Why did Scandinavian immigrants choose Minnesota?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Minnesota's Scandinavian roots are a big part of the state's national identity, from the Vikings football team to the Norwegian bachelor farmers of Lake Wobegon.

That Scandinavian stereotype harks back to an era when thousands of Swedish and Norwegian people traveled across the globe to establish thriving enclaves in the burgeoning frontier of Minnesota. But why Minnesota?

"When I ask anyone just in casual conversation, they all just say, 'Well, because it's cold here too!'" said reader Terri Stough, who moved to Minnesota in 2018. "And that kind of indicates to me that nobody knows the real reason."

Stough was among several readers who wanted to know how these immigrants heard about Minnesota, and what caused them to settle here. They sought answers from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reader-powered reporting project.

"Was it the free land? Was it that the landscape was similar to theirs?" wondered Paul Welvang, whose great-grandfather left Norway for southeastern Minnesota in the 1880s.

The abridged explanation is that America's westward expansion — and the displacement of Native people that accompanied it — reached Minnesota around the same time that Swedes and Norwegians were fleeing bad conditions in their home countries. Aided by free land from the federal government, new immigrants formed settlements and encouraged friends and family back home to join them.

"If it had happened 20 years earlier or 25 years earlier, maybe we would have been all talking about the Scandinavian immigration in Ohio or someplace farther east," said Bruce Karstadt, president of the American Swedish Institute.

To this day, Minnesota has more residents of Norwegian and Swedish ancestry than any other state, according to U.S. Census bureau data analyzed by the state demographer's office.

'A new Scandinavia'

The impetus for people to leave Norway and Sweden in the mid-1800s began with a positive development — falling child mortality rates. The population of those countries boomed, but the farmland supply and job opportunities couldn't keep up. The resulting poor economic conditions and other factors, like religious conflict and industrialization, caused some people to seek an exit, said Bill Convery, research director for the Minnesota Historical Society.

An early wave of Scandinavian immigrants — primarily farming families — came to America before Minnesota was even a territory. Many Swedes headed for Chicago and the surrounding agricultural areas of Illinois, according to the book "They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State's Ethnic Groups." Norwegians often settled in parts of Wisconsin and Illinois.

But these early settlement areas grew increasingly congested, causing some immigrants to look west in the 1850s to the new opportunities available in Minnesota, according to the book. Several treaties taking land from Native people during this period opened up large swaths of the territory to white settlement.

Prominent Swedish author Fredrika Bremer helped establish the area's reputation as a hub for Scandinavians. Bremer journeyed to the Minnesota Territory in 1850 and wrote letters home that were later published into a Swedish book.

"This Minnesota is a glorious country, and just the country for northern emigrants," Bremer wrote. "Just the country for a new Scandinavia."

"The climate, the situation, the character of the scenery agrees with our people better than that of any other of the American states," she added, "and none of them appear to me to have a greater or a more beautiful future before them than Minnesota."

Minnesota's first Swedish enclaves sprang up in 1851 in the Chisago Lakes area, northeast of the Twin Cities, according to "They Chose Minnesota." Norwegians initially settled the areas of southeastern Minnesota in 1852.

'America fever'

Minnesota's population in 1860 was just over 170,000 people, a third of them foreign-born, according to the state demographer's office. A population boom was about to hit the state, driven in part by mass immigration from Norway, Sweden and Germany.

Conditions had worsened in Norway and Sweden by the 1860s, as famine gripped the region and left many residents starving.

"You have all of these young people who don't have the opportunities to take up farmland …And now they're hungry and they've got to go somewhere," Convery said.

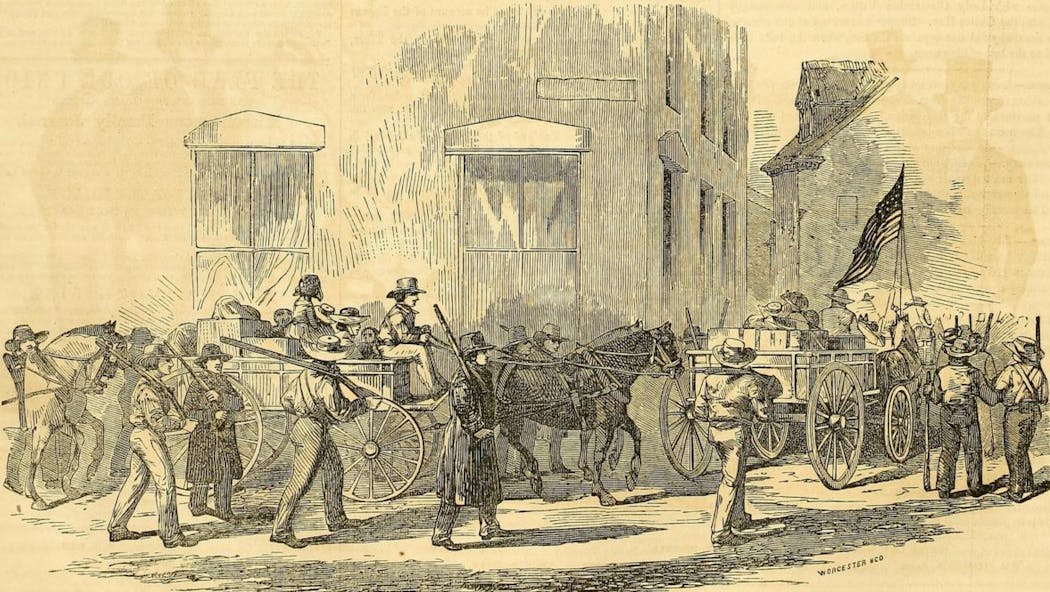

The United States government, meanwhile, forced the Dakota people from the state after the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. That same year, it passed the Homestead Act, offering 160 acres of land for free to settlers who agreed to live on it for five years. Railroads also began connecting all corners of the state to the rest of the country.

Minnesota's immigrants sent influential letters back home that helped fuel "America fever" overseas. Those who made the journey often linked up in Minnesota with people from the same Scandinavian regions, according to "They Chose Minnesota."

Among those letters was one sent by Norwegian immigrant Jens Grønbek, who wrote to his brother-in-law in Norway in 1867 trumpeting, among other things, the free land available through the Homestead Act.

"If you find farming in Norway unrewarding and your earnings at sea are poor, I advise you ... to abandon everything, and — if you can raise $600 — to come to Minnesota," Grønbek wrote, according to the book.

Grønbek told his friend that he should not worry about the voyage, adding this racist assessment: "Neither should you be alarmed about Indians or other trolls in America, for the former are now chased away," Grønbek wrote.

Official efforts

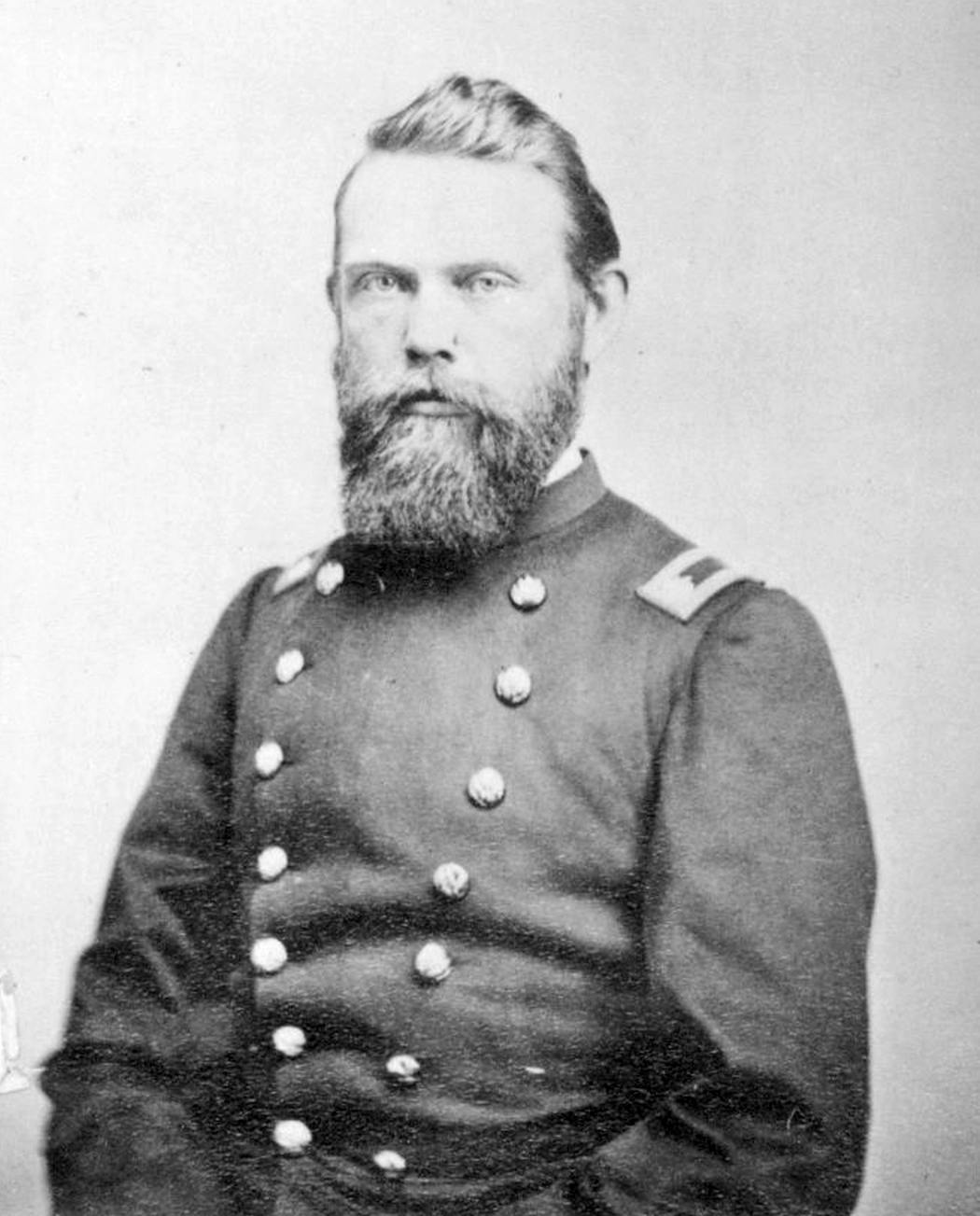

Some of Minnesota's efforts to attract immigrants were more official. The state created a Board of Immigration in 1867 to lure certain immigrant groups, for example, with Swedish immigrant Hans Mattson as its first leader.

The board appointed agents speaking Norwegian, Swedish and German to meet immigrants at New York and Quebec and guide them on their journey to Minnesota, Mattson wrote in his memoirs. It also printed detailed pamphlets like "Minnesota and its Advantages for Immigrants," which were translated in multiple languages and distributed overseas, on ocean liners and in railroad stations.

"On my visits among our western farmers years afterwards I have often seen pamphlets in Swedish and Norwegian with my name as author standing in the little bookshelf side by side with the Bible, the prayer-book, the catechism, and a few other reminiscences from the old country," Mattson wrote.

The new immigrants gradually spread from their initial settlements to other corners of the state, and by the 1880s more began moving into Minneapolis and St. Paul, according to MNopedia, the Historical Society's online encyclopedia. By 1900, about 13 percent of Minnesota's population was born in either Norway or Sweden, according to the state demographer's office.

"Why do Scandinavians come to Minnesota?" Convery said. "Because when Scandinavians were most in need, the greatest opportunity happened to be in Minnesota."

Suppressed German culture

Despite Minnesota's Scandinavian reputation, more people in the state actually report having German heritage.

That stems from a similar mass migration of Germans to Minnesota in the 1800s. Beyond seeking better economic conditions, Convery said many Germans were also spurred to leave their homelands due to war and failed revolutions.

By the time World War I began, German was the most common non-English language spoken in Minnesota schools, according to a 1981 historical society article.

"There were a lot of people thinking that the German culture was the predominant culture in Minnesota," said Dave Bredemus, a retired St. Paul teacher with a passion for German Minnesota history who has given tours on the topic.

But that German culture was suppressed for a number of reasons, Bredemus explained. Many people did not trust Germans as a result of World War I. Germans also organized unions, which were controversial. And drinking is a part of German culture, a practice that was demonized by puritanical groups during Prohibition.

During the war, statues were torn down, streets and buildings were renamed, and a new Minnesota Commission of Public Safety harassed the state's German population while trying to root out unpatriotic sentiments, Bredemus said.

These complexities of immigrant life in the early 20th century were depicted in the 2005 film, "Sweet Land," which focuses on a woman's arrival in rural Minnesota from Norway. The discovery that she is German leaves her shunned in her new community.

"This was history that has been hidden, it's not been told," Bredemus said. "And German culture in America was destroyed."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How did Minnesota become the Gopher State?

Is Minnesota actually more German than Scandinavian?

Where does 'uff da' come from, and why do Minnesotans say it?

What are the top five immigrant groups in Minnesota?

How did early settlers survive their first Minnesota winters?

Why is a casserole called hot dish in Minnesota?