It would be easy to overlook the headquarters of Medical 21 Inc., tucked in a low-slung brick building in a Plymouth business park. The unremarkable exterior belies the personality of the company's founder and chief executive inside.

Manny Villafana is a legend in Minnesota medical technology and beyond — but not someone who rests on past successes. At age 81, he is on his eighth startup with Plymouth-based Medical 21, which he founded in 2016.

From his desk, surrounded by a museum-like collection of old pacemakers, Villafana explains his vision through parables. Only they aren't parables, but true stories from his past that showcase his entrepreneurial zeal.

For half a century, he has launched, expanded and sold medical startups that have helped define, shape and amplify Minnesota's medical technology industry.

His legacy is anchored by two companies he started in the 1970s: Cardiac Pacemakers Inc. (CPI) and St. Jude Medical Inc. Abbott Laboratories bought St. Jude for $25 billion in 2017.

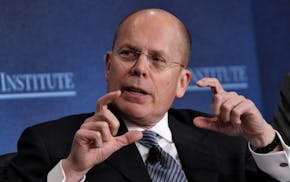

"He really is one of those early serial entrepreneurs that has really shaped the ecosystem for medical technology," said Scott Ward, chief executive of New Brighton-based Cardiovascular Systems Inc. and a Medtronic veteran.

With the next medical frontier always beckoning, Villafana just won't quit.

"When golf is as exciting as what I'm doing, maybe I'll play golf," said Villafana.

Every weekday morning, he wakes up 5 o'clock, goes to the gym, eats breakfast and is at his desk by 9 a.m.

Medical 21's concept is to develop an artificial artery that can be used in cardiac bypass surgery, replacing the need to harvest blood vessels from elsewhere in the body — such as the legs, arms and chest. For decades, dozens of companies have tried to do the same thing, with no success. Villafana calls the quest "the holy grail of cardiac surgery."

With an entrepreneur's optimism and ambition, he is undeterred.

While working at Medtronic early in his career, Villafana suggested that it start making pacemakers with lithium batteries. Medtronic wasn't interested. At the time, several companies were making pacemakers that lasted only 18 to 24 months. Villafana saw an opportunity and left his job to found his first startup, Cardiac Pacemakers Inc., in 1972.

From a telephone booth in the downtown Minneapolis skyway, he raised $50,000 to start CPI.

"I didn't have an office," Villafana said. "I used to plug in the 25 cents or nickel or whatever it was, and that's how I raised money."

The company's first pacemakers used lithium batteries and came with an initial guarantee that the device would last three years. Lithium batteries have long since become the standard for all pacemakers.

CPI was sold in 1978 to Eli Lilly and Co. for $127 million, which was later spun off with the medical device unit and eventually acquired by Boston Scientific Corp.

Villafana founded St. Jude Medical in 1976; the company introduced the first bileaflet, all-carbon heart valves that soon became the industry standard. Before St. Jude, heart valves were ball valves; the bileaflet version had two flaps that pivot for better blood flow.

In 1987, Villafana founded Helix BioCore Inc., which later changed its name to ATS Medical Inc. and was acquired by Medtronic in 2010 for $370 million.

Villafana's influence and impact locally is still felt today. Boston Scientific has more than 10,000 employees and Abbott has about 5,000 employees in the state. Manny's Steakhouse, a downtown Minneapolis dining institution, is named after Villafana, who seeded the restaurant owner's startup costs.

The Manny approach

Perhaps as important as the technological advances made by his companies was Villafana's pioneering approach to relationships.

"He began that process of closely interacting with cardiac surgeons, interventional cardiologists and really understanding their needs for the product and for education," Ward said.

In the 1970s, it was rare for medical device companies to train surgeons and medical fellows on their product. But that's exactly what Villafana did.

"The reason that [St. Jude Medical] retained their market share for so many years is because they trained and educated all the fellows, all the cardiac surgery fellows, on how to do heart valve implants, and what they were trained on was the St. Jude product," said Ward. "That was all Manny. Manny is all about those close customer relationships."

Today, that's common practice in the business.

Villafana grew up in the South Bronx, the son of Puerto Ricans who had — as he put it — "nada, nothing." His mother, father, and his three brothers all died of heart attacks, so it's no coincidence his career has focused on cardiac health.

"My entire family died of cardiac disease," Villafana said. "They all died too young."

Cardiac bypass procedures are a very common surgery. The market is estimated at $8 billion, Villafana said, "much bigger than anything I've worked with before."

Villafana never went to college and holds an honorary doctor of science degree from the University of Iowa. Yet when talking about the human heart and the device his company is developing, Villafana could pass as a doctor to a layman's ears.

Successes and failures

The key to creating an artificial artery is ensuring that the body will accept the material and won't itself lead to other complications. Medical 21 has licensed its technology from the University of Iowa but is making updates. The artificial artery itself looks like a very soft pipe cleaner, made with a synthetic material and a nickel-titanium alloy wire.

Medical 21 wrapped a financing round in December; the company has raised $11 million since its inception. Villafana has taken seven companies public and expects Medical 21 to be his next. The company is looking to raise an additional $30 million to $40 million through a regulation A+ offering, sometimes called a "mini-IPO."

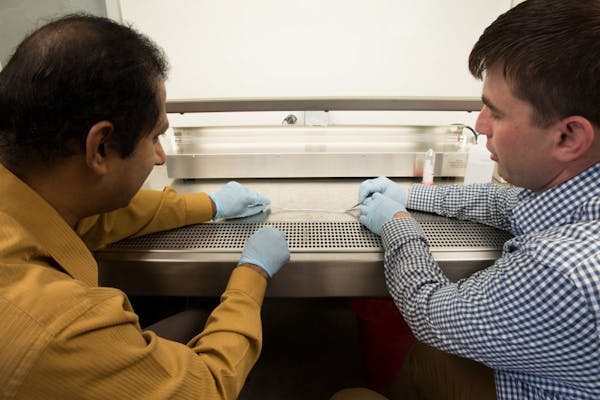

In 2017, Medical 21 began testing the product on animals, first in pigs and then in sheep.

Lyle Joyce, a professor of surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin, is on Medical 21's medical advisory board. His son David Joyce, also a cardiac surgeon, is also on the board.

Villafana "is working in an area where there is a tremendous need," Lyle Joyce said.

The father and son duo have implanted grafts in some animals. "It went very well," said Lyle Joyce. "The present design is beautiful."

Medical 21 hopes to start clinical trials of the artificial artery in the second half of the year in the United States and Europe. Potential U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals are still several years away.

The company is collaborating with Mayo Clinic, which owns an equity stake in the company. Juan Crestanello, a cardiovascular surgeon at Mayo, said he and his colleagues have seen some of Medical 21's work.

"The results, so far, have been very encouraging," Crestanello said. If clinical trials proceed, Mayo would be interested in being a trial site.

And while Villafana has found great success, he's also failed, like many serial entrepreneurs do. Medical 21 is his third consecutive company aimed at improving bypass surgery. CABG Medical Inc. developed an artificial graft, but shut down in 2006 after unsuccessful clinical trials. And Kips Bay Medical created a mesh designed to support natural vein grafts. That company shut down in 2015.

Ward, of Cardiovascular Systems, believes Medical 21 may ultimately succeed where others have failed because of its persistent leader.

"Manny never moved on," Ward said. "He just keeps at it. He's going to keep working on it."

UnitedHealth shareholders give tepid support to $60M in stock-based pay for new CEO

Target recalls more employee groups to downtown Minneapolis headquarters

Ronzoni pasta-maker coming to Lakeville in $880 million Post acquisition

$200M acquisition by Minneapolis company will help it aid other firms make deals