Racial covenants found embedded in Ramsey County property deeds

Jon Neilson learned Tuesday that the bungalow he and his wife, Karli, bought 10 years ago in St. Paul's Como Park neighborhood has a deed saying the owner "can not sell or lease said real estate to a colored person."

"Oh goodness, that's unfortunate," said Neilson, a librarian at Concordia University, when the language of the racial covenant was read to him. Both he and Karli, a teacher at Harding High School, are white.

Arnold Kwong, who is of Chinese descent and also lives in the Como Park neighborhood, has an identical covenant in his deed. Kwong's parents bought the two-story stucco home in 1952 and discovered the racial covenant in the deed in the 1970s when they were preparing their wills.

"You hold this in your hands and say, 'What?' " said Kwong, the owner and executive of a high-tech company. "Your 21st-century sensibilities are offended."

Mapping Prejudice, a local organization that exposes racial covenants in deeds and completed its research on Hennepin County in 2019, released the results of its campaign to document covenants in Ramsey County at a program Wednesday for St. Paul residents at St. Catherine University.

"We really need [the input of] community members who know about their history, what is their experience, whether they lived in a house with racial covenants or couldn't buy a house because of racial covenants," said Mapping Prejudice project director Kirsten Delegard.

The research in Hennepin and Ramsey counties has been conducted by some 6,000 volunteers scouring deeds. The Ramsey County research is far from complete, but so far the group has found about 2,400 property deeds with racial covenants, with nearly 1,200 of them in St. Paul, some dating to 1914.

Delegard said Mapping Prejudice hopes to extend its research to Washington, Anoka and Dakota counties this summer.

Most Ramsey County deeds containing racial covenants appear to have been registered in the 1920s and 1940s. The largest suburban concentrations were found in Roseville, White Bear Lake, Maplewood, Mounds View and the area of Falcon Heights near the State Fair grounds.

State and federal laws now ban housing discrimination and make it illegal for a homeowner or real estate agent to refuse to sell a property to someone on the basis of race or ethnic origin. But many neighborhoods where the covenants were found remain predominantly white.

The Ramsey County Board passed a resolution Tuesday condemning racial covenants and voted to exempt property owners from the $46 recording fee for adding a statement to their deed disavowing a racial covenant.

It also directed county officials to participate in the Just Deeds Coalition — which includes Mapping Prejudice, the Minnesota Association of City Attorneys and the Minneapolis Area Realtors — that's helping to discharge covenants and also helping communities acknowledge a racist past and pursue reconciliation.

"This is such a big deal," said Commissioner Victoria Reinhardt of the board's action. "A lot of people are unaware of the covenants that have been placed."

Mapping Prejudice found about 24,000 Hennepin County property deeds with racial covenants, including more than 8,000 in Minneapolis. The Hennepin County Board passed a resolution in 2020 that allows residents to discharge covenants in their deeds without a filing fee, according to County Auditor/Treasurer Mark Chapin. He said about 600 residents have done so, mostly since 2020.

The earliest racial covenant believed recorded in the Twin Cities was in Minneapolis in 1910. Mapping Prejudice also found large concentrations of racial covenants in Richfield, Edina, St. Louis Park, Golden Valley and Robbinsdale — effectively creating a wall of segregation along Minneapolis' western and southern borders.

Delegard cautioned that people shouldn't assume there was less racism in Ramsey County than Hennepin simply because fewer racial covenants have been found there. Some of the original microfilm of Ramsey County's deeds was unreadable, she said.

More of St. Paul than Minneapolis was platted — when covenants were generally inserted — before 1910, when the covenants first began to appear. Moreover, Ramsey County has 143,275 residential properties, while Hennepin County has about 280,000.

Heather Bestler, Ramsey County's auditor/treasurer, said Mapping Prejudice is asking the county for access to the original deeds, which are easier to read than microfilm. "We are actively working on that," she said.

'Sadly, not surprising'

Racial covenants nationwide, which date to the 1840s in Massachusetts, became more common across the United States in the 1880s, according to Mapping Prejudice. The National Association of Real Estate Boards — now the National Association of Realtors — included in its code of ethics in 1924 a provision "to keep out those who will be detrimental to the house value," which Mapping Prejudice says was code for African Americans.

Redlining, a banking practice that made it impossible to get loans for properties in racially mixed neighborhoods, spread nationwide in the 1930s and blocked Blacks from homeownership. Though the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that covenants were unenforceable, they continued to be applied.

The Minnesota Legislature finally banned new covenants in 1953, and nine years later voted to prohibit housing discrimination in the state based on race, religion or national origin. In 1968 Congress passed the Fair Housing Act, banning housing discrimination nationwide.

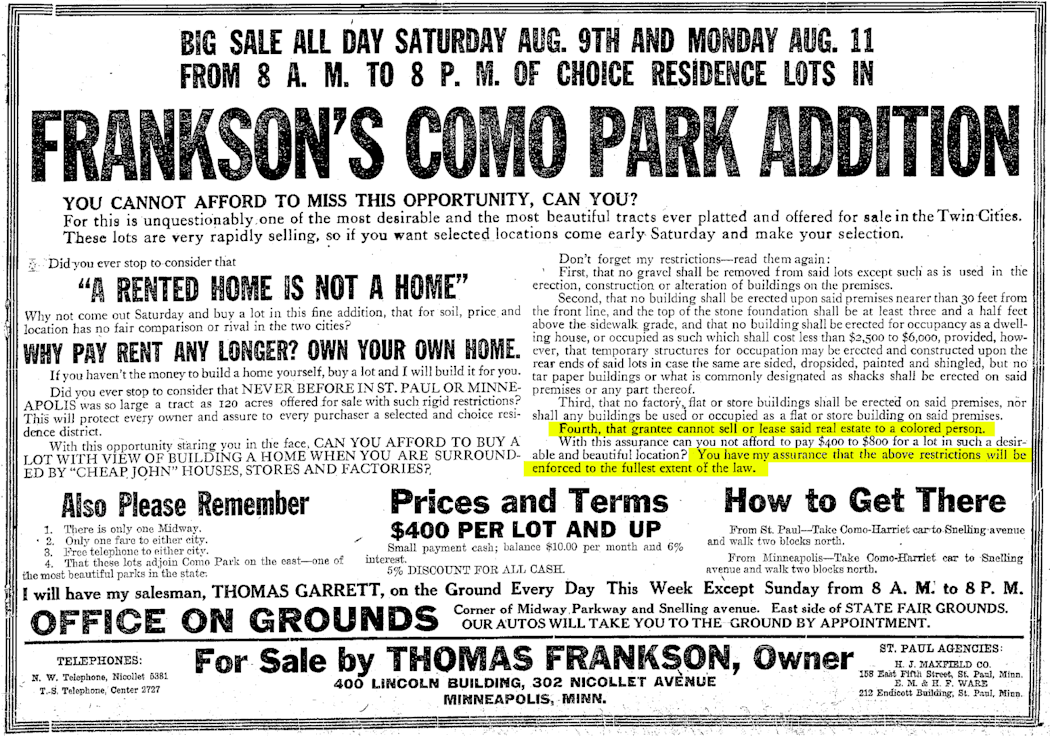

Mapping Prejudice has found newspaper ads placed in 1913 in the St. Paul Daily News and Minneapolis Tribune by lawyer and developer Thomas Frankson that promoted new homes in what would become the Como Park neighborhood. The ads said that the properties could not be sold or leased "to a colored person" and that restrictions would be enforced "to the fullest extent of the law." A similar ad ran in a Swedish language newspaper.

Frankson was twice elected lieutenant governor, serving from 1917 to 1921. A 2010 article about Frankson in Ramsey County History magazine briefly mentions racial covenants but focuses more on his "unorthodox" political history as a Republican often allied with other parties.

Kwong, 66, who lives in the 1300 block of Hamline Avenue, said his house along with others nearby were developed by Frankson. He said neighbors accepted his family, then one of the few Asian families in St. Paul, and that today the neighborhood is more diverse. But he did experience racism; when his name was published in 1978 in the newspaper along with that of his new wife, a white woman, he said he received racist hate mail.

Jon Neilson, 39, said he and his wife were unaware of the covenant on their deed in 2012 when they bought their house in the 1300 block of Arona Street. "It is deeply unfortunate, but sadly, not surprising," he said.

Both Neilson and Kwong said they were inclined to file the paperwork to disavow the covenants. "I would be interested in whatever process the county has established to acknowledge it and rectify it," Neilson said.

Mapping Prejudice's efforts in Ramsey County have energized some neighborhood activists. Laura Oyen said she was leading a Como neighborhood history project with members of the District 10 Community Council in St. Paul.

"People shouldn't be excluded from living in an area because of who they are, their race or their religion or social economic background," Oyen said. "There should be more equity."

To discharge a racial covenant in Ramsey County, go to ramseycounty.us/property and click on "Discharging racial covenants," or call 651-266-2050.