After spending millions of dollars and tracking hundreds of moose with GPS collars, scientists have pinpointed the primary culprit behind the animal's ever-shrinking numbers in Minnesota.

It's the deer. Parasites they carry into Minnesota's North Woods have emerged as the leading cause of death for moose, state and tribal biologists have concluded.

But solving that mystery creates a thornier one: How can state wildlife managers balance efforts to save the iconic moose with the demands of hunters who want more deer in Minnesota's far North Woods?

Minnesota has an estimated 500,000 deer hunters, and they provide about $20 million a year to the state Department of Natural Resources while supporting powerful and well-organized hunting organizations.

"We don't have a Minnesota Moose Hunters Association," said Carrol Henderson, nongame wildlife manager for the DNR.

The strong pull of Minnesota's whitetail culture and its economic impact show up loud and clear in DNR surveys of landowners and hunters in that part of the state, as well as in the sometimes-contentious debate among citizen committees that advise the DNR on deer management.

"Deer hunting brings in more money to the state than moose," said Randy Bowe, a longtime hunter on the North Shore of Lake Superior and owner of a taxidermy business in Duluth. "I don't know of anyone who purchased land to moose hunt."

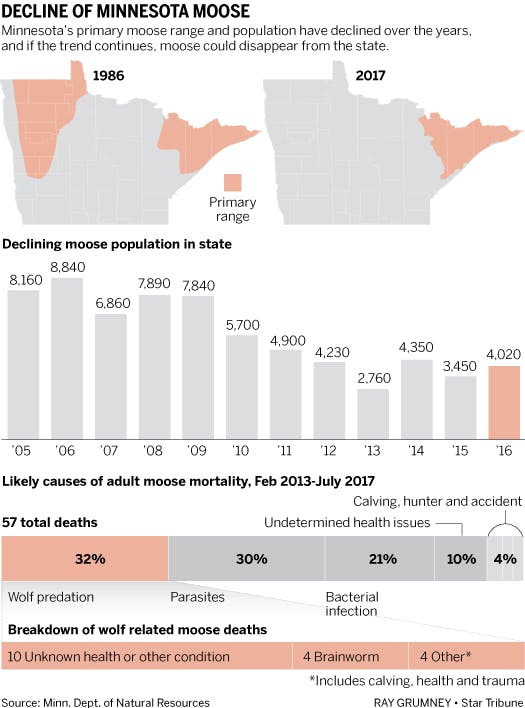

Minnesota's pine forest has always been the most southern edge of the moose country that stretches across the northern part of the continent. The huge animals used to roam across the top of the state, numbering more than 8,000 as recently as 2005. But in the past 12 years their numbers plummeted, and the 4,000 or so that are left congregate in the Arrowhead region between the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and the North Shore.

The speed of their demise flummoxed biologists and launched some of the most ambitious moose research projects ever conducted — one by the DNR and another by the Grand Portage Band of Chippewa. Both relied on sophisticated satellite-connected GPS collars that tracked moose through their daily lives, and many to their deaths. Between the two studies, about 83 carcasses, or parts of them, were extracted from the woods and trucked to the University of Minnesota for moose autopsies.

They found that moose die for a lot of reasons. Wolves and bears eat their young and injure the adults. Bloodsucking ticks, which survive shorter winters in ever-greater numbers, weaken them. And the impact of climate change is still an open question.

But a parasitic brainworm that deer tolerate — and moose don't — is either directly or indirectly related to one-fourth to one-third, perhaps more, of moose deaths, said the biologists leading the research.

"It's really affecting our moose in the wild," said Michelle Carstensen, who heads the state's $2 million moose mortality project.

Overall, wolves kill slightly more adult moose than the parasite, but a significant portion of those kills were moose already infected by deer parasites and vulnerable to attack, she said.

Bad neighbors

Deer are relative newcomers to the northeast corner of Minnesota. Over the past 150 years, their numbers have risen along with the humans who built roads, cleared the trees, and created the open landscapes deer prefer.

Tony Swader, a longtime hunter and a member of the Grand Portage band, said tribal elders recall seeing a few deer along the Pigeon River that forms the Canadian border, but anyone who was serious about hunting them used to have to go at least as far south as Duluth.

Moose was historically a primary source of meat and a cultural touchstone for the Ojibwe, and members of Swader's tribe still hunt a few bulls on reservation and treaty lands.

But on the reservation, deer now occupy a fourth of moose territory, said Seth Moore, the tribe's environmental director. And tribal members harvest far more deer now because that's what's there. As a result, the culture is shifting as well, he said.

"Fewer kids learn about moose," he said.

Deer and moose weren't made to share the forest. Deer are native to the southern part of the North American continent, and over hundreds of thousands of years, they evolved to withstand the parasites they carry. Two of those parasites are problematic — brainworm and liver flukes — and both spend part of their lives in slugs and snails. Deer eat the snails and slugs while browsing, and the microscopic brainworms make their way to the outside of the deer's brain, where they lay the eggs. After hatching, the larvae move through the digestive tract and out in feces, where they are picked up again by snails. Liver flukes start in the liver, but end up back in snails by the same route.

Moose pick them up the same way — by eating snails while browsing. But moose, which are believed to have crossed over from Siberia just 70,000 years ago, have not developed the defense mechanisms that deer have, and the parasites can damage their brains, nervous systems and livers.

With brainworm, moose often develop a characteristic head tilt, and the infected moose are often the ones seen wandering aimlessly where they shouldn't be — like roads.

"You can't have moose and whitetails together," said Margo Pybus, an expert on deer parasites at the Fish & Wildlife Division in Alberta, Canada. "Unless we want to wait 60,000 years until moose get the parasite relationship figured out."

Biologists say there are solutions, but at this point few are workable. Forest fires, once a natural process, used to provide moose with better food and habitat while suppressing all kinds of parasites. But today, big fires put people and property at risk. Lowering the wolf population might reduce predation on calves, but wolves kill far more deer than moose; and as long as they are protected as a threatened species, killing them is not permitted.

That leaves hunting.

"If I were king of the world," said Moore of the Grand Portage Band, "I would aggressively hunt deer to the point where the population declines."

But he gets resistance to that, he said, and so does the DNR.

"I have tribal members who are furious with me for trying to manage the deer population," Moore said.

'I can't hunt them'

This year for the first time the DNR took steps to manage deer with moose in mind. Deer hunting "permit areas" in the far northeast corner of the state have been reconfigured to more clearly designate moose regions and reduce deer numbers there relative to other parts of the state.

But biologists argue that the state could do more for the sake of the moose.

For instance, the deer population goals around the perimeter of moose country are considerably higher than inside, and deer are known to migrate for many miles. And within the deer permit area around Grand Marais and up to Canada, current hunting rules are designed to increase deer numbers slightly.

"No, I don't think a harvest strategy designed to increase deer numbers is helpful for moose," said Mike Schrage, wildlife biologist for the Fond du Lac Band of Chippewa. That permit area, he said, "contains some of our best remaining moose country."

Steve Merchant, the DNR's wildlife populations manager, said that if protecting moose were the only consideration, cutting deer numbers would make sense. But human politics influence the agency's decisions, too, he said. There are, after all, far more deer hunters than moose in that part of the state — some 11,000 bought permits to hunt there last fall.

"Some deer hunters don't think we should worry about moose," Merchant said. That's not the majority, he added, but there are some who think " 'why should we care for moose, I can't hunt them," he said.

Bowe, the taxidermist from Duluth, had an even more fatalistic perspective.

"If you believe in the theory of global warming, moose are at their southern range and won't be able to survive anyway," he said. "That's my take on it."

Craig Engwall, executive director of the Minnesota Deer Hunters Association, said that it could make sense to lower deer numbers in moose range, but only if there is clear science to support the benefit and a transparent public process that goes with the decisions. In the meantime, the association is part of a $3 million project to improve moose habitat through logging to encourage patches of new forest growth and better forage.

What about the snails?

At the University of Minnesota, scientists are studying a third species that could change the equation: snails.

Deer and moose have to eat "tens of thousands of snails to be infected," said Tiffany Wolf, an animal epidemiologist at the U's School of Veterinary Medicine, who is working with the Grand Portage band to solve the puzzle. She wants to do genetic research that could reveal which snails end up in moose and deer feces and could help break the cycle of transmission.

Because tamping down on the number of snails, she said, would be a much easier sell than getting rid of the deer.

Josephine Marcotty • 612-673-7394

Want to share info with the Star Tribune? How to do it securely

'Safe recovery sites' would offer syringes, naloxone and more to people using drugs. The plan could be in peril.

New Minnesota GOP leaders seek peace with party's anti-establishment wing

Who is Republican Lisa Demuth, Minnesota's first House speaker of color?