Did St. Paul really protect gangsters during the Prohibition era?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

The walls of the former federal courthouse in St. Paul are adorned with photographs from a notorious time in the capital city's history, when famous gangsters stood trial in the building.

But those black-and-white pictures from the 1930s — hanging in what is now Landmark Center — tell only part of the story about St. Paul's role in organized crime. Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's community reporting project fueled by great reader questions, dug deeper thanks to this question from an anonymous reader:

"During Prohibition, did St. Paul really agree to welcome gangsters into the city as long as they committed their crimes somewhere else?"

Not only was St. Paul known as a safe haven to the most violent and vile crooks in America for more than 30 years, but it was widely considered to be the "second most corrupt city in America outside Chicago," said Paul Maccabee, author of "John Dillinger Slept Here."

It was all thanks to something known as "The O'Connor Layover Agreement." But St. Paul's reputation as being more than a little friendly to bad guys didn't start that way at all.

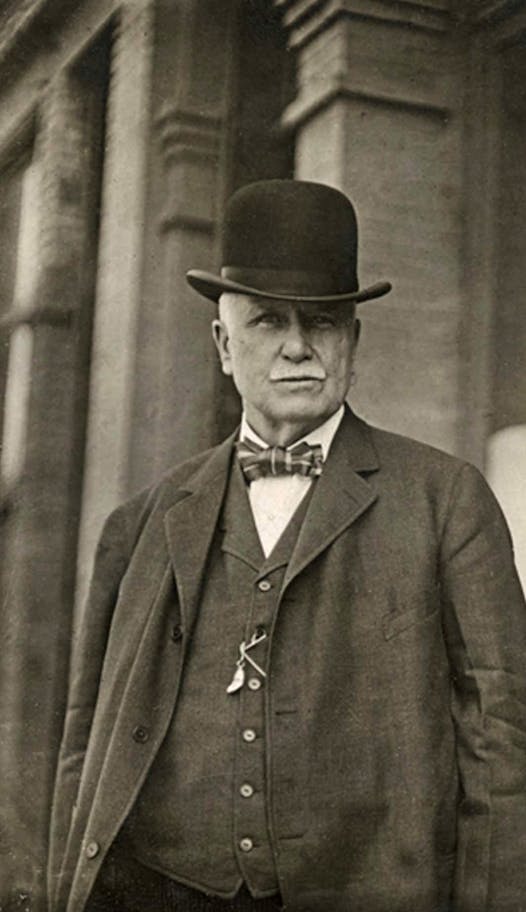

In the early 1900s, police chief John J. O'Connor started dispatching squads of sharp-eyed detectives and police officers to Union Depot to scan the faces of passengers getting off hundreds of trains daily, said Ed Steenberg of the St. Paul Police Historical Society. When a known criminal was spotted, the police not-so-gently put them back on a train headed out of town.

For a while, it worked pretty well and O'Connor won praise for keeping crime low in the saintly city. But corruption soon got in the way.

"It was a slippery slope," Steenberg said. "At some point in time, maybe the mayor said, 'That guy's a friend of mine.' Or some judge said, 'That guy's a friend of mine.' ... And, at some point in time, there were financial transfers made."

He added: "Whether [the payment] was to the judge or to the mayor or to some go-between, some of it ending up possibly in John J. O'Connor's purse, we really don't know."

Before long, the police simply looked the other way as gangsters came to town, Maccabee said, provided cash was paid upon entry at the depot or, later, at a room on the third floor of the St. Paul Hotel.

"You could kill somebody in Minneapolis, you could rob a bank in Des Moines, you could do whatever crime that you wanted. But as soon as you came to St. Paul, no one could touch you," Maccabee said. But crime committed in the city had its consequences.

"If you were caught snatching jewelry from around the neck of a woman on the streets of St. Paul, the police didn't arrest you but took you up to O'Connor's office where they beat the crap out of you and you limped out," Maccabee said. "And you thought twice about snatching a necklace in St. Paul."

The public didn't seem to mind the arrangement, referred to as the "Layover Agreement" because the criminals were "laying over" in St. Paul.

"The amazing thing about the O'Connor system is that everybody knew it," Maccabee said, pointing to a mention in the city's 1904 police year-end report. "It says at the end, as a result of the O'Connor system, 'Never in the history of our city have the people of St. Paul been so safe.'"

Growth of organized crime

Ironically, the system bearing O'Connor's name really took off when he retired in 1920 and Prohibition fueled the explosion of organized crime. As long as liquor was illegal, criminals, booze and cash moved freely through St. Paul. But when Prohibition ended in 1933, gangsters had to find other ways to make a living — and the cops assisting them got involved in some major crimes.

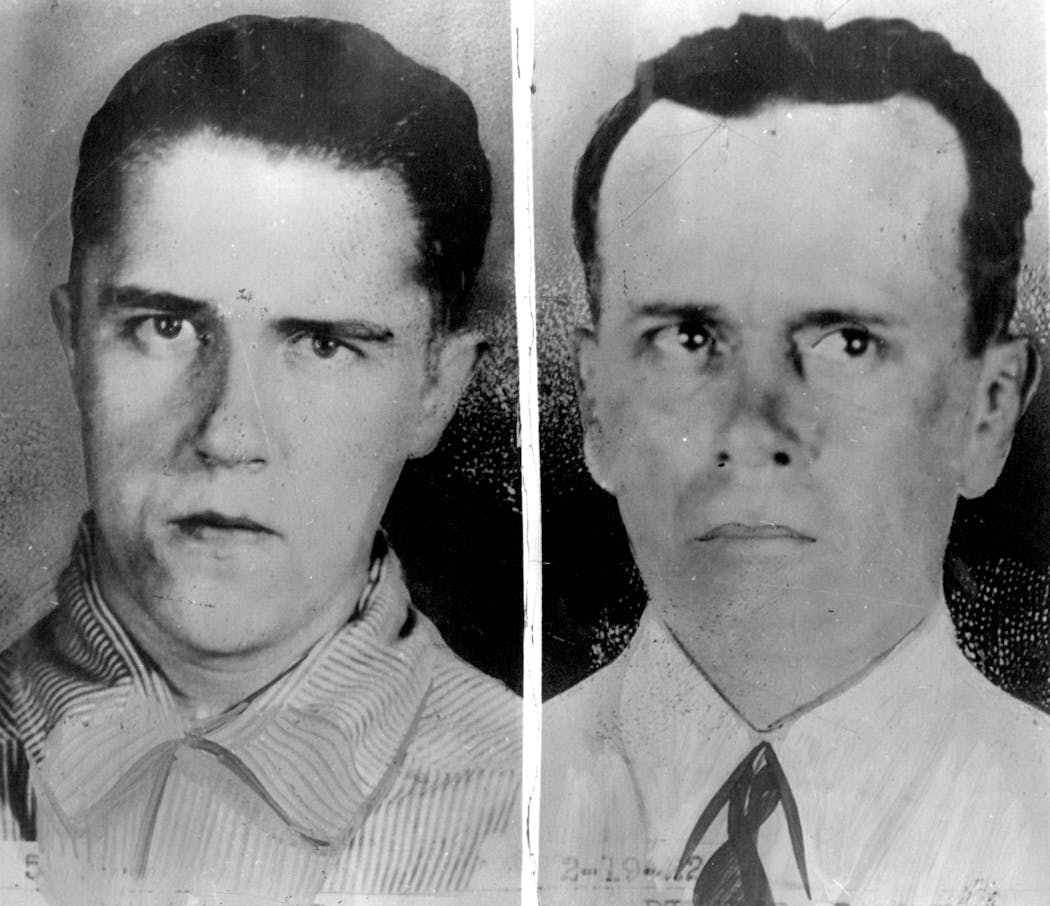

Some gangsters robbed banks. People like John Dillinger, Homer Van Meter, "Machine Gun" Kelly, Alvin "Creepy" Karpis, Ma Barker and her sons Fred and Doc as well as "Baby Face" Nelson all spent time hiding out in St. Paul after bank robberies. Cops even tipped off Dillinger and the Barker gang about impending raids in time for them to escape.

High-profile kidnappings pushed the envelope too far, however. The 1933 kidnapping of brewer William Hamm and the 1934 kidnapping of banker Edward Bremer — both in St. Paul — ultimately fractured the O'Connor system, Maccabee said. Once it became clear that the wealthy of St. Paul were no longer safe, the call for change grew louder.

And after the St. Paul Daily News hired a former cop to tap police headquarters phone lines and the newspaper published the transcripts, the time came to clean out the corruption. At least nine police officials were suspended or fired after an investigation in 1935, Steenberg said.

Onetime Police Chief Thomas Brown, who together with three other cops had gunned down Van Meter in 1934, was booted from the force in 1936. He had been investigated for tipping off Dillinger and the Barker-Karpis gangs and was later found to have aided and abetted the kidnapping of Hamm and Bremer.

St. Paul Police Chief Todd Axtell said it's important for the police department to understand its history, and the importance of transparency. While the O'Connor Layover Agreement may have started as a way to prevent crime, it led to years of abuses — which in turn led to a number of reforms.

"One lesson learned was if you lie down with dogs, you wake up with fleas," he said.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why was I-94 built through St. Paul's Rondo neighborhood?

What kind of police training do cops receive across the state? Is there one standard?

Why do inland cities like St. Paul have so many seagulls?

How many WPA projects were built in Minnesota as part of FDR's New Deal?

Did Ford make millions of windows from sand mined beneath its plant?

Why do tiny cities like Lauderdale, Landfall, Lilydale, & Falcon Heights exist?

Correction: St. Paul Police Chief Todd Axtell was incorrectly quoted in a previous version of this story.