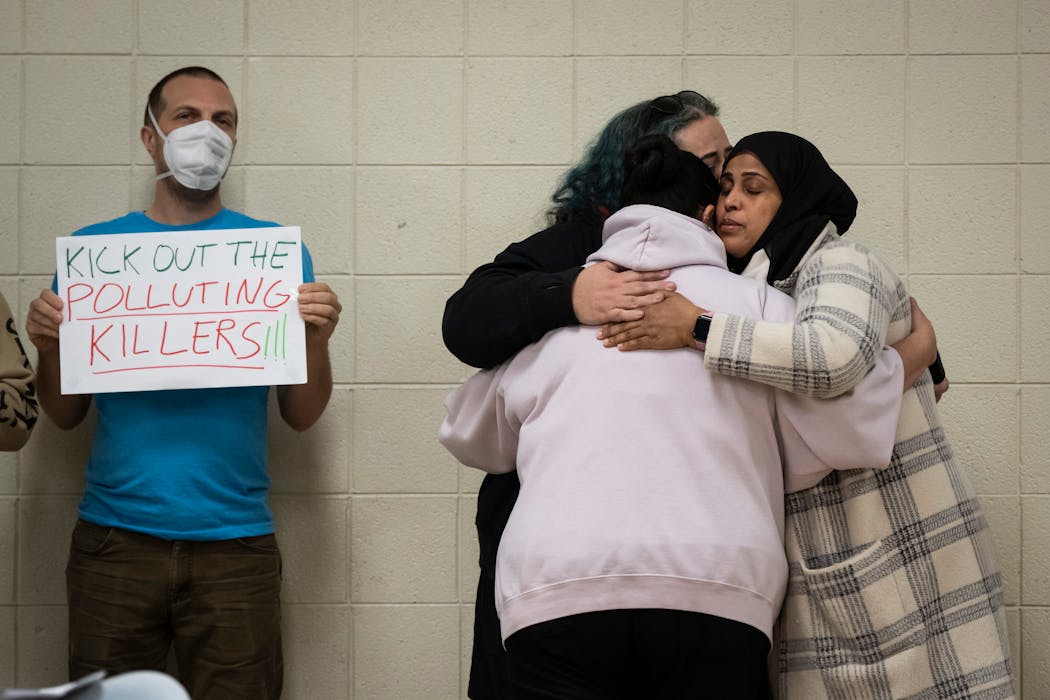

A standing-room-only crowd confronted state and federal environmental officials on Monday night, sharing years of health concerns and freshly stoked anger over the oversight of a Minneapolis metal foundry.

Residents of the East Phillips neighborhood and the nearby Little Earth community told stories about their children and grandchildren struggling with breathing problems and cardiac conditions. Nearby, Smith Foundry has operated for a century, making iron castings on E. 28th Street.

One mother cried as she talked about worrying if her child's day care had put them too close to pollution and led to an asthma diagnosis; a man who identified himself as a foundry worker said that people in his industry are known to die young; and many people shared stories of developing asthma cases or finding dust in their homes.

"I don't want to see nobody else bury a child," said Cassandra Holmes, a former Little Earth resident who said her son had been diagnosed with a heart condition at 14 and died at 16. "It's the worst feeling in the world."

Anger has roiled the neighborhood since it was revealed earlier this month, first by a report in Sahan Journal, that federal inspectors had found evidence of several potential violations of the Clean Air Act at Smith.

EPA inspectors paid a surprise visit to the foundry in late May and found a broken air filter and ductwork, and visible particulates building up on surfaces and escaping through doors and windows. In a draft list of violations written up in August, the agency claimed the foundry had been polluting its neighborhood's air and breaking air quality limits for five years.

The pollution singled out in EPA's report was fine particulate matter — a dangerous form of air pollution that can cause heart attacks, asthma and chronic health conditions. Smith is also Hennepin County's biggest source of lead emissions, though no agency has claimed the foundry is breaking a limit for that pollutant.

Before this visit, the last time MPCA inspectors had been inside the building was in 2018. The agency subsequently paid a visit on Nov. 6 and saw no evidence of problems.

Adolfo Quiroga, president of Smith Foundry, spoke only briefly at the end of the Monday meeting.

"We are committed, and I mean it, we are committed to be a good neighbor," he said. "Forty-five percent of union employees live in the area, and we are committed to meet all the standards, or exceed them, as imposed to us."

In response, the crowd barraged him with repeated entreaties for the foundry to close. One woman who said her father has worked at the foundry told Quiroga that children and the elderly were suffering from their work.

The MPCA has pushed back on parts of the EPA's conclusions, telling the Star Tribune last week that it has no evidence Smith has broken air pollution limits, and that the EPA could have misinterpreted data. EPA stood by its calculations.

Brian Dickens, a representative of the EPA's Chicago office, said during the meeting that it is not unusual for the EPA to do inspections across the country.

"It's not that the state agency is not doing its job. It might be that we have the expertise. We have advanced monitoring equipment," he said. "Relative to other states, Minnesota's environmental regulations are strong"

Dickens also said there would be a test of the air coming out of the smokestack at Smith on Dec. 12. He did not, however, comment in specifics on the EPA's investigation of the facility.

MPCA's assertion that it didn't have evidence of Smith breaking air quality standards proved a controversial one at the meeting, where many attendees said the claim effectively ignored years of complaints from the community.

"I am sorry that is how it feels," MPCA Commissioner Katrina Kessler said. "That is not my intent."

Kessler's words did little to keep the crowd from calling for her resignation.

People in the room insisted that many years of attempts to abate poor smells and pollution from Smith and its next-door neighbor, asphalt plant Bituminous Roadways, had fallen on deaf ears.

"It's been decades that this [foundry] has been polluting our community," said Joan Vanhala, a 40-year resident of the neighborhood. She said that as long ago as 1995, the neighborhood had tried to strike a "good neighbor" agreement with Smith, but nothing came of it.

Other questions focused on the facility's permit, which dates to 1992. Since then, Minnesota passed a law that requires regulators to apply stricter air standards to a large swath of south Minneapolis that has historically faced pollution, including East Phillips.

Cassandra Meyer, the MPCA permit engineer who has been working to update the foundry's permit since 2016, told the room that the agency aimed to finish the permit by the end of 2024, with many more public meetings in the process.

Meanwhile, MPCA has previously said it struck an agreement with Bituminous Roadways to close by the end of 2025.

But overwhelmingly, people in the room called for the foundry to be shut down entirely. Some said they were not even comfortable with the two-year timeline for Bituminous to close.

Faced with a barrage of questions about whether MPCA could pressure the facility to close, Assistant Commissioner Frank Kohlasch demurred.

"The best I can promise you tonight is that we will continue to have transparent [discussions]," he said.

Evan Mulholland, an attorney with the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, called issues with the permit a distraction and said that the goal of shutting down the foundry would not happen through MPCA.

"The permit is permission to pollute," he said.

The MPCA will hold another meeting via Zoom from 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. Friday.

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?