Reading Shawna Kay Rodenberg's "Kin" is like watching anything made by director David Lynch.

After each sentence, paragraph or turn of the page, I expected the likes of the Lady in the Radiator from "Eraserhead" to show up, all puffy-cheeked and singing eerily about heaven, or any of the backwards-speaking characters in "Twin Peaks." But "Kin" is not someone's too-surreal-to-be-believed nightmares written for the screen, but someone's living nightmare detailed in a memoir.

The horror of Rodenberg's life begins within The Body, "an end-times wilderness community, cloistered in the woods of northern Minnesota," which her father joins when "he was red-eyed and mad with fear, following his tour of duty in Vietnam."

Her family leaves behind a life in Kentucky, with its accompanying possessions and people, for a spare existence near Grand Marais, where Bible study ("Our family was bilingual, and Bible was our second language") and traditional roles are upheld. Mostly Rodenberg tries to evade her father's wrath, which she blames on herself, as children do, because she "found being good impossible."

Misery in myriad forms dogs her, and refuge is difficult to come by, but Rodenberg finds it in art, music and books, particularly the work of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Despite the prohibition against possessions, she is given a set of the "Little House" books as a birthday present and reads them over and over again, eventually realizing that Wilder was "unlucky in life until she began writing her own story."

But Rodenberg doesn't keep to her own story. She intersperses third-person accounts of her mother's life in Kentucky and her father's before he went to Vietnam, including pages — perhaps too many — of letters he wrote to his parents while he was stationed there. The change in perspective is jarring, heightening the surreal aspects of the book and emphasizing its Southern gothic aesthetic.

Ultimately, though, the alternating chapters provide context and feed Rodenberg's overarching theme about how stories repeat in families, that lineage "wasn't about the past, like people often thought, so much as the future, and no matter how a person might try to trick destiny, most people ended up as carbon copies of their parents and even ancestors they never knew."

With its focus on religion, a father figuratively blinded by its tenets and his own pain, the fallout from growing up in an unstable environment and the attempts to overcome it, "Kin" begs comparison to Tara Westover's 2018 memoir, "Educated." Westover's work is much more optimistic, however, despite the horrors inflicted by her Mormon survivalist parent. The odds may have been long, but Westover's ending has a Hollywood quality. There is no such feeling in "Kin."

Even though Rodenberg strives for a tidy ending for herself, obstacles keep popping up. And why shouldn't they? Life isn't neat, and she leans into that, digging deep with dense but readable prose and providing compelling insights. Besides, her life doesn't end with the memoir's last page. There's always more to be said. Here's hoping she will.

Maren Longbella is an editor at the Star Tribune. • 612-673-4012

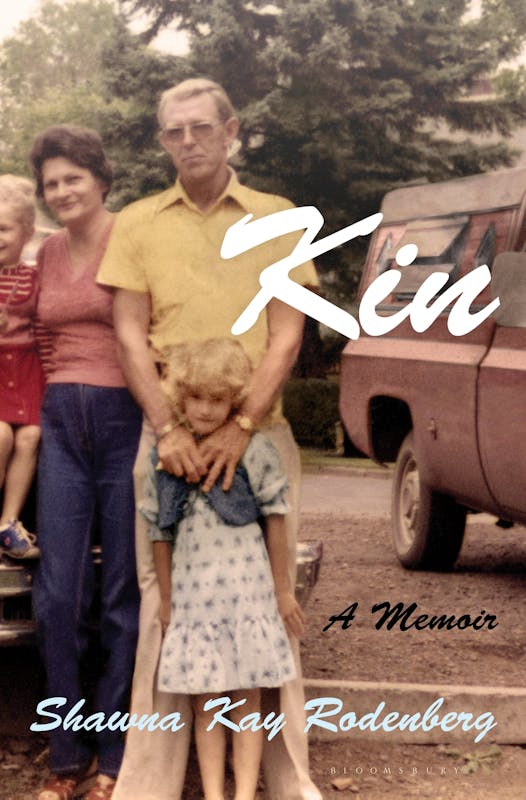

Kin

By: Shawna Kay Rodenberg.

Publisher: Bloomsbury, 352 pages, $28.

Event: 7 p.m. June 10, Zoom event hosted by Next Chapter Booksellers. Register at https://bit.ly/2R5jR5D.

The 5 best things our food writers ate this week

A Minnesota field guide to snow shovels: Which one's best?

Summer Camp Guide: Find your best ones here

Lowertown St. Paul losing another restaurant as Dark Horse announces closing