"Thanks for calling."

That was the free-writing prompt that opened a recent meeting of the writing group at the Waters senior residence in Edina. The eight members of the group plus its leader, seated around two pushed-together tables in the building's library, spent the next six minutes quietly scribbling individual mini-essays around that phrase.

Then they took turns sharing what they'd written: reminiscences about spam calls, calls from relatives, an eagerly awaited follow-up call from a boy (later husband) after a promising long-ago first date.

Adrine Nelson mused about calls from telemarketers. "I used to be a polite person before the telemarketers got to me ... my heretofore polite demeanor went the way of the unicorn. ... Then I started just hanging up. Lately I've been swearing before I do so."

That was just the icebreaker for the Waters writing group, which has been getting together at least once a month since 2016 (minus the COVID years). Their meetings follow an established schedule, and members are used to the drill: First they do the warmup writing, then they go around the table reading longer pieces they've written over the previous month.

All of the group's members in attendance that day except one — the daughter of a member — were in their 70s or older, and all were women (though a couple of men have participated in the past).

Novelist Kathleen Novak is the group's volunteer leader. A former English teacher and corporate communications writer, Novak became involved when her father was a resident of the Waters and she visited him every day. After her father died, she stayed with the group.

"It's a nice way to spend a couple of hours," Novak said. "Nice relationships come out of it, great stories. I learn things."

Levels of experience among members vary widely, from Nelson's "this is the first time I've ever attempted creative writing," to Mary Ann Hansen's, "I've been writing stuff since I was 11 years old. I've written two romantic novels." Hansen used to jot down ideas while making dinner, she said.

"I think the more we write, the easier it becomes; it just flows more easily," said Anne Franco. "I remember learning, 'Write what you know.' That's the easiest way to start."

Members develop writing styles that suit them, Novak said: imaginative, intellectual, sincere, heartfelt. One previous member continued writing even after dementia set in.

"A voice emerges from each person," she said. "Their personality comes through in the writing."

Books start coming

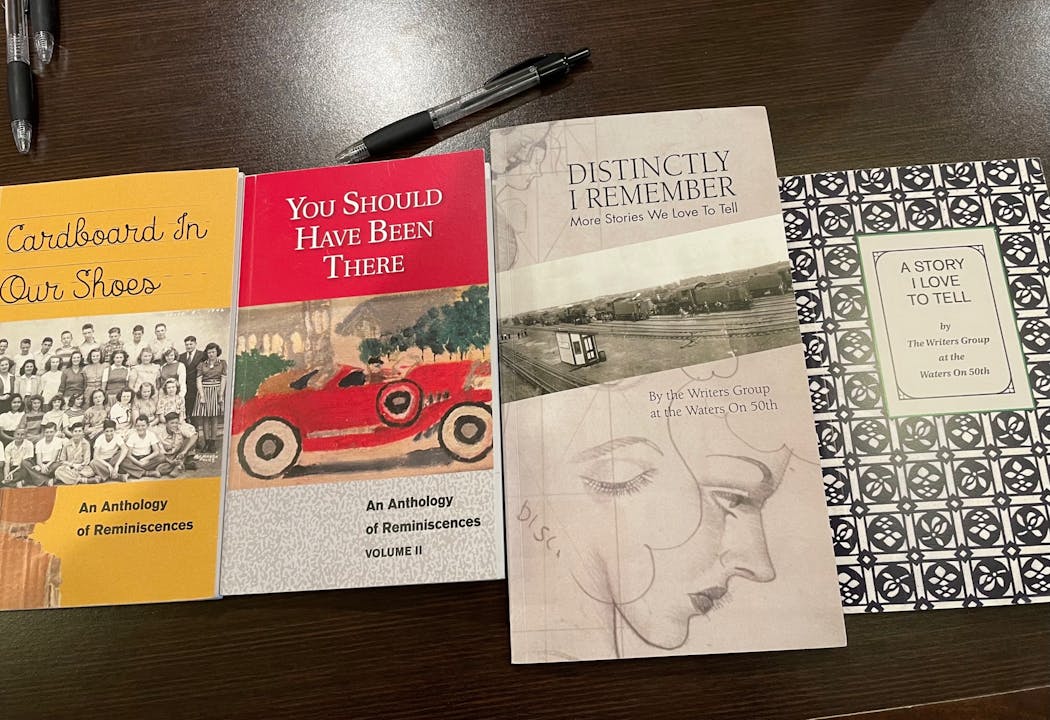

In 2016, the group published its first book, "Cardboard in Our Shoes: An Anthology of Reminiscences," which, as the subtitle suggests, included short essays about memories — including several about poor families inserting cardboard to extend the life of their footwear.

That was followed by "You Should Have Been There" in 2017, "Distinctly I Remember" in 2019 and "A Story I Love to Tell" last year. Written pieces are collected in chapters; the newest volume includes "Regarding Kindness," "Hidden Teachers" and "Riffs." Novak edited all of the books and had them published by a local printer.

Now there's talk of putting out a fifth book next year. Each publication is accompanied by a public reading at the Waters.

The prompt for this meeting's longer pieces was "The winds are mad. They know not where they come." It was a quote; Novak wasn't sure of the source, but one website cited it as the work of Robert Burton, a writer born in the 16th century.

Members had a month to write, though not everyone was satisfied with their results. "I had the hardest time with this, and what I wrote is really small," one said. "I always wish I could write shorter," another countered.

One wrote broadly, about her lifelong dreams of flying, wind farms, derechos. Another wrote about a scary accident on a camping trip when calls to her family for help were carried by the wind in the wrong direction.

Franco reminisced about a big red maple tree in her family's backyard, and how all five family members (Franco, her husband and their children) worked together every year raking the leaves. When a wind tore off a big branch and blew it onto a fence, the family decided they needed to take the tree down. The removal left a 10-foot tall stump. Not long after, the stump somehow started sprouting branches and leaves.

"In the next few years, it was like a new tree," Franco read. But that one, too, eventually "fell to difficulties of old age, and had to be removed," she said. Her children had left home by then. The tree became a poignant symbol of life's inevitable changes.

"I'm going to get it over with," Hansen said, before reading an account of her husband's descent into dementia, from "small lapses of memory," to changes in personality and driving close calls, eventually to the couple having to move from their home of 45 years.

Finally, Hansen said, her husband caught COVID and died.

"I never dreamed it would end without his family there to soothe him," she wrote.

"That must have been hard to write," Franco said afterward.

"It was," Hansen said. "And I could have written a thousand things."

"I'm just loving what you guys did with this topic, even if you hated the topic," Novak said. Next month's prompt, she announced, was "Imagine a morning in late November," a quote from Truman Capote's "A Christmas Memory."

Novak never offers critiques or suggestions for how members can improve their writing, she said. After all, they aren't working toward creative-writing degrees or book deals — those aren't the point of this group. It's more about building community, sifting through memories, expressing emotions, "having a voice," she said.

"I think the need to be heard is huge," Novak said. "I think that's what this is all about — that you still have a voice, that you still have an agenda."

The 5 best things our food writers ate this week

A Minnesota field guide to snow shovels: Which one's best?

Summer Camp Guide: Find your best ones here

Lowertown St. Paul losing another restaurant as Dark Horse announces closing