Hennepin County's emergency shelter system didn't have enough space last year for everyone who needed it. More than 4,000 times in 2023, a person called the shelter hotline to reserve a bed for the night only to be told everything was booked, or that they weren't eligible to stay in a shelter because they had previously violated the rules.

Still, shelter beds were used more than 167,700 times during the same period. And homeless single adults were turned away far fewer times last year than in 2022, when there were 7,000 turn-aways.

"It's positive to see it trending in a direction that the system is better able to meet people's needs in real time," said David Hewitt, director of housing stability for Hennepin County. "The last few years have been pretty tumultuous years economically and socially, and that creates its own variation in terms of how many people are falling into housing crisis at any given time."

Hewitt credits the county's investments in case managers, who help people surmount complex barriers to obtaining housing on their own, for the decline in turn-aways. From 2021 to 2023, Hennepin saw a 57% increase in the number of people leaving homelessness and finding permanent housing, he said. By the end of 2023, the number of people that the county had identified as chronically homeless — not having a home for at least a year and having a disability — dipped below 300 for the first time since the county started tracking the population in 2017.

Moving people who had been living in emergency shelter for years into housing has freed up beds for the short-term stays that shelters were designed for, Hewitt said. A new diversion hotline run by Catholic Charities Twin Cities has also helped prevent shelters from overflowing.

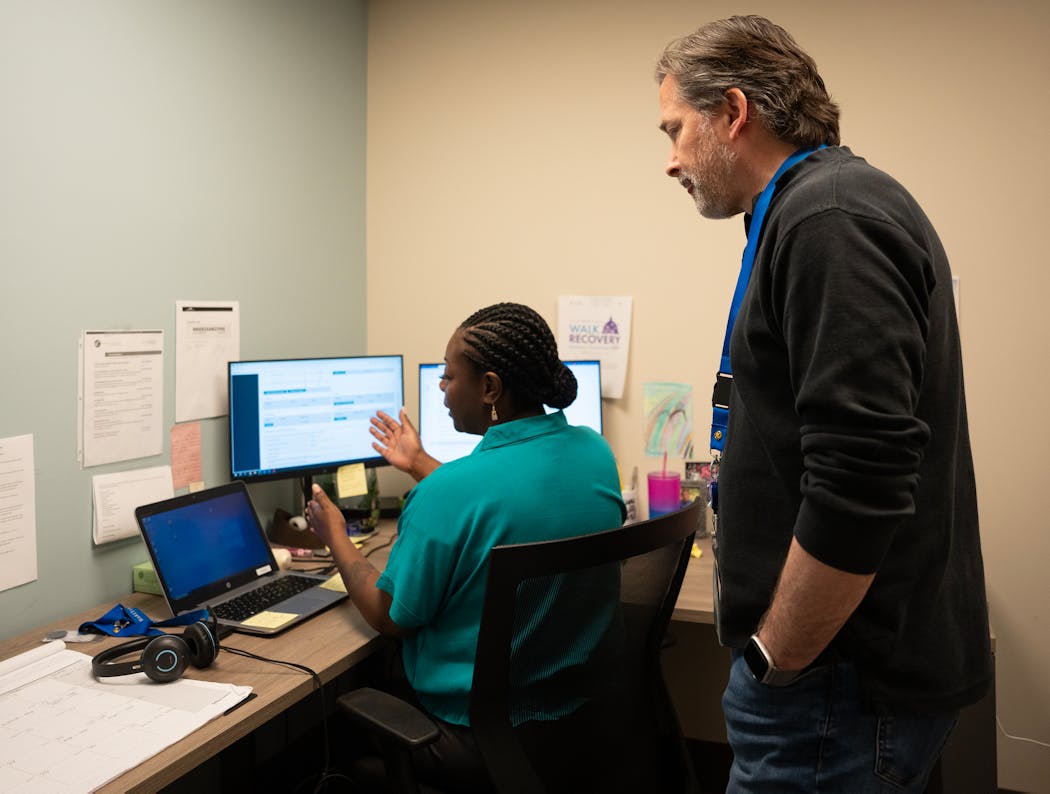

Launched in January 2023, the Hennepin Shelter Hotline is the number anyone experiencing homelessness can call. On the other end of the line are Catholic Charities operators who identify people entering homelessness for the first time and try to help them find creative ways to stay out of the shelter system.

Alanna Hinz-Sweeney, who oversees the program, says operators will mediate with landlords and help people resolve conflicts with relatives, arrange transportation and offer gift cards for food or air mattress rentals if that will make it easier for a friend to take them in. Victims of domestic violence get connected with the Day One statewide program. If someone is on the verge of being evicted, the operator can refer them to rent assistance and tenant advocacy organizations. If shelter ends up being the only option, they're transferred to the reservation system.

"As the caller is telling their story, our staffers are really actively listening for solutions the person may share but maybe they haven't realized it because they're in crisis," said Hinz-Sweeney. "Sometimes as we're talking through the situation, they'll come to the resolution because they just needed someone to be that sounding board and to listen non-judgmentally."

The calls can take the better part of an hour, but about 80% of callers call just one time, Hinz-Sweeney said, indicating that diversion is working.

As the shelter system continues to redesign itself incrementally to better serve people experiencing homelessness, people are still falling through the cracks. Numerous encampments dot Minneapolis neighborhoods, and it isn't hard to find people living in tents who have had negative, even traumatic, experiences with shelters in years past.

Jorge Grijalva, who was living with his girlfriend of eight years in a yurt at 2839 14th Av. S. as of Wednesday, said he's called the shelter reservation line many times to find that the only beds available were at Salvation Army Harbor Light in downtown Minneapolis, where men and women are separated on different floors. His girlfriend struggles in shelters and has been kicked out of them before, so they prefer to stick together. First Covenant Church, operated by Agate Housing, takes couples, but space has always been limited, Grijalva said.

"It's hard to get into," he said.

Chris Rabideau, another encampment resident, said his younger brother had just been accepted into the Homeward Bound shelter, operated by the American Indian Community Development Corporation, after trying to get a placement there for weeks, a process complicated by his brother's lack of a phone.

People who are turned away from Hennepin County's shelter system during the day after all beds are reserved can try again in the evening in case there are no-shows. But Rabideau said he prefers to camp outdoors, despite the constant threat of sweeps, because waiting around all day on the chance that he might reserve a shelter bed one night at a time feels less certain to him than pitching a tent.

"If you have a chance of getting rejected, I won't go waste my time," he said. "Why go waste hours when you're not guaranteed a spot?"

Anyone experiencing homelessness can call the Hennepin Shelter Hotline at 612-204-8200.

Star Tribune data editor MaryJo Webster contributed to this report.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?