EAGLE PASS, TEXAS

A handgun used in one of the worst mass shootings in St. Paul history began its journey to Minnesota from here, in a sprawling blue factory near the Rio Grande.

Like every Mossberg MC2c pistol, No. 017520MC wears its birthplace stamped along its 4-inch barrel. Its maker, best known for shotguns, bet this new line of 9mm handguns would help the century-old family business break into the booming self-defense market.

"Trouble is unpredictable," O.F. Mossberg & Sons Inc. cautioned while announcing the pistol. "It arrives without warning, when and where you least expect it. So be prepared."

Safety is exactly what the final owner of 017520MC said he wanted when he sent a volley of bullets into a crowded St. Paul bar. By the time police arrived, a young woman lay dead and more than a dozen gunshot victims were pleading for help.

The story of this pistol's short, violent life, compiled from hours of interviews, hundreds of pages of court documents and review of surveillance and police body camera footage, is like that of thousands of legally purchased handguns that turn up in crimes across Minnesota each year.

Though assault-style rifles have captured the attention of lawmakers and gun control advocates, 017520MC is far more representative of what's behind the steady rise of bloodshed sweeping across the country. Handguns, first bought legally, are most frequently the firearm of choice in the surging rate of gun homicides in Minnesota and nationally.

Of the nearly 300 fatal shootings in Minnesota between 2021 and 2022, vastly more were specifically attributed to handguns than rifles or shotguns. And people injured but not killed by gunfire is at historic levels around the state — up 176% last year from 2019.

Police in Minnesota continue to retrieve a record number of guns from crime scenes. And pistols, mostly 9mm, are nearly always the gun they find.

Three flags — Mexico, United States and Texas — fly in front of the sprawling Maverick Arms plant, which faces a craggy hillside bluff and is backed up near a tall, rust-colored border fence.

The steady hum of production droned one recent evening, and flatbed trucks tore out of surrounding lots. Just outside the industrial park, families gathered at youth soccer and baseball fields to watch their kids play in the muggy night. Traffic stood still on the bridge into the U.S., and migrants waded through river waters in search of asylum.

Neither man-made nor geological barriers can separate the shared culture of Eagle Pass, which is 97% Latino, from its Mexican sibling, Piedras Negras.

But a single sign at a bridge checkpoint marks a clear distinction.

"NOTICE: Guns are illegal in Mexico."

Guns are plentiful on the Texas side of this divide. They've been churned out around the clock for more than 30 years, ever since Mossberg started producing firearms in this city of 29,000.

"That was a turning point for Eagle Pass," said Morris Libson Jr., who leads the Eagle Pass Maverick County Economic Development Alliance.

Today, nearly all of O.F. Mossberg & Sons' guns are made in Eagle Pass. The Connecticut-based company joined an ongoing trend of gun makers moving their business from blue states to places perceived as more friendly to their interests. The state of Texas even chipped in $300,000 toward the company's last expansion.

"Investing in Texas was an easy decision," Mossberg CEO Iver Mossberg said at the time, noting that the state "honors and respects the Second Amendment and the firearm freedoms it guarantees for our customers."

Through a spokesperson, O.F. Mossberg & Sons declined to comment for this article.

Within this barbed wire-enclosed building, Mossberg in 2019 made its first pistol in a century: the MC1. The MC2c followed about a year later, billed as a bigger, higher-capacity version capable of firing up to 17 bullets — more than double its predecessor.

Gun merchants in the city say residents have been stocking up on pistols since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and amid anxieties about illegal immigration. Nationally, FBI background checks for gun sales soared to an all-time high of 39.7 million in 2020 and have remained above 30 million each year since — well above pre-pandemic highs. Last year, more than 57% of background checks associated with a specific gun transfer were for handguns.

"Everyone has a gun here in a border town," said Justin Salinas, who opened WarTribe Armory shortly after returning home from the Army.

Yet every Mossberg pistol produced in Eagle Pass leaves the city. Neither the MC2c nor any other Mossberg handgun was on shelves at the Academy sporting goods chain earlier this year. A sales associate there said he hadn't even heard of the pistol. Neither had Salinas.

In the Twin Cities, the line's sales have remained relatively low compared with the bigger pistol brands at stores such as Kory Krause's Frontiersman Sports in St. Louis Park.

"They are not a bad gun, just that they are not very popular in our market," Krause said.

But their compact size, capacity and price appealed to customers whose criminal histories barred them from buying the guns legally. Associates without criminal records instead did the gun-shopping, turning a profit in the process.

Back in Minnesota, Jerome Horton Jr. crisscrossed the metro area during the summer and fall of 2021, on a shopping spree for handguns. He bought 33 in all, spanning multiple brands but all the same caliber. Two dozen of the guns, including 017520MC, were purchased at Fleet Farm stores in Blaine and Lakeville.

The 26-year-old Minneapolis man paid cash, around $400 or more per pistol. Surveillance cameras and sales clerks sometimes observed him on the phone, debating what to buy with others who waited outside the store.

Minnesota imposes no limit on the number of pistols or semiautomatic military-style assault weapons that can be acquired by residents with valid permits. But anyone who obtains a gun on behalf of someone ineligible to possess one can face federal or state charges.

Horton was not buying them for himself. He was working with Gabriel Young-Duncan, 27 of St. Paul, to funnel his guns to buyers with criminal histories. The practice, known as straw buying, can be lucrative. The original seller can make a profit of $100 or more for each gun they divert to the black market.

Police later linked some of the pistols Horton bought to other crimes around the metro area, and a 6-year-old found one discarded in his family's north Minneapolis front yard. Most of the guns remain unaccounted for.

Straw buyers cannot know "what type or what level of chaos and misery that those firearms are going to inflict on communities," said Assistant U.S. Attorney Thomas Calhoun-Lopez, who prosecuted Horton and Young-Duncan.

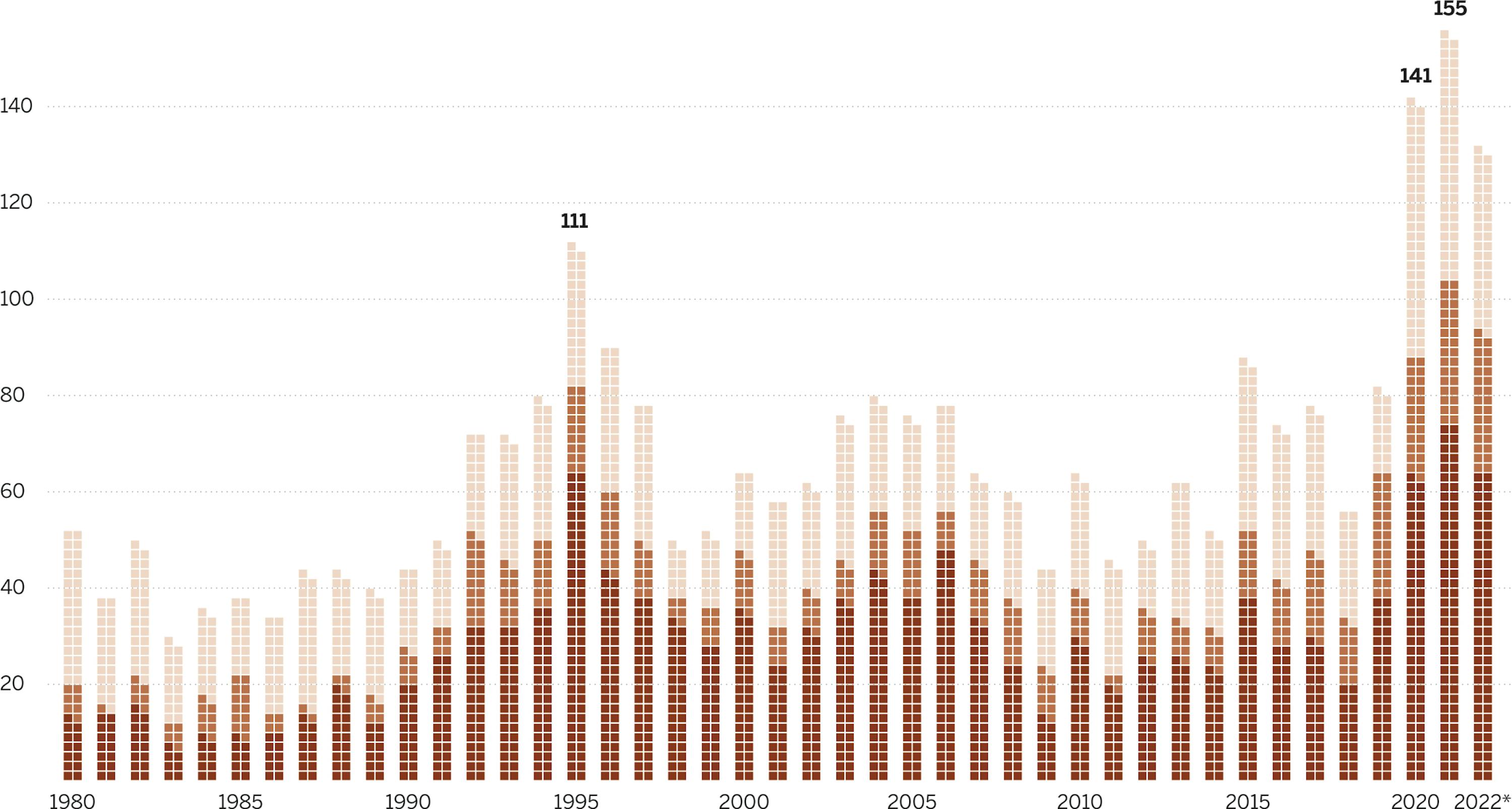

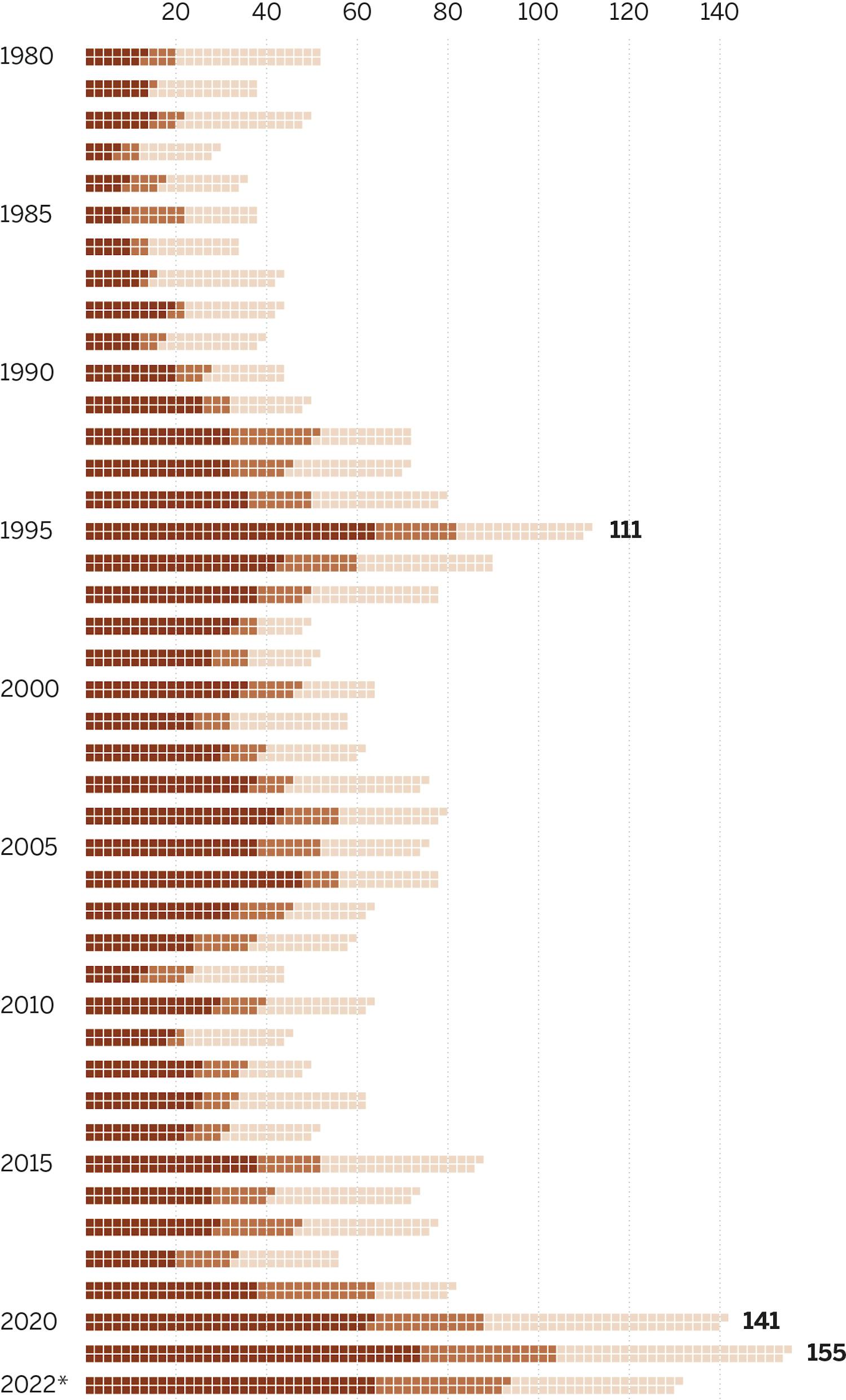

Fatal shootings in Minnesota

Gun homicides in Minnesota have surged to record levels since 2020, reaching rates and volumes not seen since the 1990s.

Yuqing Liu, Star Tribune

Numbers include murders and non-negligent homicides, mostly involving handguns.

2022 numbers from outside the Twin Cities are preliminary.

Yuqing Liu, Star Tribune

Numbers include murders and non-negligent homicides, mostly involving handguns.

2022 numbers from outside the Twin Cities are preliminary.

Devondre Phillips' plane touched down in the Twin Cities just before 10 p.m. His cousin waited for him outside the terminal that warm October night and suggested they grab a drink before heading home. He soon navigated to St. Paul's W. 7th Street, which is lined with popular bars and restaurants.

Phillips, who split his time between Las Vegas and his native St. Paul, had cut short his previous visit to his hometown that summer. An argument with his cousin's boyfriend, Terry Brown, escalated quickly. The conflict started when Phillips intervened in an argument between his cousin and Brown. They exchanged words before taking their dispute outside. Brown drew his gun. Phillips also had a gun, but was disarmed by another man.

"Why did you carry a gun that summer?" defense attorney John Lesch later asked Phillips before a jury.

"I figured it would be better safe than sorry," Phillips said, citing an uptick in violence in his family's neighborhood.

No shots were fired that night, but Phillips said he started receiving threatening messages in the following days. He abruptly left for Las Vegas after someone shot at his car. When he returned several months later, he was unarmed.

But not for long.

Walking to the bar on W. 7th, Phillips noticed an old friend from high school and stepped aside to chat.

The friend, whom Phillips said he knew as "Mo," was surprised to see Phillips. He'd heard of the summer altercations and asked if his buddy was armed.

"No, I'm not," Phillips replied.

Mo told him that he happened to be getting rid of something Phillips might want: a 9mm pistol. Phillips handed over $600 and became 017520MC's newest owner. He later admitted in court that he knew the gun was fully loaded as soon as he gripped it. He chambered a round and tucked the gun in his waistband before rejoining his group as they walked into the crowded Truck Park bar.

Andrea Weathersby spent more than a year depressed and shut in after her mother died in a car crash. But Weathersby, a 34-year-old hairstylist from St. Paul, said yes when her sister asked her to come to the Truck Park bar.

"I was out trying to get myself used to being around people again," she said.

She felt safe, she said, upon seeing security staff. She danced and laughed with her boyfriend and her sister near the bar.

Not far away, Phillips locked eyes with Brown, Allen Walker and Jeffrey Hoffman — the same three men whose threats and altercations prompted his earlier retreat to Las Vegas.

At 12:16 a.m., Phillips stationed himself in a corner near the bar's indoor food truck and soda machine. Hoffman approached.

Phillips later claimed Hoffman told him, "Caught ya. You're dead." Hoffman said he merely said, "What's up?"

Surveillance footage from the bar doesn't capture what was said, but within 5 seconds, Phillips fired two rounds from 017520MC into Hoffman's body.

The clap of those first shots sent nearly all of the roughly 100 people inside the bar ducking to the ground or scrambling for cover. Several leapt over the bar and others jumped through a front window to escape.

Phillips walked toward Brown, who raised his own pistol. They fired at each other from just feet apart. Both men hit their targets: A broken right leg sent Brown crumpling to the floor under his own weight. Phillips was crawling by the time he reached the exit, his femur shattered and leg bleeding from a severed artery.

But the guns fired by Phillips and Brown did not discriminate. In a span of 10 seconds, they shot another 13 people.

Marquisha "Kiki" Wiley, a 27-year-old vet technician, died almost instantly after a bullet fired by Brown pierced her heart and lung.

Others struck by 017520MC included a man shot in the Achilles tendon as he tried to find cover behind the bar area. One bullet went through two friends' legs; only one knew she'd been hit. The other only realized she'd been shot when she arrived at the hospital with her friend.

Two other people were shot in the right arm, including a man who later lost an artery. One young woman had a bullet fragment removed from her arm at the hospital.

Weathersby remembers being dragged to the ground before she heard the shots. Bodies fell and glasses crashed. Drinks splashed all over her.

She was in Phillips' line of fire as he shot his way out of the bar. When a bullet from his gun hit her, it felt like a hammer crashing down on her foot.

Weathersby braced for more bullets as panic set in. She felt trapped and couldn't peel the bodies away to escape. In those frantic moments, she thought another patron was using her as a human shield. More than a year later, seeing footage of the shooting during Phillips' trial, Weathersby realized the man used his body to shield hers. He absorbed a round in the leg and survived.

Weathersby soon broke away and stumbled out of the bar, crying out for her sister and boyfriend. She saw Wiley's body, and others who had been wounded.

She knew she had to call the police, but her panic didn't allow her to remember the number. She tried 311 and 411 before finally dialing 911.

A police squad car arrived 3 minutes after the first shot rang out.

"Do you guys see anybody with a gun?" St. Paul Police officer Joshua Needham asked.

"I can't breathe!" Weathersby shouted as her sister applied pressure.

"Stay put, I have to figure out who else has been shot," Needham said.

Moments after the last shots rang out, a patron pounced on Brown, pummeling and trying to disarm him before security intervened.

Outside the bar, Phillips rose to one leg and hopped toward a Honda Civic. He briefly crawled inside before tumbling backward on the street in a futile attempt to stand. When police found him, bystanders were trying to stop the blood gushing from his leg.

It didn't take long for police to find 017520MC. The butt of the pistol, red with blood, poked out from a pouch behind the passenger seat of the car, which police had ordered towed.

St. Paul investigators swabbed for DNA samples, collected fingerprints and test-fired the gun to compare ballistic evidence. They found no link to previous shootings.

The U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) traced 017520MC's lifespan from Eagle Pass, Texas, to Blaine and to Horton, the gun's original purchaser. They discovered that Horton had purchased it and two other 9mm pistols from the Blaine Fleet Farm on the same day.

Days later, ATF agents talked to an employee at Frontiersman Sports in St. Louis Park, who said that Horton had been there that day to buy more guns. Staff at the store suspected that he was a straw purchaser: He had parked his car to avoid surveillance cameras, used a learner's permit instead of a driver's license and made multiple purchases of firearms over two days, paying in cash. When he left the store, Horton waved gun boxes in the air to people waiting outside.

Horton returned to that store hours after a federal agent spoke with its staff, trying to buy another gun. The salesperson intentionally stalled.

When agents searched Horton's home four days later, he admitted to selling firearms to several people. He told agents that he assumed the buyers agreed to pay extra because they "can't get their gun licenses." Young-Duncan later admitted to receiving 017520MC from Horton before passing it along to another, unidentified person.

For two months, the pistol was as anonymous in the streets of St. Paul as it was when it left Eagle Pass. It found infamy within an hour of its final purchase.

Horton and Young-Duncan both pleaded guilty to their charges. They are scheduled to be released next year from the federal prison camp in Duluth, and they are now forever barred from owning firearms.

A Ramsey County jury in February convicted Phillips of eight counts of attempted second degree murder for his role in the October 2021 shooting. In June, a Ramsey County judge sentenced Phillips to 29 years in state prison for eight counts of attempted murder. Wiley's mother spoke before his sentencing, wearing a shirt with an image of Kiki holding a sign that read, "No more silence, end gun violence."

Before jurors convicted Phillips, Assistant Ramsey County Attorney Treye Kettwick used Phillips' own words to describe what 017520MC meant to him when he brought it with him into the bar: "If you've got a fully loaded Mossberg 9mm in your waistband, you don't have to live in fear."

Brown awaits an Aug. 8 sentencing after a jury convicted him of murder in June for Wiley's death and other charges stemming from the shootout.

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison is suing Fleet Farm, alleging that it was negligent in failing to identify and curb Horton's suspicious, frequent gun purchases. The lawsuit is still in its early stages, but Ellison called the case an important step toward choking off the supply of firearms to criminals.

"There's blood on their hands, in my opinion, and they should stand judgment and be held responsible and do better in the future," Ellison said of Fleet Farm.

Fleet Farm did not respond to requests for comment.

The bullet fired into Weathersby lodged in her ankle, cracking it in two. She still can't stand up for long stretches of time, and now does much of her hairstyling while seated. She also repositioned her workstation so she never has her back to a window.

She struggles with crowds, particularly of young men. She'll be out to eat with her boyfriend or children and break down in tears, telling them, "They're about to shoot in here," or "I'm about to get shot."

"I don't think I'm ever going to be the same," she said.

No. 017520MC, dried blood still covering its black frame, will remain stored in the bowels of St. Paul's police headquarters until at least after Phillips' appeals process is done. When it finally leaves the evidence locker, it will be melted down and recycled.

Star Tribune staff writer Jeff Hargarten contributed to this story.

Credits

Reporting Stephen Montemayor and Jeff Hargarten

Photography Leila Navidi, Emily Johnson, Deb Pastner and Reneé Jones Schneider

Videography Matt Gillmer and Jenni Pinkley

Graphics Yuqing Liu and C.J. Sinner

Editing Eric Wieffering and Abby Simons

Design Bryan Brussee, Josh Jones and Josh Penrod