Alice Lieberman had planned to work for a few more years as a schoolteacher before the pandemic hit, but the transition to hybrid instruction did not come easily for her. She retired in summer 2021.

Her husband, Howard Lieberman, started to wind down his consulting business around the same time. If Alice Lieberman was done working, Howard Lieberman wanted to be free, too, so that the pair could take camping trips and volunteer.

The Liebermans, both 69, are one example of a trend that is quietly reworking the fabric of the American labor force. A wave of baby boomers has recently aged past 65. Unlike older Americans who, in the decade after the Great Recession, delayed their retirements to earn a little bit of extra money and patch up tenuous finances, many today are leaving the job market and staying out.

That has big implications for the economy, because it is contributing to a labor shortage that policymakers worry is keeping wages and inflation stubbornly elevated. That could force the Federal Reserve to raise rates more than it otherwise would, risking a recession.

About 3.5 million people are missing from the labor force, compared with what one might have expected based on pre-2020 trends, Jerome Powell, the Fed chair, said during a speech last month. Pandemic deaths and slower immigration explain some of that decline, but a large number of the missing workers, roughly 2 million, have simply retired.

And increasingly, policymakers at the central bank and economic experts do not expect those retirees to ever go back to work.

"My optimism has waned," said Wendy Edelberg, director of the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution. "We're now talking about people who have reorganized their lives around not working."

Millions of Americans left or lost jobs in the early months of the coronavirus pandemic as businesses laid off employees, schools closed and workers stayed home. Child care disruptions, COVID-induced disability and other lingering effects of the pandemic have kept some people on the sidelines. But for the most part, workers went back quickly once vaccines became available and businesses reopened.

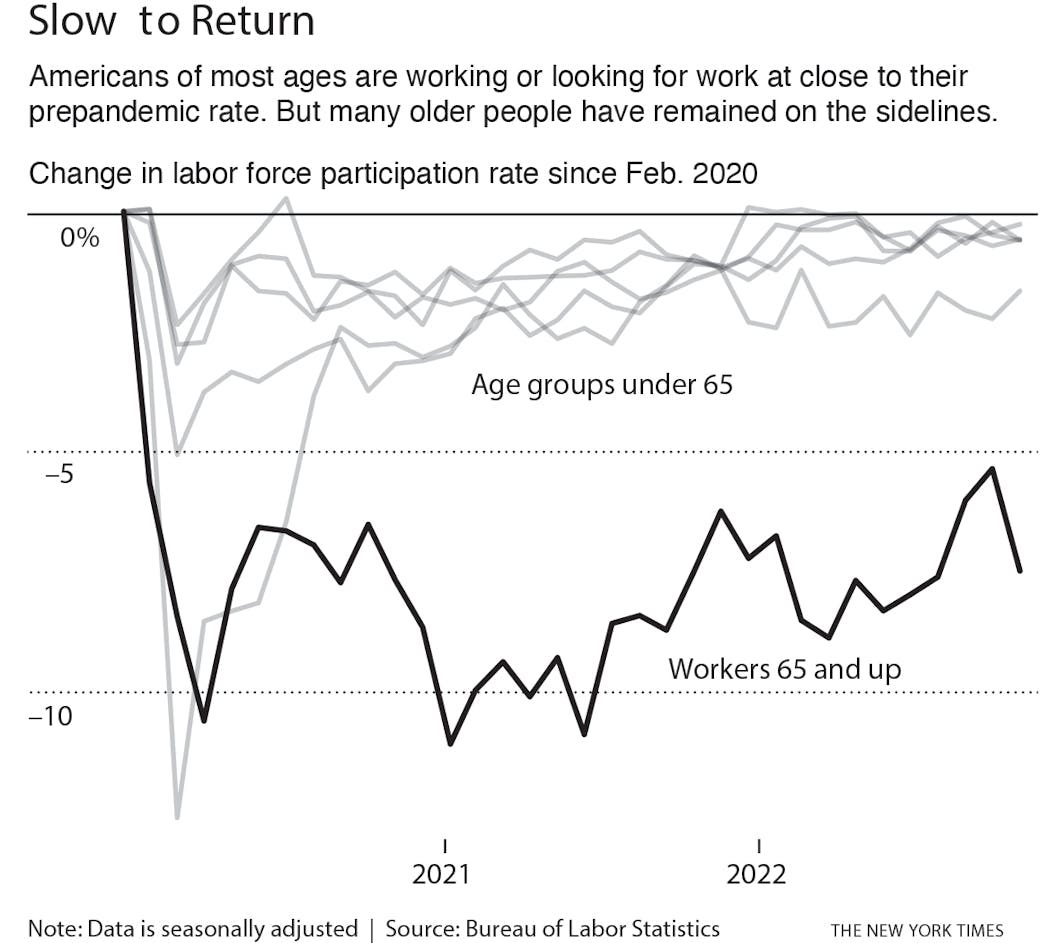

Older workers were the exception. Among Americans ages 18 to 64, the labor force participation rate — the share of people working or actively looking for work — has largely rebounded to early 2020 levels. Among those 65 and older, on the other hand, participation lags well below its pre-pandemic level, the equivalent of a decline of about 900,000 people. That has helped to keep overall participation steadily lower than it was in 2020.

"Despite very high wages and an incredibly tight labor market, we don't see participation moving up, which is contrary to what we thought," Powell said during his final news conference of 2022, adding: "Part of it is just accelerated retirements."

As would-be employees stay out of work, the resulting labor shortages have reverberated through the economy. Consumers are still shopping, and understaffed firms are eager to produce the goods and services they demand. As they scramble to hire — there are 1.7 job openings for every jobless person in America — they have been raising wages at the fastest pace in decades.

With pay climbing so swiftly, Fed officials worry that they will struggle to bring inflation fully under control. Wages were not a major initial driver of inflation but could keep it high: Businesses facing heftier labor bills may try to pass those costs along to their customers in the form of higher prices.

That risk is why the Fed is focused on bringing the labor market back into balance, and it is what makes the wave of retirees particularly bad news.

If America's missing workers were just temporarily sidelined, waiting to spring back into jobs given enough opportunity and a safe public health backdrop, nagging labor shortages might fade on their own. But if many of the workers are permanently retired — as policymakers increasingly believe is the case — bringing a hot labor market back into balance will require the Fed to push harder.

It can do that by raising rates to slow consumer spending and business expansions, tempering the economy and slowing hiring. But the process is sure to be painful and could even spur a recession.

Having fewer workers available "lowers the landing pad that the Fed has to lower the economy onto," Edelberg said. "Because of what's happened in the labor force, they just have to soften growth even more."

The Fed has learned the hard way that it can be a mistake to declare too confidently that a wave of workers is gone for good. In the years after the 2008 recession, policymakers began to conclude that the economy would soon run low on fresh labor supply.

They were wrong. Baby boomers, the huge generation of people born between 1946 and 1964, continued working later in life than previous generations had, providing an unexpected source of workers. Their importance is hard to overstate: The U.S. labor force grew by 9.9 million people between the end of the Great Recession and the start of the pandemic. Nearly 98% of that growth — 9.7 million people — came from workers 55 and older.

Unfortunately, there are reasons to doubt that retirees will serve as a surprise source of job market fuel this time. Boomers were in their 50s and early 60s when the economy began to emerge from the Great Recession. Many weren't yet ready to retire; others were just about to when the 2008 recession hit, eroding their savings.

Many decided to delay retirements as the labor market strengthened in the 2010s: They were relatively young, and they often needed the cash.

But key parts of that story have since shifted. The generation has aged, with older boomers now in their 70s and well over half in what would traditionally be considered their retirement years.

That makes a difference. More than six in 10 people between the ages of 55 and 64 work or look for jobs, but nudge up the age scale even a little and that propensity to work drops drastically. Three in 10 people between the ages of 65 and 69 participate. Between 70 and 74, it is more like two in 10.

In short, the demographic decks were always stacked for boomers to leave the labor market soon — but the pandemic seems to have nudged people who might otherwise have labored through a few more years over the cusp and into retirement.

"It's really coming from aging," Aysegul Sahin, an economist at the University of Texas at Austin, said of the decline in participation, which she has studied. "It was baked in the cake after the baby boom that followed World War II."

People over 65 do not work much for a variety of reasons. Some want to enjoy their retirements. Others want or even need to work but cannot because of poor health. In the wake of the pandemic, seniors may also be particularly alert to the risk of virus exposure at work, given how much more deadly the coronavirus is for older people.

"It could be that the oldest workers are more fearful of COVID," said Courtney Coile, an economist at Wellesley College. "Only time is going to tell whether the working-longer trend is really going to continue."

Still other seniors may be opting out of work for a more pleasant reason: Many are in decent financial shape, unlike after the 2008 downturn. Families amassed savings during the pandemic thanks to both government stimulus payments and price gains in financial assets.

It took until late 2010 for people between the ages of 55 and 69 to recover to their late-2007 wealth levels, according to Fed data. This time, an early-2020 hit had been fully recovered by June 2020. Financial wealth for that age group now stands about 20% above where it was headed into the pandemic, despite a recent market swoon.

And while inflation is eroding spending power, Social Security payments are price-adjusted, which takes some of the sting away.

The Liebermans in Pennsylvania, for instance, could go back to work part time if they needed to — but they do not expect to need to.

"Unless inflation went really ballistic, I think we'd be OK," Howard Lieberman said.

To be sure, while retirements could help keep workers in short supply across America, other factors could bolster the workforce. Immigration, for instance, is rebounding.

And some data paint a more optimistic picture of the labor force: Monthly payroll figures from the Labor Department, which are based on a survey that's separate from the demographic statistics, show that companies have continued to add jobs rapidly despite their complaints about a worker shortage.

"Listening to Jerome Powell talk about labor supply, he seems resigned to the idea that there's nothing left," said Nick Bunker, economic research director for North America at the Indeed Hiring Lab. "There are more workers out there who can get hired and want to get hired."

But central bankers have to make best guesses about what will come next, and, so far, they have determined that an increase in labor supply big enough to cool down the hot labor market is unlikely.

"For the near term, a moderation of labor demand growth will be required to restore balance to the labor market," Powell said last month.

Minnesota Department of Health rescinds health worker layoffs

Eco-friendly house on 30 acres near Marine on St. Croix listed at $1.6M

DOGE cuts federal money for upgrades at Velveeta plant in New Ulm