Erica Foster got started in gymnastics much like most young girls. Recently graduated from Minnetonka High School, Foster began 12 years ago in the traditional world of artistic gymnastics, with its four distinct disciplines: floor exercise, uneven bars, balance beam and vault.

Then she was exposed to rhythmic gymnastics, and her gymnastics life took a sharp turn.

Rhythmic gymnastics, which combines grace, fluidity of movement and flexibility with elements of dance, is a distant second to artistic gymnastics in the United States in popularity. Unlike artistic gymnastics, rhythmic gymnastics incorporates props, called apparatuses, into its routines: a hoop, a ball, a ribbon and a pair of small clubs.

While the other kids were working on the tumbling passes, somersaulting vaults and precision balance beam routines that mark artistic gymnastics, Foster was smitten with rhythmic gymnastics.

"I just fell in love with it and the challenge it brings every day," Foster said. "And I can catch, too."

A valuable trait in rhythmic gymnastics. No real tumbling or flipping exists in rhythmic gymnastics, which tends to bewilder American audiences accustomed to soaring gymnasts.

Foster, of Chanhassen, and Victoria Gonikman, who will be a senior at Wayzata High School in the fall and lives in Corcoran, are prize pupils at NorthWest Rhythmic Gymnastics in Plymouth. Both are members of the U.S. rhythmic gymnastics national team, having achieved "elite" status, and will compete at the national championships that begin Monday at the Minneapolis Convention Center. The meet precedes the U.S. Olympic trials for artistic gymnastics, which will take place Thursday through Sunday at Target Center.

Rhythmic gymnastics was first developed in Russia. Each routine is done with one apparatus, which is thrown in the air, often 30 feet or higher, while the performer runs through an acrobatic, ballet-influenced routine choreographed to music.

Dropping an apparatus or throwing it too low can dagger a routine. Rhythmic gymnastics judges are notoriously exacting and punitive.

Which is why NorthWest Rhythmic owner and U.S. national team coach Svetlana "Lana" Leonova, a native of Moscow who emigrated to Minnesota 28 years ago, sweats the little things.

"It takes years and years to master," Leonova said.

She pointed out the precision balance technique called "penché balance" as an example. Foster and Gonikman then demonstrated, doing leg lifts in which one leg stays stationary while the other is slowly lifted behind them until the legs are 180 degrees away from each other.

All that while on their toes with the stationary leg, as required.

Witnesses unfamiliar with the move, which is common in rhythmic gymnastics, can't fight a gasp as it unfolds.

"It's the first step to start. It's a basic move. You want to get full amplitude," Leonova said.

Artistic gymnastics' explosive moves often draw raves, but witnessing the requirements of rhythmic gymnastics can be eye-opening.

"Strength is very important," Leonova said. "The gymnasts look very light. If you look at them, you will never say, 'This is an athlete.' But they have incredible strength."

Neither Foster nor Gonikman expects the crowds for the rhythmic gymnastics meet to rival those of the larger, more prominent meet. Both are hoping to better their position on the U.S. team to land one of the few available spots for future international competition. The single Olympic spot has already been secured.

Foster was a U.S. silver medalist with the ball apparatus last year and won bronze medals in the all-around, ball and clubs at the U.S. championships in 2022. She was a member of the world championship team in 2021. Her quest for international competition was scotched when she tore a ligament in her left foot in February. She is mostly healed now and is back up to eighth in the U.S. senior elite rankings.

Gonikman was a U.S. junior national team member in 2021 and had numerous top eight finishes in elite-level competitions in 2022, '23 and '24.

Rhythmic gymnastics has not caught on in the United States the way artistic gymnastics has. That disappoints Leonova because rhythmic gymnastics enjoys much greater popularity in Europe.

"They have so many fans over there," Leonova said. "This is the most popular sport for girls. These girls are treated like rock stars wherever they go."

She believes rhythmic gymnastics just needs a breakthrough moment to spur broader interest.

"We haven't won gold medals," Leonova said. "When we win gold medals, then it will happen."

Until that happens, Foster and Gonikman and the rest of the gymnasts at NorthWest Rhythmic are content to respond to uninformed questioners and bask in the spotlight when it comes.

"When we take our hoops on the plane with us, people get excited and ask if they can use it," Gonikman said. "We tell them no."

"Everybody asks us if we can do a cartwheel," Foster said.

That move is not a part of rhythmic gymnastics routines, but Foster gave a mischievous grin. "Of course we can," she said. "We're gymnasts."

Both are excited to have the national gymnastics spotlight on their hometown for the upcoming week.

"I'm excited about it," Gonikman said. "It will be nice to have people come out to watch us."

Leonova even has plans to bring girls from her club to the Olympic trials. But what she wants most is to see her girls shine on the floor.

"I want steady routines. No big mistakes, everything finished for credit," she said. "Focused routines. That's all I want from them. I want their best performance, and they are ready."

Tampa Bay gets early home runs, shuts out Twins 5-0

Minnesota Frost to celebrate second Walter Cup with downtown St. Paul parade and party

RandBall: The 10 things you need to know today in Minnesota sports

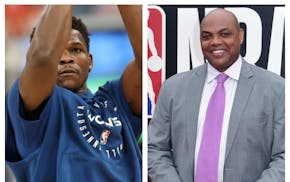

Charles Barkley: 'Don't try to make Anthony Edwards the face of the NBA'