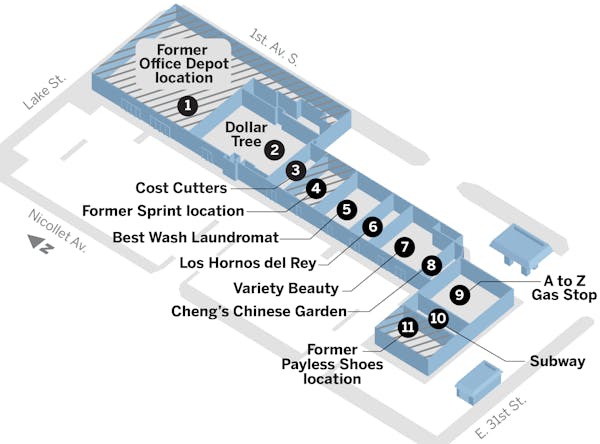

A contractor sands the new facade that hangs over a Subway restaurant owned by a Cambodian immigrant. A few doors down, electricians are hooking up laundry machines at Best Wash, owned by a Chinese native. Another crew is hanging wallboard at the Mexican bakery.

Highland Plaza Shopping Center has buzzed with activity since August, when its owner decided that waiting to rebuild was the worst thing he could do for his tenants, most of whom came to America for a fresh start.

This blocklong strip center, situated between the old Kmart and the Police Department's Fifth Precinct station, is one of more than 1,200 commercial properties ransacked or destroyed in Minneapolis and St. Paul during the riots that followed the death of George Floyd in May. Several tenants at Highland Plaza plan to usher in the new year by flinging open their newly installed glass doors in as little as two weeks.

"It takes a lot of trust to go through this," said Gina Ahn, whose Korea-born parents bought the Variety Beauty store at Highland Plaza just a few months before it was looted. "But our landlord really stepped up."

Many landlords have done little or nothing with their riot-damaged Lake Street properties, leaving large parts of this once-thriving thoroughfare devoid of activity.

Some merchants have been left homeless after their landlords evicted them, sold out or chose not to rebuild. Other Lake Street tenants have closed permanently instead of trying to rebuild during a pandemic that is crushing the economy.

Tom Roberts, longtime owner of Highland Plaza, thought about giving up. He has always nursed dreams of selling the center to a condo or apartment developer, and he wondered if this was the right time to let someone else take over.

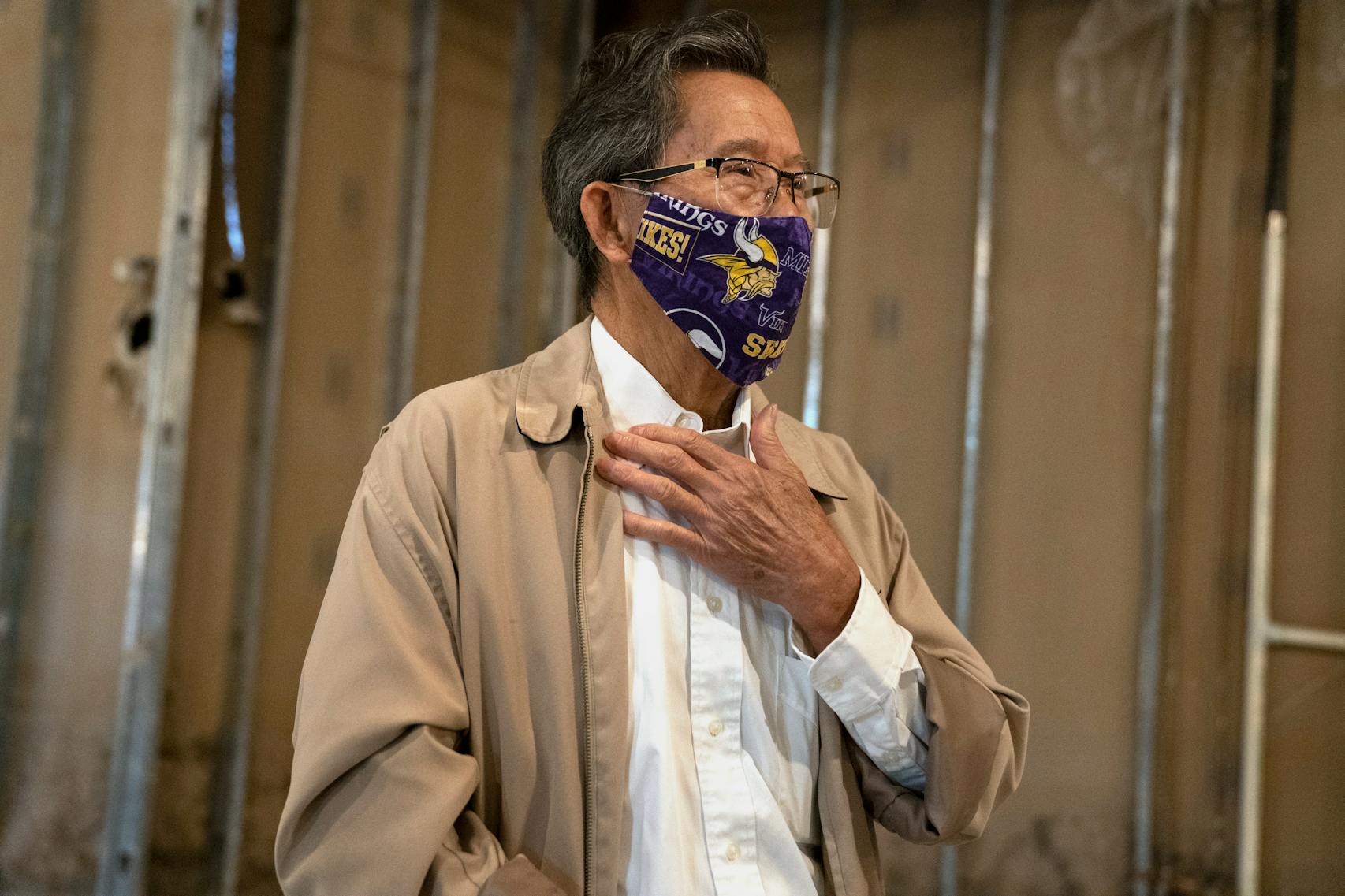

But Roberts couldn't walk away from the immigrant business owners who occupy most of his mall. He has known some of these entrepreneurs for more than 20 years. A few were so poor when they started out that they slept in their shops after a long day's work. Roberts has helped them solve tax problems, lent them money, watched some become wealthy and even attended their weddings.

"I am personally connected with a lot of these families," said Roberts, who turned 69 in November. "I felt an obligation to rebuild and help them out."

The struggles involving the rebirth of Highland Plaza are playing out across the Twin Cities, as landlords wrestle with when, or whether, to rebuild. Property owners say fears of more civil unrest are scaring away potential tenants and even some construction workers.

For Roberts, the road to recovery has been challenging. Two of his tenants — Office Depot and Sprint — abandoned their spaces after the riots, even though their leases still run for more than two years. Finding new tenants has been difficult.

Communication is also a struggle. Some of Roberts' tenants — who immigrated from six countries — come to site meetings with interpreters to help them understand the complex rebuilding decisions they must make. One tenant doesn't own a computer.

Insurance carriers have been slow to pay. Though Roberts has no complaints about his insurer, some of his tenants have waited so long to get claims paid they're not sure they'll reopen. Some will have to draw heavily from their savings to cover the bills.

Despite daunting obstacles, all seven of Highland's immigrant business owners want to reopen. Some are reinvesting to make sure a second generation will have a business to run.

"It is a good opportunity for a younger generation of my family," said Kim Seng, 75, whose nephew will be taking over his Subway franchise at Highland Plaza. "It may not be so good in 2021, but it will be good in 2022 and 2023."

The toll of the riots

The first rioters arrived at Highland Plaza on May 28, three days after George Floyd was killed while being arrested by Minneapolis police.

It was shortly after 2 a.m. when a car pulled up outside the A to Z Gas Stop. Four men broke into the convenience store, loaded the back seat of a car with stolen merchandise and took off five minutes later when the police arrived, security footage shows. Other looters returned within an hour, but once again, the police showed up and made arrests.

That was the last time police stopped anybody from looting the shopping center.

Joe Zerka, whose father opened A to Z in 1997 after moving to Minnesota from Lebanon, was at Menards a few hours after the break-in. He filled his pickup with $1,000 worth of plywood to board up his store and other family properties. Other Highland merchants quickly followed suit. But the barriers did little to deter rioters, who used sledgehammers to bust their way into Highland stores on May 29.

"We marched peacefully forever," shouted one protester, according to video footage of the riots. "And now what? You are getting what you deserve."

Some Highland merchants put up a fight. At the Best Wash, two employees stayed behind to fend off rioters by shouting at them through the plywood. Nobody made it inside, though the business was damaged by fires that broke out in adjacent spaces.

Ahn knew it was a losing battle. The crowds were too big, too out of control. Earlier in the week, Ahn and her father were overwhelmed when they tried keeping rioters out of their 7 Mile Fashion store at Hi-Lake Shopping Center, 2 miles away. Her father was hit in the head with a fire extinguisher when he blocked the door. A woman pointed a gun at one of her employees.

Roberts was watching the violence unfold on television that Friday night from his home in Eden Prairie when he decided to make his stand.

"I said, 'This is nuts. Where are the cops and the National Guard? I am going down there,' " Roberts recalled.

Roberts drove to the shopping center in his Cadillac Escalade, forcing his way through hundreds of angry people. Then he spotted a reporter from KARE-11, who put him on live TV.

"What I want to tell people right now is that if the governor and the mayor are not going to take care of this problem, people will," Roberts said, as the crowd surrounding him cheered. "People will uprise over this. … People make their business here. They are Korean. They are Black people. They are immigrants. They have worked their [expletive] lives off trying to make this thing happen."

The National Guard was on the streets a few hours later, but it was too late for Highland Plaza. By Saturday morning, rioters had set fires in six stores. Other Highland merchants were inundated with smoke and water from the sprinklers, which ran for 20 hours.

Although all of the immigrant tenants expressed outrage at Floyd's treatment by the police, some said they also feel betrayed by the neighborhood.

"Seeing my store burning — that almost broke me," said Ahn, whose family lost three of its four stores to the riots. "I thought we were part of the community. We've seen people grow up. So it was very hurtful at first."

The rebuilding begins

In September, three months after the fires at Highland Plaza were put out, the smell of smoke is still so strong that visitors have to change their clothes after walking inside one of the gutted stores.

For weeks, powerful air scrubbers have been recirculating the air through filters to remove soot and mold. As Roberts walks past one of the circular vents, the wind blows the baseball cap off his head. It will take four months and cost more than $300,000 to finish cleaning the property.

Though he owns four other strip malls and has been doing real estate deals for more than 40 years, Roberts has never undertaken a project of this magnitude. Initially, he underestimated the damage. Although he knew he couldn't reopen in June, as some tenants hoped, Roberts figured he could get a few stores ready before Thanksgiving.

Nothing comes easy on a rebuild like this, said Diane Leverentz, a project manager with Classic Construction, the contractor in charge of the $5 million project.

"It's always easier to level it and start over," Leverentz said. "The unforeseens on a job like this are insane."

By reusing parts of the shopping center, Roberts will save about $4 million in construction costs. Even at that price, Roberts said, he will still come close to maxing out his insurance policy.

Money is a constant concern. At weekly site visits, Roberts pores over invoices that he has covered with red ink, questioning charges for as little as $186. He is a demanding boss, and his contractors quickly grow wary of his sharp tongue.

In October, he hollers when he discovers that Classic mistakenly put in an extra stoop he didn't approve.

"I'm not going to pay for it," he tells Leverentz. "How many times have we gone over this?"

Leverentz and her partner on the job, Corbett Larson, said they wake up every night worrying about Highland. Leverentz now keeps a notebook by her bed to jot down her thoughts so she can go back to sleep. Larson said he wouldn't have taken the Highland project if he knew what he was in for.

Roberts agreed he can be a tough client. "Once in a while I get a little more upset than I need to get," he said. "But I get over it very quickly."

Moldy shelving

Although many of his merchants struggle with English, Roberts doesn't have trouble communicating with anybody except his biggest returning tenant, Dollar Tree.

Roberts has been sending Dollar Tree regular progress reports, including photos, but he wonders if anybody is looking at them. In October, days before the company was scheduled to take back its space, Roberts receives a "punch list" of work Dollar Tree wants done. Among the chores: remove rotten merchandise from freezers and coolers. Roberts' team did that months ago.

On Oct. 27, the company sends district manager Justin Olsen to the site. Roberts begins griping as soon as Olsen walks into his empty store, now sanitized and gleaming like new construction.

"We've had some confusion," Roberts says, pointing to the punch list, which he calls a "joke."

Olsen agrees the requests are "ludicrous."

"In defense of the company, we probably have 60 or 70 stores that were exposed to civil unrest this year," Olsen says, adding that Dollar Tree has been overwhelmed by the work needed to reopen them.

After touring the rebuilt store, Olsen tells Roberts his bosses in Virginia "are very pleased at how fast and easy this has been."

Two days later, Dollar Tree sends a Canadian contractor, Roy Dominique, to the site. Dominique, who will install all of the merchandise racks, brags that he was able to finish another Dollar Tree store in nine days.

In that case, though, everything was new and sitting in the store when he showed up. At Highland Plaza, he's been asked to reuse the original equipment. Dominique heads to the parking lot, where the shelves have been sitting in 30-foot storage containers for five months.

As Dominique cracks the first door open, the smell of mold billows out. He spots green patches on the peg boards and soot and burn marks on the shelves. "It's salvageable, but it would take a lot of work," he says. "And I don't have the time."

The company, he says, will have to replace everything.

Wrangling with insurers

As the contractors rip up cracked cement and cut out moldy wallboard, one of the thorniest questions is who pays for what.

Roberts is on the hook for most of the work, but tenants are responsible for certain costs. Everybody has insurance, but the money is slow in coming and some tenants were woefully underinsured.

Daniel and Sara Ahn will pull about $1 million out of savings to rebuild their three 7 Mile Fashion stores. "That is supposed to be their retirement money," said their daughter, Gina, noting her parents are both 65.

Roberts is most worried about Cost Cutters and Cheng's Chinese Garden, which are scheduled to reopen in mid-January. Both are insured through State Farm, but their cases were assigned to separate adjusters. Roberts is livid when he hears that one adjuster signed off on covering $3,000 in flooring at the Chinese restaurant, while the other adjuster won't pay for new floors at Cost Cutters.

In late October, Leverentz calls the State Farm adjuster handling the Cost Cutters claim.

Besides objecting to the floors, the adjuster now wants to know why the bottom 4 feet of wallboard was removed in the store.

Leverentz explains that ServiceMaster, which was hired to clean the center, recommended removing that much wallboard in every space because it turned moldy over the summer.

"Mold is excluded from this policy," the adjuster says.

Roberts explodes. None of the other tenants, he says, are getting such denials, even though they all suffered the same type of damage.

"If I can't get her to reverse her decision, I won't let any of my tenants use State Farm," Roberts says.

City inspectors are flexible

From the start of construction, one of Roberts' biggest concerns has been how the city of Minneapolis would treat his project. Inspectors must sign off on the plans for every space, but the center was built more than 30 years ago and building codes have changed significantly.

As Roberts steps into Cheng's, he notes that the bathroom — located at the rear of the restaurant — will never pass muster under the Americans With Disabilities Act. For starters, there is no public access. Moving the restroom to the front could add $50,000 in project costs, busting the owner's rebuilding budget. It would also wipe out the tiny dining room.

The situation becomes urgent at the end of November, a few days before the inspector assigned to Highland is scheduled to retire.

Roberts asks Leverentz to call him immediately. "You can argue that it makes the restaurant impossible to rebuild," Roberts says.

To everyone's surprise, the inspector agrees to waive ADA requirements for everyone at the center, allowing them to rebuild their bathrooms the way they were before.

Steve Poor, the city's director of development services, said he instructed inspectors to be flexible on riot-related rebuilding projects.

"If people are just trying to get back to what they had, we try to work with them," Poor said in a recent interview.

Nearing completion

In December, as contractors rush to finish work on the first five stores to reopen, Highland Plaza begins to look more like a shopping center than a fortress. Plywood is replaced with glass. The security fence is moved to provide the first public access in months.

The biggest news arrives Dec. 1, when Roberts tells his construction chiefs that Walgreens signed a contract to move a mobile pharmacy into the parking lot. The company also is close to leasing a big chunk of the former Office Depot. The deal was made possible when Walgreens was evicted from a nearby property destroyed in the riots.

Though Walgreens hoped to open the mobile pharmacy in December, the company didn't deliver its trailer in time to make that deadline. Originally, Dollar Tree planned to open in December, too. But Dominque said the company took more than a month to send him all of the equipment he needed. He was also delayed when his assistant came down with COVID-19.

By mid-December, the virus has swept the job site. Two construction workers were hospitalized, and Roberts and several others are forced to stay away from the site for two weeks after they get sick. Masks, barely worn before now, become standard issue at weekly project meetings.

As he tours the center this month with Leverentz, Roberts finds out that the outlook for Cheng's is once again cloudy. State Farm has changed adjusters, and the new person is restarting the process for the restaurant's claim.

Restaurant owner Chun Chen is flabbergasted. "Omigod," she tells Leverentz. To reopen on time, Cheng's must immediately order $30,000 in new equipment. Roberts later tells Leverentz to place the order without waiting for State Farm's decision.

"Either the insurer is going to pay for it or I am," Roberts says. "We'll get them open."

One day after the Star Tribune provided a summary of Roberts' complaints, State Farm agreed to pay for the equipment and all requested construction costs for Cheng's.

Though Roberts is "95% sure" that several stores will reopen by Feb. 1, his tenants aren't as confident. The Ahn family hoped to reopen their 7 Mile Fashion store in north Minneapolis Dec. 1, but late-arriving merchandise, a faulty security system and other problems forced them to bump that date back four times.

The store finally opened Dec. 18. Despite a lack of advertising or even a "grand opening" banner, a steady stream of customers found their way back, generating 124 sales by day's end.

"We missed you," said Tracy Williams, who drove over from St. Paul to pick up $10 worth of hard-to-find hair products. "You have everything I need."

Staff writer Maya Rao contributed to this report. jeff.meitrodt@startribune.com • 612-673-4132