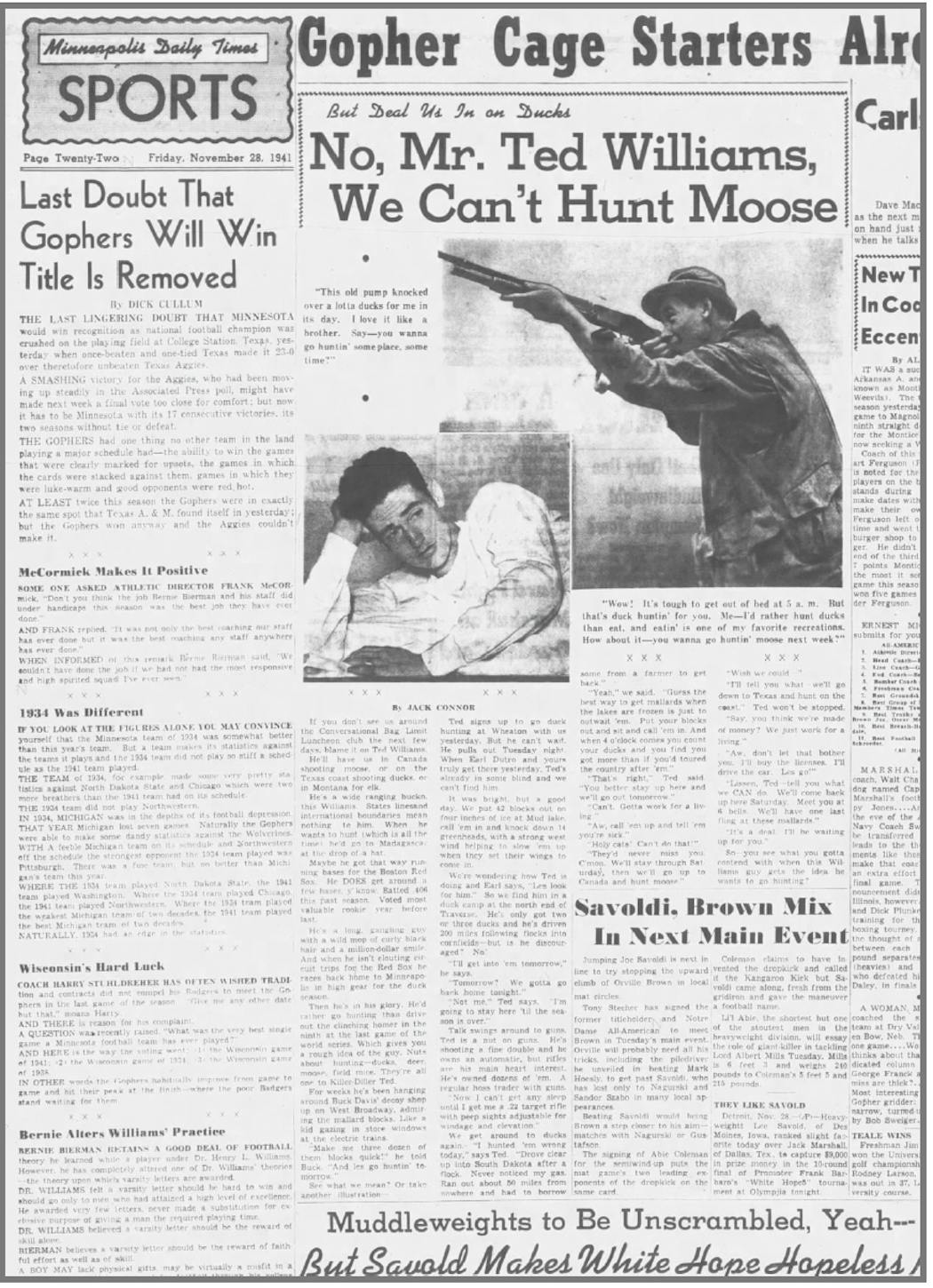

When I first saw the photo sent to me by a reader of Ted Williams, the late great Boston Red Sox slugger, standing alongside nearly 40 drake mallards and a dozen or so pheasants — all apparently felled near the Twin Cities — I wondered what the weather was like in Minnesota 81 years ago this week.

Published Sunday, Nov. 22, 1942, in the old Minneapolis Star, the photo of The Kid, as Williams was nicknamed at age 19 when he first reported to the Red Sox training camp, suggests to anyone who knows anything about ducks that a major weather change in the days just before the photo was taken must have pushed vast flights of mallards over Williams's decoys.

Otherwise, Williams could never have killed that many mallards — not even together with his girlfriend, Doris Soule, who's also in the photo, and especially not in Minnesota, a flyover state where in autumn migratory waterfowl come and go, oftentimes quickly.

And indeed, while the Minneapolis temperature topped out at 60 on Nov. 19, 1942, 16 degrees above average, the next day the high was only 38, and on Nov. 21, it slid to 36, likely accounting for Williams's and Soule's copious harvest.

In the context of today's media-infused sports scene, in which colossal stadiums are weekend sanctuaries and athletes are among the nation's cultural high priests, the colorless image of Williams, his girlfriend and their day's reward recalls a time in Minnesota that was, if not simpler, at least simpler to understand.

This was a period, beginning in 1938, when a gangly kid from California came to Minnesota to play for the Class AA Minneapolis Millers, a Red Sox affiliate, hitting .366 in his first and only year with the outfit, with 46 home runs and 142 RBI.

Williams gained a certain celebrity while in Minnesota and parlayed it into a lifetime of memories. Not so much of walk-off homers in the ninth inning or hero catches at the Nicollet Park warning track, but of walleyes caught on Mille Lacs and enough downed ducks and pheasants to fill a freezer.

"You can say for me the happiest year I ever had was in that great town, Minneapolis,'' Teddy Ballgame, as Williams would become known with the Red Sox, told Halsey Hall in a column published in the Minneapolis Star on Oct. 7, 1946. "Minneapolis and Princeton [the small town just north of the Twin Cities where Soule and her hunting-guide father lived], those I love.''

That same week, while in St. Louis where the Sox were playing the Cardinals in the World Series, Williams wired the Star's outdoors editor, Jack Connor.

"Dear Jack," Williams wrote. "Can't wait to get to Minnesota as soon as Sox take care of Cards. Already got ammo. Will let you know when I arrive."

After leaving the Millers for the Red Sox, Williams's life unfolded like a Shakespearean drama. Three failed marriages punctuated a Hall of Fame career that was interrupted twice by stints as a U.S. Marine Corps fighter pilot. Headlines routinely exalted his game-winning homers while alternately highlighting his feuds with fans and, especially, with the baseball scribes who chronicled his life at the ballpark, and away from it.

Williams nevertheless was happy in his early years as a big leaguer, especially when baseball seasons ended and he returned to Minnesota to hunt.

"He'd rather go hunting than drive out the clinching homer in the ninth in the last game of the World Series,'' Connor wrote in the Minneapolis Daily Times on Nov. 28, 1941. "Which gives you a rough idea about the guy. Nuts about hunting — ducks, deer, moose, field mice. For weeks he's been hanging around Buck Davis' decoy shop up on West Broadway, admiring the mallard blocks like a kid gazing in store windows at the electric trains. 'Make me three dozen of them blocks quick!' he told Buck. 'And let's go huntin' tomorrow!' "

In 1941, Williams won his first of six batting championships, hitting .406 for the season, still the highest in any Red Sox clubhouse and one unmatched in the majors in the years since.

When that season ended, Williams decamped to a $5 room at the King Cole Hotel in Minneapolis, staying there en route to Princeton, where Williams "was said to bat 1,000 with one Doris Soule,'' and would "try to hit four for 10" on ducks, the Minneapolis Star reported Oct. 15, 1941.

Williams and Soule married on May 4, 1944, the same day Williams was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Marines, stationed at Pensacola, Fla.

World War II ended before he saw combat. But during Williams's second call-up, he flew 39 strafing and bombing missions over Korea. Earning the Air Medal with two Gold Stars while piloting a P9F Panther fighter jet, Williams was widely considered an accomplished pilot who once barely escaped death while belly-landing his plane after it was shot up by anti-aircraft fire.

Remarkably, after his second wartime hiatus from baseball, for two years running Williams led the league in hitting, .345 and .356 but lacked the 400 at-bats needed to win the title. In 1960, in his last home game of his last season, he hit his 521st home run.

When Williams stepped away from home plate a final time, he was relieved.

"I'm glad it's over. Before anything else, understand that I am glad it's over," he wrote in "My Turn at Bat," his autobiography with John Underwood. "I wouldn't go back to being 18 or 19 years old knowing what was in store, the sourness and bitterness, knowing how I thought the weight of the damn world was always on my neck, grinding on me. I wouldn't go back to that for anything ... I wanted to be the greatest hitter who ever lived …"

After hanging up his cleats, Williams helped the Red Sox in various capacities and managed the fledgling Washington Senators for three years. But fishing the saltwater flats off Islamorada, Fla., in winter and casting flies to the Miramichi River in New Brunswick, Canada, in summer were his real loves.

In the Florida Keys, Williams was tutored by Jimmy Albright, a guide who along with a small lair of virtuoso fly anglers couldn't care less if the guy in the bow of their skiffs could swing a bat or run down a high fly ball in a deep corner. All that mattered was whether he could spot a bonefish or tarpon in sunlight or shade, double-haul a 10-weight rod, and land a fly in front of a fish's nose, wind or no wind.

"His casts were quick and long, his power was immense," Richard Ben Cramer wrote in the June 1986 issue of Esquire magazine. "He fished with Jimmy week after week, and one afternoon as he stood on the bow, he asked without turning his head: 'Who's the best you ever fished?' Jimmy said a name, Al Mathers. Ted nodded, "Uh-huh," and asked another question, but he vowed to himself: "He don't know it yet, but the best angler he's had is me."

Today, Princeton, Minn., has a population of nearly 5,000, more than double what it was in 1940. Within it are families with the name Soule, but none I could find who were, or are, closely related to Doris Soule or the daughter, Bobby Jo, she had with Williams before they divorced in 1954.

What is known is that this Sunday, Nov. 26, is the last day of the 2023 Minnesota duck season. Known as well is that the two days leading up to the finale are forecast to be among the coldest of this late autumn.

Ducks fly on days like that, when the weather changes, as Williams learned firsthand in Minnesota 81 years ago. And perhaps no waterfowler in history would like one more crack at a mallard passing overhead than the Kid.

Maybe that's why when he died in 2002 at age 83, instead of being buried or cremated, William had his remains cryonically frozen.

Swinging for the fences one last time, he hoped someday to come back to life.

Star Tribune librarian John Wareham contributed to this column.

Anderson: Canoeist found dead in BWCAW was experienced

Anderson: In early June, Minnesota fish are begging to be caught. Won't you help?