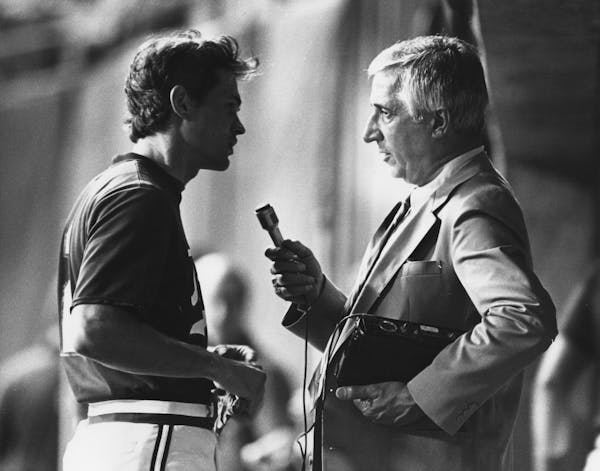

Sid Hartman was halfway home to reaching 101 years old when he died Sunday. The information first came in a tweet from his son, Chad, and instantly, social media was set aflame.

Many of those went with the traditional RIP. I have a question for all those going that route:

Are you nuts? Rest in Peace for Sid Hartman?

That's not a message of compassion for Sid. That's an insult.

OK, I'm sure Sid had a few peaceful moments in his century as a Minnesotan. He did fall on the ice and break a hip in 2016, and there had to be sedation involved, so there might have been a couple of hours when the then-96-year-old was put into neutral.

That didn't last, of course. Less than three weeks after the fall and the surgery, the Gophers held a news conference to introduce football coach P.J. Fleck, and Hartman was there — to hear Fleck's sales pitch, although more importantly to guilt the new coach into a sacred vow to make weekly appearances on Sid's Sunday radio show.

Here's my synopsis on RIP and Sid:

I first met him in August 1963 when hired as a sports copy boy for the Minneapolis Morning Tribune. Sid was both the morning sports editor and the provider of Hartman's Roundup five or six days per week. Staples of the Roundup were a half-dozen small mug shots — called half-column cuts — of people mentioned.

Sid would give one of the copy boys (aka, the victim) a list of six names. You would head for the library and go through the alphabetized drawers of half-column cuts. If a person on the list didn't surface, you would find a photo in the files to make a fresh engraving.

Early on, after a search as the rookie copy boy, I informed Sid that neither a half-column nor a photo of one of those parties existed.

Mr. Hartman did not take that information by resting in peace. In fact, if he wasn't so worried about the Gophers' upcoming season opener with Nebraska, he might have taken a moment to end my newspaper career right there.

Fifty-seven years later, with 20 as a competitor in St. Paul, and then 32 back in Minneapolis, I've been in Sid's company a couple of thousand times, and I've never seen a man at peace.

For decades, Sid and I also supported the same grocery store — the original Byerly's in Golden Valley. Back when the staff was more permanent, at least twice a month I'd be in line and the clerk would say, "Your friend was just in here."

Meaning Sid, to which I would usually offer a Sign of the Cross, but one day, I asked: "Did he offer congratulations on your fine service?"

"No," the capable woman at the checkout said, "he told me to 'hurry up,' as always."

You've heard of hurry up and wait? Sid lived by hurrying up and not waiting. That's what made him a great newspaper reporter. Demanding of sources, major and minor, "Tell me. Don't tell anyone else. Tell me … now." And, usually, he was so persistent, so forceful, that the source would crack.

One part of life lost to modern communications has been our former reliance on telephone operators. There can be no estimate as to the number of people providing operator assistance that Sid drove from the occupation with his belligerent demands.

On the night of Nov. 20, 1965 (I looked it up), Sid returned to the Tribune office around 11 p.m., handed me a phone number for a hotel in New Jersey, and said:

"Call the front desk and get put through to Paul Klungness. He's a Dartmouth running back from Thief River Falls. I want to have a note in the Saturday column."

I was no longer the rookie and said: "Sid … it's midnight in the East. Dartmouth is playing Princeton tomorrow. I can't wake up a player."

Sid said, "Call." The hotel operator refused to ring Klungness' room. Sid grabbed the phone. He didn't get Klungness, but she did let him wake up Dartmouth coach Bob Blackman and Sid got his quote on Klungness.

Sid would say, "You can get anybody on the phone," and he made that come 95% true — with persistence, impatience, drive to be not only first but also all alone with information.

I watched you in action for 57 years, Sid, and have full confidence in this: Rest in peace is the exact opposite of what made you a great newspaperman.

I'm also confident that, underneath all the distractions, decades on the radio, decisionmaking for the Lakers, pursuit of major league sports and new stadiums, baiting of officials conspiring against our teams, beat the strong heart of a great newspaperman.

And as now the senior sportswriter in the Twin Cities, I can add the reason Sid achieved that greatness:

For most of his career, he wanted it more than the rest of us, and he always needed it more — still needed it, in fact, seven months past age 100, and being there in print on the morning of his death.

Reusse: Twins play Giants, triggering Mays memories and a question: Can we get the Black players back?

Reusse: Twins have pitching, Buxton and (perhaps) sage advice to draw on

Reusse: Timberwolves fans are left with a loss to lament and a villain to jeer

Reusse: Twins and pitcher Canterino agree his full major league opportunity is worth waiting on