Star Tribune's 2019 Artists of the Year

B

the time you encountered Dyani White Hawk's white-hot work, just inside the first gallery, you'd seen the custom El Camino parked at the show's entrance. With its black-on-black pattern, the car issued a kind of warning: In this show, pottery might not take the form of a pot.

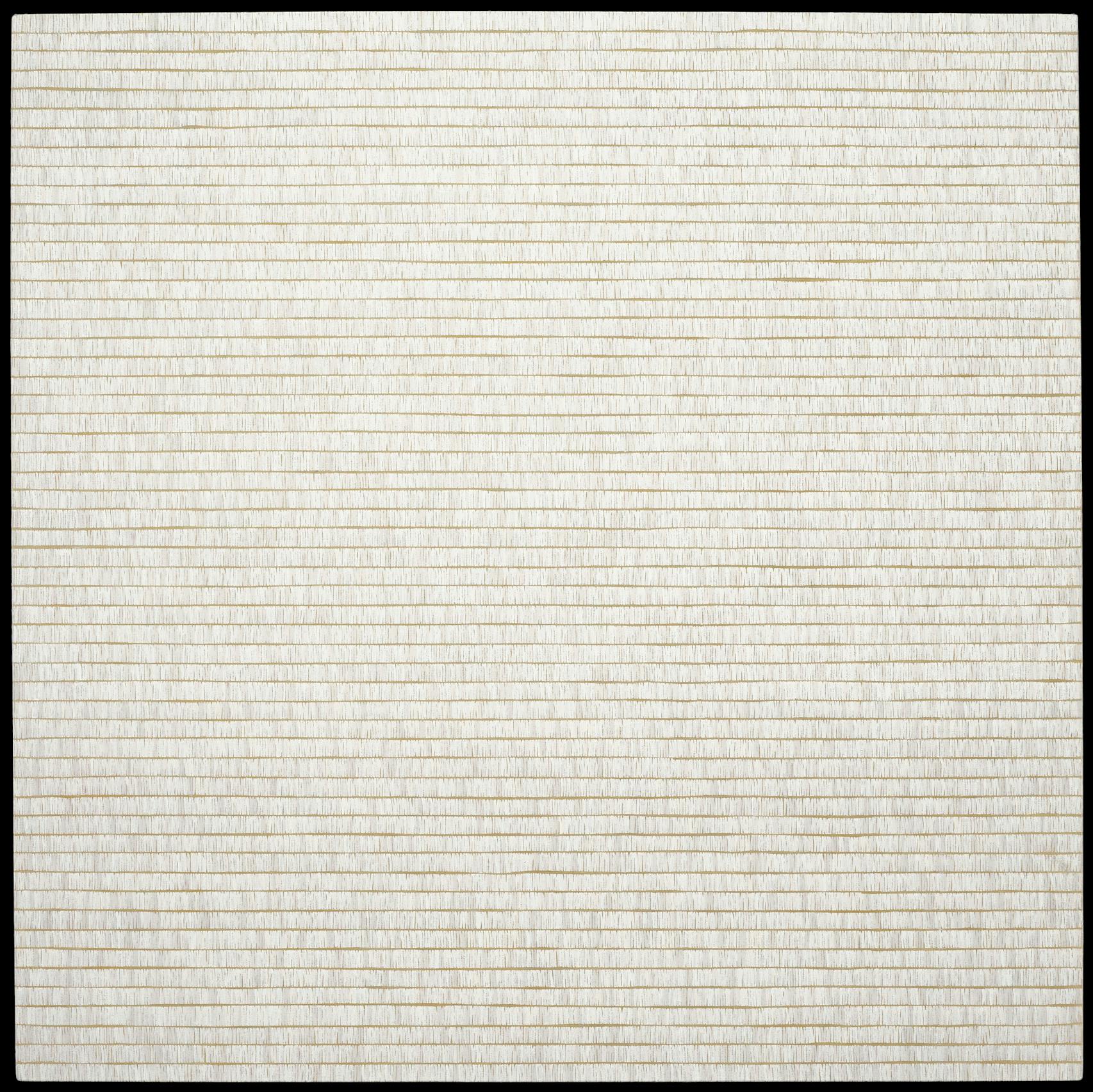

Thusly warned, you might look more closely at White Hawk's painting, the first in her "Quiet Strength" series. Row after row of tiny white brush strokes — quillwork that's not made of porcupine quills.

The influential magazine Artforum declared it the strongest painting in "Hearts of Our People," a Minnesota-born, nationally recognized exhibition that has garnered its own list of superlatives: groundbreaking, once-in-a-generation, a massive undertaking, a starting point for new scholarship. Hyperallergic, an online arts magazine, just named it one of the best art shows of the decade.

Six Minnesota artists — White Hawk, Julie Buffalohead, Andrea Carlson, Heid E. Erdrich, Louise Erdrich and Delina White — created some of the show's defining artworks. They are works that both honor and toy with tradition. Works that challenge and surprise.

These artists, at the height of their powers, are the Star Tribune's Artists of the Year.

Individually, they had a strong 2019 packed with new works, solo shows and high-profile honors. But together, they helped "Hearts of Our People" rewrite history. The touring exhibition, launched in June at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, gathered more than 117 artworks from Native American women spanning centuries and geographies and styles and put them in conversation with one another.

"I had complete faith in the women's voices — the ancient, the current and the ones to come," said the show's co-curator, Teri Greeves. "I know the power these women hold; it's apparent in their work. I knew that once all these pieces came together, that power would vibrate."

The show came together in conversation, too. It was created not by a single, all-knowing curator but by a group of women.

Greeves, a Kiowa beadwork artist, and Jill Ahlberg Yohe, Mia's associate curator of Native American art, gathered an all-female, mostly Native advisory panel of 21 artists and experts. They had a say in every step of the show's creation, from picking artworks to signing off on texts and translations.

To reflect that collective process — and the resulting vibrations — the Star Tribune honors the artists as a group. Employing the consensus of women, a norm in Indigenous communities, to curate a show is "a provocative mandate for museums," Artforum noted.

Louise Erdrich, the famed author who opened her journals for the exhibition, noted that while the show focused on Native women, the work within it went beyond "any sort of categorizing ... into a realm where art spoke."

'Ou

own voices'

Deep within "Hearts of Our People," a story plays out on paper:

A sly rabbit tempts a young woman by displaying a spoon with a glossy cherry on its tip. Here, in Julie Buffalohead's topsy turvy takedown of the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, the rabbit balances atop "Scaffold," a work modeled partly on the gallows used to hang 38 Dakota men in Mankato in 1862. Her eyes on the cherry, the young woman seems unaware of another rabbit at her knee, a noose tied around its neck.

Buffalohead's drawings, paintings and collages tell tales, and the protagonist of "The Garden" is a coyote. Taking advantage of the misdirection, it coyly glances back, a blue rooster modeled after the Sculpture Garden's "Hahn/Cock" in its mouth.

Buffalohead made the 6½-foot-long work in 2017, soon after protests over "Scaffold" led to national criticism of Walker Art Center and the sculpture's dismantling. The Walker acquired her piece the following year. She wanted to capture what it felt like for Native people to be reminded of a painful history, what it felt like to see that history depicted by a non-Native sculptor.

"Our issues get used in a certain way by different artists," she said in a recent interview. "But our own voices barely get heard. Native people want to be heard in their own voices."

Then-Walker director Olga Viso acknowledged that before erecting the work, "I should have engaged leaders in the Dakota and broader Native communities."

Across town, the Minneapolis Institute of Art had been doing things differently. During a chilly week in November 2014, Native women from across the country trekked to Mia to answer a question: "Why do Native women artists create?"

Ahberg Yohe had dreamed for years of an exhibit of Native women's art and pitched it soon after joining Mia in 2014. But she and Greeves knew that a show of this size and scope would require a roomful of experts. They began by asking each advisory board member to nominate 10 objects they deemed essential to include.

"So you can imagine — 21 people each bringing forward 10 artworks," the curator said. "It took time."

Alberg Yohe, who is non-Native, likes to tell people this process couldn't have happened anywhere but Mia. That doesn't mean it was easy.

"People would say, 'You can't have 21 people and make a cohesive story.' 'You can't reach consensus.' Well, we did. Yes, you can. All the stuff that everybody said was too much was at the core of the show's strength."

Typically, a curator — probably white, probably male — has an idea for an exhibition of Native art, Greeves said. He brings in a few Native Americans for a day or two, "treats us really well." The group comments on works already selected. The curator scribbles notes and makes no promises. "Then you never hear from them again," she said. "I started to think, 'What the hell is this? What are they using me for?' "

Creating "Hearts of Our People" took five years and thousands of e-mails.

From the beginning, it felt different, said Heid E. Erdrich, a Minneapolis-based writer and artist. "This wasn't jockeying for whose vision was going to eclipse everybody else's," she said. "It was more about finding a thread in what we were all weaving together."

Now on view at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, "Hearts of Our People" will travel in February to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and in June to Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Okla. The show acts as a correction, naming and uplifting artworks made by women who have for too long gone unnamed and overlooked. By pairing old and new works, it points out the traditional in the contemporary — and the innovation in the traditional.

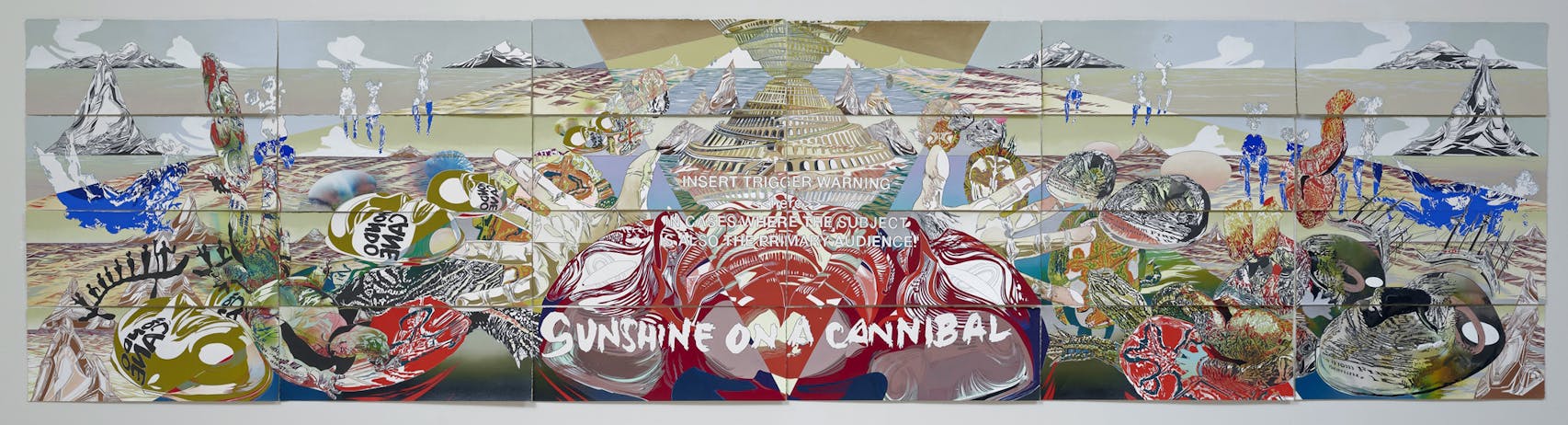

In a room lined with beaded bags and dresses, Carlson's trippy, 15-foot landscape posed tough questions about the way popular culture exploits Native culture. The drawing layers a flurry of images — seascapes and petroglyphs, painted turtles and a headless baby doll — from films and artworks, interrogating the beliefs behind them.

"I don't utilize a lot of traditional forms. I don't make a lot of references to my Ojibwe-ness," said Carlson, 40. Some references are tucked into the work, "but you have to squint to see them. You have to know what you're looking for."

The show's combination of new and ancient works illustrates "how contemporary artists are still sourcing their Native heritage but in a very different way," said Buffalohead, 47, a member of the Ponca tribe of Oklahoma who was born and raised in Minneapolis.

It's striking, still, to see a show focused on Native American women, she said. "A lot of times, especially in the contemporary art world, Native women tend to get ignored.

"But that's something that's happened in history, too: We pay a lot of attention to men and warriors and chiefs."

'A

long chain of greatness'

Between the paintings and the sculptures were words. Poems and songs. A journal, cracked open.

A poem by Heid E. Erdrich set to video — a "poemeo," as her niece dubbed the form — looped in the first gallery. It was inspired by the English/Ojibwe dictionary's entry for clouds, which is two full pages long.

"I was trying to imagine what it would be like to have a worldview where there were so many words for clouds," said Erdrich, 56, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe.

Many of the writer's contributions were less visible: Along with White Hawk, she served on the advisory board, helping to collect the show's poetry and song. She wrote for the show's catalog, a hefty, 350-page volume. Then, a week before the show, she and her family members folded more than 400 tobacco ties that visitors could carry as a comfort or leave behind as an offering.

"I wanted our voices in there," Erdrich said. "Everything we do is with song. Those beautiful dresses don't exist without music, without a song. And the contemporary version of that is literature."

In video interviews within the exhibit, artists often speak about — and sometimes sit beside — their mothers and grandmothers. The works, too, acknowledge that ancestry, nodding to traditions and to spirits.

"That's something I think sets it profoundly apart from the Western, masculine past of so many art institutions," said Heid's sister Louise, 65. "So many of these works went beyond this particular time to point to the ancestors whose traditional teachings came through the particular artist."

That doesn't happen with the men heralded by the art world, she noted. "You don't find Chuck Close saying, 'I learned this from my family, including the generations before.' Saying, 'I'm a temporary carrier of this talent.' But that was a huge part of this exhibit."

Delina White was 6, living in a two-room, tarpaper shack on Leech Lake, when her grandmother taught her how to bead. Today, at 55, she riffs on woodland floral patterns rooted in her Anishinabe heritage, designing beaded bandolier bags.

But the curators were interested in an 1800s design White re-created from an old book: a thunderbird for her son, a dancer whose Native name means "lightning going around in a circle."

"I wanted to make sure he has that connection to his clan and to his relatives," she said.

The beading is intricate, traditional. White, an enrolled member of the Minnesota Chippewa tribe, also plays with form. This summer, her label I Am Anishinaabe staged a fashion show at the Walker Art Center for a new line of gender-fluid clothing, including ribbon shirts rather than skirts, for people who identify as Two-Spirits, or nonbinary.

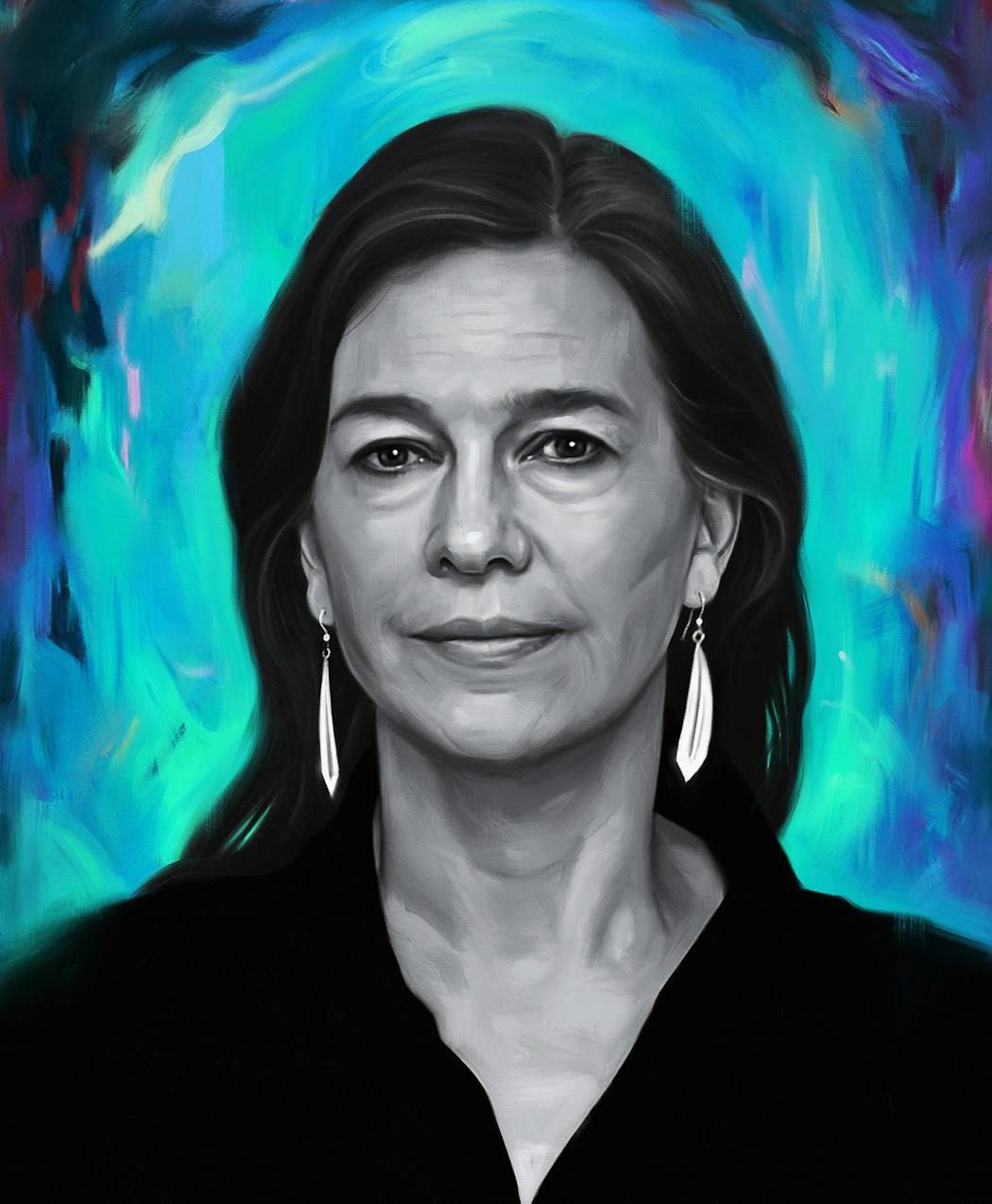

White Hawk, 43, beaded her canvases for years, forming abstract arches that might be moccasins, doors or both. Her newer, bigger works mimic Lakota beadwork and quillwork with tiny, vertical lines that create subtle and strong geometries atop layers of metallic paint.

Studying art, she was drawn to abstract painters such as Marsden Hartley only to discover, in their biographies, time spent with or near Native communities. White Hawk argues that Native women shaped modern abstraction, titling a solo exhibit this year "See Her." That show, at the Lilley Museum in Reno, earned her another Artforum nod as a top pick for 2019.

Like the exhibition at Mia, her works rearrange the hierarchy, "recognizing the legacies of Indigenous women to the history of abstraction and to women at large to the history of abstraction," White Hawk said. "Because both are overlooked and undervalued."

Walking through "Hearts of Our People" for the first time, White Hawk was moved — "I just basically tried not to cry all over everybody" — witnessing eight galleries full of hundreds of years of women's artworks relating to one another.

"You get to physically see that continuum," she said. "It's a really humbling experience to recognize that you're one link in this extremely long chain of greatness. It's beautiful."

HONOREES

Beyond "Hearts of Our People," their lives have often intertwined. Three were part of a show this fall at Highpoint Center in Minneapolis. Andrea Carlson and Heid Erdrich, who have collaborated for a decade, spoke recently at Macalester College about decolonizing museums. They promote each other's work. They wear each other's jewelry. During a photo shoot at Mia, Carlson was sporting earrings Erdrich had given her. Erdrich, in turn, wore earrings designed by Dyani White Hawk and a necklace her sister Louise made for her in her teens.

Julie Buffalohead

Artist of the year

Who: St. Paul artist working with paper, paint and collage.

Her power: Using animals, tricksters and other characters to tell tragic and wryly comedic stories.

What a year: She won a prestigious Guggenheim Fine Arts Fellowship. Her work was part of "Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art" at the Yale University Art Gallery, the group show "Stretching the Canvas" at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, and "Mni Sota Makoce" at Highpoint. She recently unveiled new, large-scale works in a solo show at Mia.

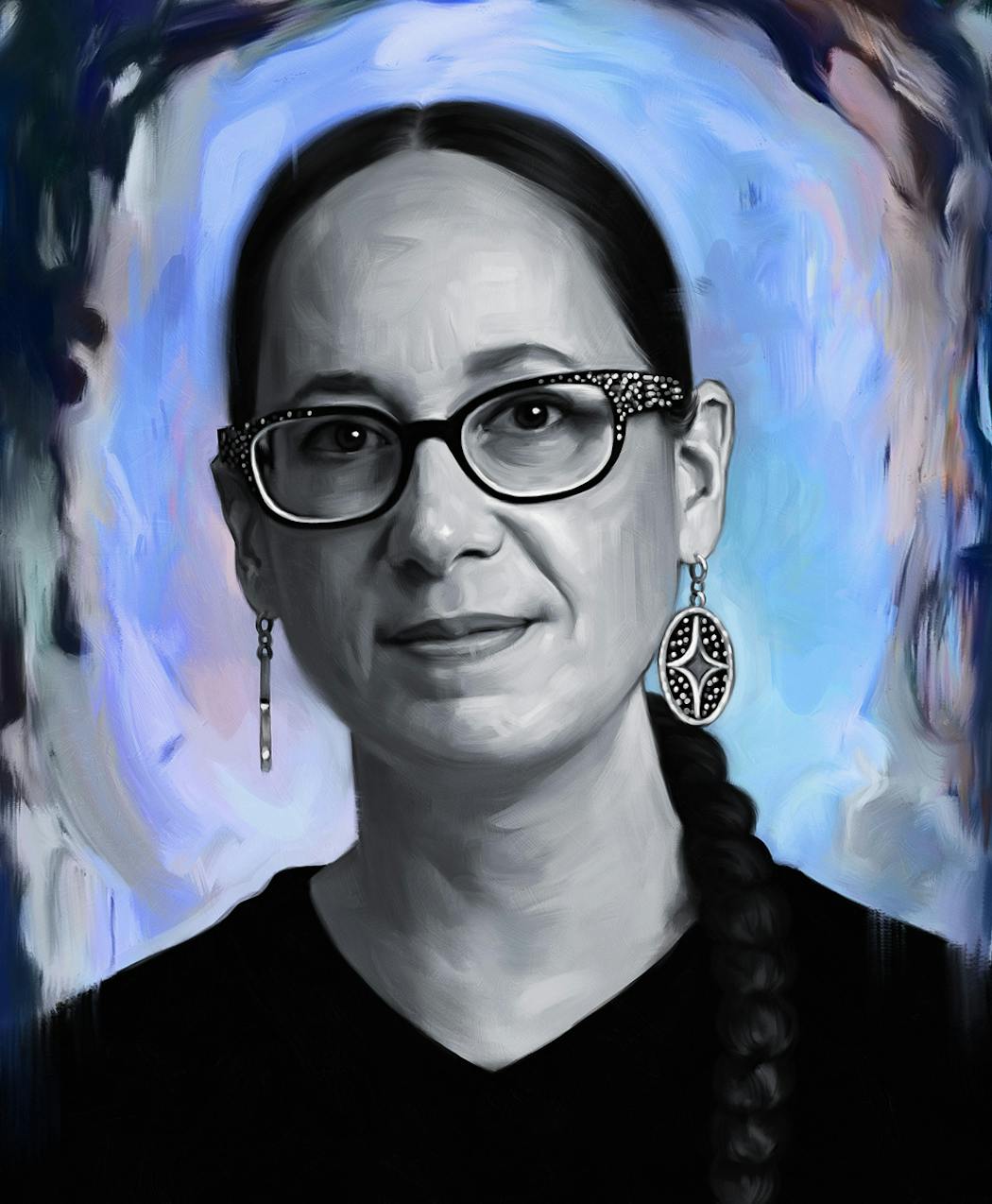

Andrea Carlson

Artist of the year

Who: Artist working with acrylic and oil paint, watercolor, gouache, pen and ink. Currently in Chicago.

Her power: Dismantling cultural stereotypes within movies and museums through her layered landscapes.

What a year: She was part of "Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now," currently at Duke University's Nasher Museum. Her prints were included in "Mni Sota Makoce."

Heid E. Erdrich

Artist of the year

Who: Author, curator and interdisciplinary artist. Lives in Minneapolis. Currently teaching at the University of Minnesota, Morris.

Her power: Crafting poems and editing collections, including last year's "New Poets of Native Nations."

What a year: She was among five poets who won the 2019 National Poetry Series, an honor that includes a $10,000 prize and publication; Penguin Press is set to release her "Little Big Bully" in 2020. In May, she was featured in "Skew Lines," created with Rosy Simas for Soo Visual Arts Center in Minneapolis.

Louise Erdrich

Artist of the year

Who: Legendary author of novels, poetry and children's books. Lives in Minneapolis, where she owns Birchbark Books & Native Arts.

Her power: Telling powerful stories with lyrical prose.

What a year: The New Yorker published her poem "Passion" this month and her short story "The Stone" in September. She also finished work on her next novel, "The Night Watchman," which Entertainment Weekly and others have named one of 2020's most anticipated books.

Delina White

Artist of the year

Who: Apparel designer and beadwork artist. Lives in Onigum, Minn., on the Leech Lake Reservation.

Her power: Translating traditional art forms, including beadwork, into wearable fashion.

What a year: White won the Five Wings Arts Council Master Artist Award, given to one artist biannually. She staged a fashion show at the Walker Art Center in June, and was included in the Haute Couture Fashion Show at the Santa Fe Indian Market. She also partnered with well-known Swedish designer Gudrun Sjödén on a line of bags and dresses.

Dyani White Hawk

Artist of the year

Who: Painter and mixed-media artist working with beadwork, porcupine quillwork and other materials. Lives in Shakopee, works in Minneapolis.

Her power: Combining modern abstract painting with traditional Lakota art forms to comment on those artistic histories.

What a year: Her first major solo show, "See Her," opened at the Lilley Museum in Reno, Nev. She, too, was part of "Mni Sota Makoce." She created a suite of screenprints for Highpoint Editions. She won a ton of fellowships: She was selected as a USA Fellow, with a $50,000 award; a Jerome Hill Artist Fellow, and an Eiteljorg Contemporary Art Fellow. She also nabbed a 2019 Forecast for Public Art development grant.

RUNNER-UPS

Sam Bergman

Runner-up

He plays viola in the Minnesota Orchestra, but that is just the start of it.

In 2019 he plowed substantial energy into developing Outpost, an innovative concert series combining chamber music by living composers with performances by Minnesota actors, poets and storytellers. A collaboration with the Moving Company produced "The Prodigious Life of Clara S.," a play with music about Clara Schumann. Meanwhile he continued the orchestra's "Sam and Sarah" series, with spoken narrations that contextualize pieces conducted by Sarah Hicks.

The common thread? Bergman's passion for demystifying classical music, and making it more accessible.

That mission will continue in 2020, he says. The next Outpost concert — featuring fellow runner-up Kao Kalia Yang — is Jan. 11 at the Hook and Ladder Theater. And on Feb. 2 he plays "an amazing string quartet" piece, "Carrot Revolution," by Gabriella Smith, in an Orchestra Hall chamber concert. "The work I'm doing now is mainly about finding ways to showcase as many diverse and talented performers as I can fit on a stage, and bring their work to new audiences that need to see it," he said. "And in the Twin Cities I am utterly spoiled for great collaborators."

By TERRY BLAIN / photo by TRAVIS ANDERSON

Chris Larson

Runner-up

He had a big year, but for reasons that aren't necessarily about him. "For the last couple of years I've felt an urgency to be more active," he said. "I'm thinking more about the role of artists in society and how it will impact what tomorrow looks like."

He and his wife, Kriss Zulkosky, opened Second Shift Studio Space, a residency program for female and gender-nonconforming artists. He created three massive sculptural reliefs for the Palace Theatre modeled on collages by his late friend, Hüsker Dü drummer Grant Hart. He helped produce three records for Lori Barbero's Awesome Rocker Girls project, and publishes the Twin Cities art quarterly InReview.

"I think these are things you have to show up to experience," he said. (Larson is not on social media.)

Plus there was his own work, including a solo show at Burnet Fine Art and an ongoing project in an abandoned garment factory in Smithville, Tenn., funded by a $55,000 Guggenheim Fellowship. During a recent visit, he created a cacophony of color by tying thread from the old sewing machines to the walls. In 2020, he'll continue rediscovering the factory, and the lives of the people who worked in it.

By ALICIA ELER / photo by JERRY HOLT, Star Tribune

J.S. Ondara

Runner-up

"I knew I would have a lot of expectations for the first record I put out, so I wanted to get all the cards right," J.S. Ondara told us back in January. At year's end, it's safe to declare that the Minneapolis-based singer/songwriter scored a winning hand.

A Kenya native who famously emigrated to Minnesota in 2012 largely out of his love for Bob Dylan, Ondara wound up earning raves from Rolling Stone and NPR, tour dates with Neil Young and finally a Grammy nomination with his 2019 album, "Tales of America." And yes, it's just his first.

Now 27, the earnest, shimmering-voiced troubadour initially gained attention in his adopted hometown under the moniker of Jay Smart and a similar guise singing other people's songs. Turns out, though, he was just saving up his own songs for the right time. That came when the legendary Los Angeles label Verve Records signed him up.

Recorded with help from Andrew Bird and members of the band Dawes — hence the Grammy nod being in the Americana category — "Tales of America" boasts rich but concertedly light instrumentation, letting Ondara's voice and lyrics shine, front and center. Many of the songs are based on his experiences in acclimating to the United States, from the opening prayer "American Dream" to the pop-culture-harried "Television Girl."

Just as many, however, are simply about girls, who can be as elusive as the American Dream in Ondara's eyes. Well played, young man.

By CHRIS RIEMENSCHNEIDER / photo by AARON LAVINSKY, Star Tribune

Rosy Simas

Runner-up

Her extraordinary year began in January with the premiere of "Weave," an enveloping and sensorial work of dance, images and sound that started in the lobby and then filled the stage at the Ordway. It followed an extensive process of engaging with communities and holding open rehearsals, resulting in a vivid work that tingled with a synaptic spark.

Her company, Rosy Simas Danse, took "Weave" all over the country, including Pennsylvania, Alabama and Hawaii, tailoring the presentation to each place and its people. They brought it back home in June for an outdoor performance at the Northern Spark Festival that included a haunting, sculptural procession along E. Franklin Avenue.

"It's always remarkable to watch Rosy work to form the large connections that she does ... with profoundly deep engagement within communities," remarked her longtime collaborator Heid E. Erdrich.

She and Erdrich were artists in residence at SooVAC Gallery in May for "Skew Lines," which drew on her own lineage as a Seneca woman. Simas also continues to use her platform for fearless truth-telling and advocacy.

By SHEILA REGAN / photo by DAVID JOLES, Star Tribune

Michael Starrbury

Runner-up

He proved you can be a major television player and still call Minnesota home.

The veteran screenwriter's contributions to the Netflix miniseries "When They See Us," a dramatization of the Central Park Five case more frightening than any Stephen King novel, earned him accolades and improved the odds that he'll finally make his directorial debut.

He and his collaborator, series creator Ava DuVernay ("Selma," "A Wrinkle in Time"), shared an Emmy nomination for the harrowing and heartbreaking finale. They didn't win, but Jharrel Jerome's portrayal of the wrongly accused Korey Wise beat out Oscar winners Sam Rockwell, Benicio del Toro and Mahershala Ali for best actor in a limited series. It's impossible to imagine such an upset without Starrbury doing the part justice from the upstairs office of his Brooklyn Park house.

"I'm not interested in people telling me I'm great," DuVernay said about her mentee this fall. "I'm interested in people helping me be great."

One gets the sense that we're only beginning to see Starrbury's own greatness.

By NEAL JUSTIN / photo by RENÉE JONES SCHNEIDER, Star Tribune

Laura Stearns

Runner-up

Did anybody reveal their artistry in more ways this year than Laura Stearns? It seems unlikely.

The longtime Guthrie Theater wigmaster retired with a bang(s), going out on two hair-heavy shows: "A Christmas Carol" and "Steel Magnolias," which is set in a salon and required the creation of 1980s wigs that could be styled on stage. Stearns and the wig department have been a huge part of the theater's storytelling, keeping drawers of wigs that fit most of the acting heads in town and researching, for instance, where a character in "The Crucible" would have wounds from being beaten and how quickly his hair would grow back.

Stearns also played the daughter of a woman with dementia in Prime Productions' "Marjorie Prime" at Park Square Theatre, and the mom of a son with autism in Minnesota Jewish Theatre Company's "O My God."

But mostly, she was in the public eye as an activist. She was one of 17 plaintiffs who settled lawsuits against Children's Theatre Company and its instructors as a result of sexual abuse there in the 1970s and '80s, and she started an ongoing series of forums addressing "accountability around the issues of harassment and sexual harm in our industry." In other words, Stearns didn't just do great work in 2019. She's helping the theater community figure out how to make healthier — and, thus, better — work in the future.

By CHRIS HEWITT / photo by GLEN STUBBE, Star Tribune

Kao Kalia Yang

Runner-up

Her first two books came years apart. "The Latehomecomer," published in 2008, was the first book to win two Minnesota Book Awards. Then came "The Song Poet," a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award, in 2016.

But this year the St. Paul writer suddenly is everywhere, teaching us in beautiful ways about the Hmong people, refugees and the lives of people of color. "What God Is Honored Here?," an essay collection edited with Shannon Gibney, was published to national acclaim. Yang's first picture book, "A Map Into the World," garnered starred reviews from industry journals Kirkus and Publishers Weekly, and has already picked up its first award.

Yang delivered her second TEDx talk, helped stage "The Song Poet" at the Ordway, worked on adapting the book for a 2021 Minnesota Opera debut and was honored with a Sally Award for social impact. In December, Mississippi Creative Arts School in St. Paul named their library after her.

Whew! What will 2020 bring? Well, three things for sure: a new book in May ("The Shared Room"), a new book in August ("Somewhere in the Unknown World: A Collective Refugee Memoir") and a new book in October ("The Most Beautiful Thing"). And who knows what more?

By LAURIE HERTZEL / photo by SHEE YANG

LET'S NOT FORGET

Lizzo

Ex-homie of the year

She dominated our year-end coverage in many of the six years she lived in Minneapolis, but the "Truth Hurts" hitmaker is local no more. So we'll leave her to Time and Entertainment Weekly magazines, which named the Billboard chart-topping singer/rapper their entertainer of the year. Still, her success marked a breakthrough for the long-incubating Twin Cities hip-hop scene, which helped define her sound, image, feminism and Prince-like fearlessness. And though she got her start in Houston and lives in L.A. now, we didn't hear the Texans or Chargers getting a shout-out in her songs, like the Vikings did.

Prince

Ghost of the year

Three years after his death, we rediscovered the prolificness of Prince, thanks to albums that unearthed treasures from his legendary Paisley Park vault. "The Originals" featured Prince's versions of songs he penned for the Bangles, the Time, Sheila E., Kenny Rogers and others, while the recent "Super Deluxe" reissue of "1999" included two dozen 1980s nuggets from the Chanhassen safe. Keepsakes from the vault also turned up in "The Beautiful Ones," Prince's mini-memoir with handwritten lyrics, family photos and other ephemera, which went to No. 1 on the New York Times bestseller nonfiction list. And this is just the tip of the Purple iceberg.

Parkway Theater

Reborn venue

Last year's structural renovations were modest compared with the programmatic overhaul at this neighborhood movie theater, located at 48th and Chicago in south Minneapolis. They still show movies — mainly retro-'70s and '80s fare for Gen-Xers and their kids; the former can partake of draft cocktails and microbrews while the latter learn how to play pinball and Centipede pre show. But there's so much more. Northfield music fixture Jessica Paxton helps book an eclectic mix of singer/songwriters and genre-bending musicians alongside sporadic comedy, dance, podcast and author events, and whatever else works. It's working.