FORT MYERS, FLA. – Kirby Puckett liked to get to the Twins' spring training clubhouse early. Before the sun had risen on the morning of March 28, 1996, he drove his rented Cadillac to pick up two young pitchers, Eddie Guardado and Pat Mahomes.

"Every morning he'd pick me up real early and we'd go straight to McDonald's and order about 150 Egg McMuffins," Guardado said earlier this month. "He'd feed everybody in the clubhouse. That morning, I hop in the passenger seat and say, 'What's up?' and he says, 'Bro, I can't see out of my eye. It's blurry. I think I slept on it wrong.' "

The Twins would leave Fort Myers for Colorado that day to play two exhibition games. Puckett would not go with them.

He would say in the clubhouse that he woke up next to his wife, Tonya, that morning, and that he couldn't see her. The Twins would rush Puckett to Baltimore to see a specialist at Johns Hopkins. He would be diagnosed with glaucoma. He would never play in another baseball game.

Three-and-a-half months later, Puckett would announce his retirement, famously saying, "Don't take life for granted, because tomorrow isn't promised to any one of us."

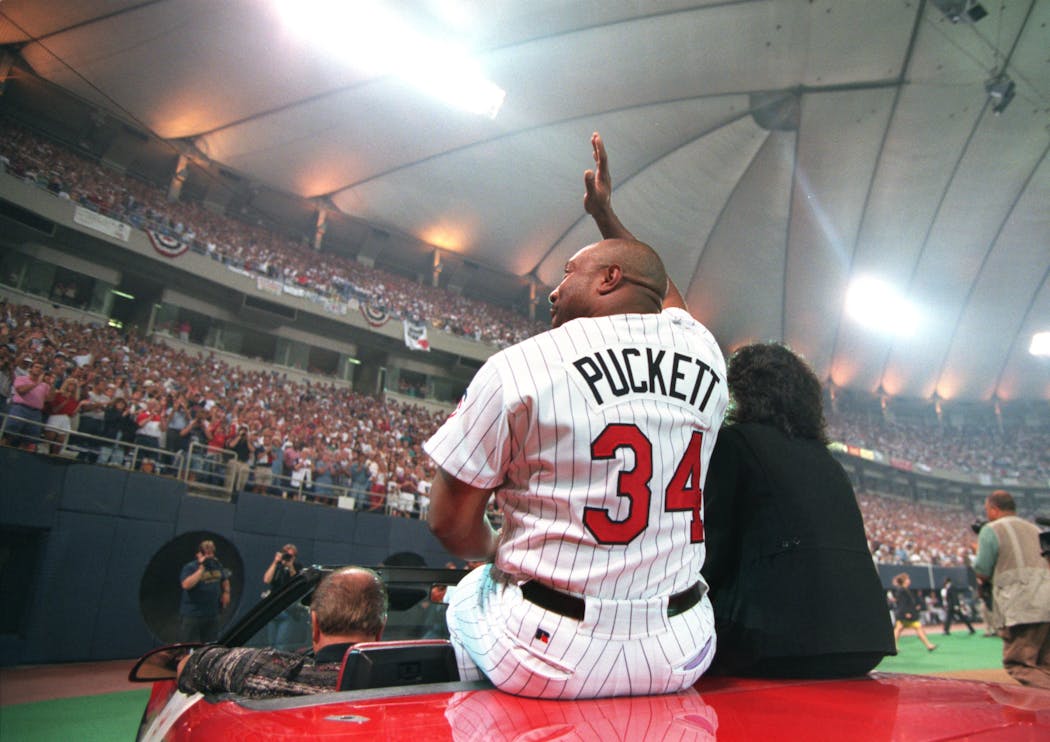

Five years after that speech, Puckett would be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Five years after his induction, Puckett, just 45, would suffer a massive stroke and die.

His buoyant speech at his induction on a hot day in Cooperstown would stand in contrast to his last decade of life, a decade that started, unexpectedly on a hot, cloudy morning in southwest Florida.

"I'll never forget that morning," said Tom Kelly, the former Twins manager. "He walks in and he's screaming, 'I can't see, I can't see!' Everybody thought he was just being Kirby, fooling around and making noise and, lo and behold, that wasn't the case.

"It was devastating. It's still devastating."

'Can you drive?'

Before March 28, the Twins' camp that spring had brimmed with optimism.

With the arrival of free-agent signing Paul Molitor and the return of Rick Aguilera as a prospective ace that spring, the organization was as optimistic as it had been since 1992, the last season in which the Twins had contended.

Puckett felt optimistic, too. For the first time in his career, he had spent the winter working out, and he had looked all spring like the star who had led the Twins to two World Series titles, even getting two hits off the great Greg Maddux and loudly calling Maddux "Picasso" from second base.

That blend of Hall of Fame skill and persistent joyfulness had made Puckett perhaps the most popular athlete in Minnesota history. Having reached 2,000 hits faster than any player since Wee Willie Keeler, Puckett, who had turned 36 on March 14, was primed to spend the second half of the decade chasing 3,000 hits and re-establishing the Twins as winners.

Then he woke up one morning and couldn't see the person lying next to him.

"When he picked me up, he asked me, 'Can you drive?' " Mahomes said. "He said, 'It's like a cloud over my eye.' When we got the ballpark, I remember him going into the training room and telling them the same thing. They immediately said, 'We have a problem here.' "

Stolen away

Puckett's sudden blindness would change Major League Baseball medical testing protocols, and alter the path of a life, a career, a family and a franchise.

Following their World Series championship in 1991, the Twins were celebrated as baseball's model franchise, a team that won because of intelligence and grit and talented everyday players such as Puckett and Kent Hrbek. They contended again in 1992 before faltering down the stretch, then collapsed for the next three seasons.

In 1996, the Twins thought they would contend. Even without Puckett, they would rank ninth of 30 teams in runs scored. Chuck Knoblauch and Molitor would each bat .341. Marty Cordova would be named American League Rookie of the Year after driving in 111 runs. Put Puckett's bat in that lineup, and he may have produced 150 RBI.

Molitor and Puckett had one spring together. After a few weeks in Puckett's presence, Molitor said of the nonstop chatter, "I understood that there would be quality. I didn't realize there would be this much quantity."

"When I was in Toronto, Puck and I did a commercial together at a private location," Molitor said last week. "That was before I really knew him on a personal level. We took a two-hour shoot and turned it into six hours because we were laughing so much.

"Being around Puck that spring was a revelation. Even after he realized he wouldn't be able to play again, he never showed in any overt way the frustration over what was taken away from him. He used that summer as a time to pick other people up.

"We have a tendency to look at it selfishly, at what we all missed when he was gone, but he had to endure going, in one night, from being an elite player in the game to never being able to compete again. That's hard to imagine."

'Changed forever'

After retiring, Puckett became a Twins executive vice president and in 1996 won the Roberto Clemente Award for public service. By refusing to pity himself, Puckett became as inspirational in retirement as he had been in his prime, but that didn't last.

His Hall of Fame induction in August 2001 was one of Puckett's last celebratory moments in public. In 2002, after 16 years of marriage, Tonya alleged during divorce proceedings that Puckett had abused her and threatened her life. He faced a sexual harassment claim from a Twins employee, and a woman accused him of groping her in a Minnesota restaurant. He was found not guilty of that sexual assault charge in 2003.

Reporting by the Star Tribune, Sports Illustrated and others detailed Puckett's behavior and fall from grace. This attention, and his estrangement from the Twins, prompted him to move to Scottsdale, Ariz., with girlfriend Jodi Olson, who would soon become his fiancée.

Puckett paid $1.3 million cash for a house on Shangri La Road. He had the Hall of Fame logo painted on his sport court.

He spent less time in Minnesota but was hardly forgotten. Six days after his death, more than 15,000 fans drove through a blizzard to get to the Metrodome for a memorial service.

Today, Kirby and Tonya's children, Catherine and Kirby Jr., run Phat Cats Cookies and Bars in Minneapolis. One of their bestsellers is a cookie named "The Kirby."

"They call it the thief in the night," Catherine said in an e-mail about glaucoma. "There are no warnings. I was 5 or 6 at the time, Kirby Jr. was 3. We didn't know how serious it was until we were boarding a plane to go home and the Twins told us how serious it was.

"Life changed forever for us."

She said that if Puckett had been getting regular exams, his blindness may have been prevented. She said that's why she, Tonya and Kirby Jr. created the Kirby Puckett Educational Center for eye care and glaucoma awareness in 2008.

"If he had been getting regular checkups, he would have known that his family had a history of glaucoma," Catherine said.

Puckett expected to play into his 40s, and who could have questioned him? He never went on the disabled list before 1996.

Final swings

His final offseason as a ballplayer was bookended by the two most traumatic days of his career. His 1995 season ended on Sept. 28 when Cleveland's Dennis Martinez hit Puckett in the head with a fastball, breaking his jaw.

"That led to speculation that the beanball led to his eye problems, but that wasn't the case," said Dr. John Steubs, then the team medical director and orthopedist and now the team's medical director emeritus. "He was hit in the left side of his face, and the glaucoma was in his right eye."

Steubs and the Twins' medical team tended to Puckett in the team's training room after he arrived that morning.

"We quickly got him to a local ophthalmologist," Steubs said last week. "He could see a little peripherally out of that eye, but was having trouble with his central vision."

Puckett's agent, Ron Shapiro, lived in Baltimore and recommended a specialist at Johns Hopkins. Publicly, the Twins offered little information on Puckett at the time. Privately, they were morose.

"I kept asking, 'In this day and age, isn't this something that can be treated?' " Kelly said. "And they kept saying, 'No.' "

For months after the initial diagnosis, Puckett tried to be hopeful. He underwent at least three procedures on his eye. On May 28, he talked the Twins into letting him take batting practice in Milwaukee. He swung at pitches arriving at 50 or 60 miles per hour but admitted he couldn't attempt to hit big-league pitching until he could "get brightness in my right eye."

That was his last attempt to hit a pitch in a big-league ballpark.

"We all kept saying, 'It's Kirby, he's indestructible, he'll be fine,' " Mahomes said. "We just didn't understand how bad it was."

The news from Florida made the Friday front page of the Star Tribune, topped with a headline that reads hopeful in retrospect: "Vision problems might keep Puckett from Twins' opener."

From the opener, and from the first month, and then the next, and the next, until it was over for Puckett. Twenty-five years ago, Puckett woke up and couldn't see what was in front of him.

"I remember all the young players talking that day, saying, 'Kirby is Superman, he'll be fine,' " teammate LaTroy Hawkins remembered recently. "We had no idea. No idea that his career was over, and what that would mean."

Star Tribune librarian John Wareham contributed to this column.

Souhan: For Lynx star Napheesa Collier, 'Phee' is just fine

Souhan: Will the Wolves trade for Kevin Durant? Should they?

Souhan: If Edwards is a franchise player, he needs to act and play like it

Souhan: Wolves' weak performance in Game 5 invites change, so don't let it shock you