ROCHESTER — Tim Walz can think of nine billion reasons Minnesotans should give him another shot as governor.

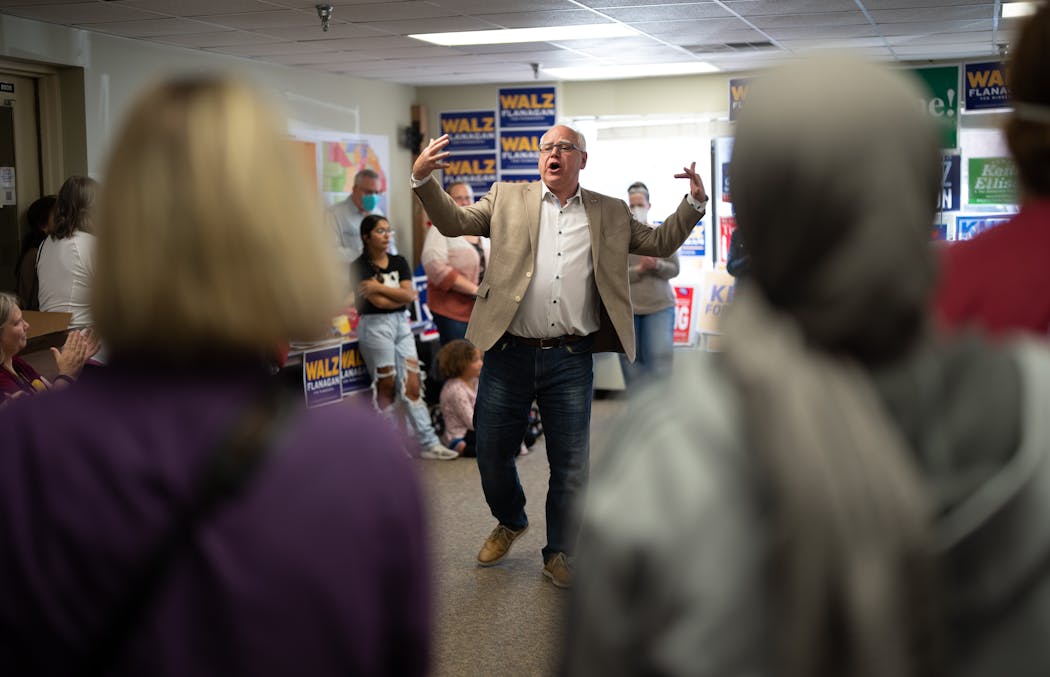

Pacing in the center of a circle of teachers and activists at the local DFL Party headquarters, the Democrat said re-electing him means he'll fight for the state's $9 billion budget surplus left unspent last session to go to schools, child care and direct checks to Minnesotans.

But there are even bigger reasons, he said. Abortion access. Tackling the climate crisis. Defending state elections.

"This election," Walz said, slowing his speech to emphasize his point, "is going to be about a lot of how you just make society work."

Walz is asking for a second act after a tumultuous first term that saw the state grapple with a global pandemic, George Floyd's killing by a police officer and the unprecedented destruction in Minneapolis that followed.

Four years ago, he rode into the governor's office with an ambitious agenda to unite the state's geographic and political divides under "One Minnesota," while investing historic resources into schools and infrastructure and tackling the state's persistent racial inequities. He'd already survived a dozen years in Congress in a conservative southern Minnesota district with his own brand of prairie populism that even opponents say makes him an effective candidate.

Gov. Tim Walz

Age: 58

Education: Chadron State College and Minnesota State University, Mankato

Family: Wife, Gwen, two children, Hope and Gus

What he's reading: "Lincoln Highway," by Amor Towles

Hobbies: Restoring vehicles, teaching his son how to drive, reading scientific articles and taking his dog Scout to the dog park.

"He's a no-nonsense kind of person and down to earth," said Patrick Gannon, a longtime supporter from Rochester who greeted Walz at a recent campaign stop. "It's so refreshing."

But the dueling crises derailed the governor's agenda and threatened his political future. The actions he took to combat the virus created a deep rift over whether he saved lives or went too far. Rioters leveled buildings in Minneapolis and set a police precinct on fire, leaving Walz open to criticism that he didn't act soon enough to stop the destruction.

Republicans are framing the election in existential terms too, arguing that Minnesotans expect basic securities from government that they didn't get from the Walz administration.

Walz leads Republican Scott Jensen in polls and campaign cash, but operatives are blunt about the challenges. Rising crime and inflation have created an uphill climb for his party, and Democrats have never won Minnesota's governorship four terms in a row.

In asking for another four years, Walz is framing himself as the seasoned veteran who led Minnesota through unprecedented times. He now wants another try at the agenda he ran on in the first place. And this election, he says, is about much more.

'The guy you can talk to'

By the time he marched into Camp Wellstone in 2005 to learn how to be a candidate, Walz was a 41-year-old geography teacher and football coach from Mankato with almost no experience. The camp helped candidates like Walz learn how to handle the basics while maintaining their authenticity.

His everyman style is partly credited for his 2006 upset over Republican Rep. Gil Gutknecht, who had represented Minnesota's First Congressional District since 1995.

"He's a progressive but he knows how to change the oil on his own car," said Richard Carlbom, a DFL consultant who worked on Walz's congressional campaigns. "His greatest asset in his time serving in office is he's the guy you can talk to."

As governor, Walz typically shows up to events in a sport coat, jeans and no tie. On a recent tour of a local theater and coffee shop in Rochester, the owner asked him to sign his name on a wall of fame next to action superstar Gerard Butler, another recent visitor.

"Do you think people will confuse the two of us?" Walz laughed, rubbing his hair, which has turned white over his 16 years in politics.

Walz speaks at the breakneck pace of a man fueled by diet Mountain Dew. He moves his arms in fast, rigid motions, like a football coach calling a play in a huddle. Barely pausing for a breath, he rattles off statistics between personal anecdotes and references to things he read in the news.

His candid, circuitous way of talking sometimes gets him in trouble.

Walz recently walked back a suggestion that a judicial ruling be investigated after he was criticized for violating the separation of powers. During an interview at the Minnesota State Fair, in response to a question about the pandemic, Walz said 80% of students missed fewer than 10 days of in-classroom time, despite the fact that he closed classrooms. His staff clarified that he meant 2021, not 2020.

The governor knows he can put his staff on edge during the question-and-answer portion of news conferences.

"When somebody asks a good and insightful question," he said, "I'm sucked into answering it."

A global pandemic

It was the last week of February 2020, and Walz was at the governor's residence catching up on the news when the story popped up. Japan was closing down all of its schools indefinitely.

He recalled turning to his wife, Gwen, sitting beside him. "This is going to be unlike anything we've seen."

Walz had been in the governor's office a little over a year and had early success negotiating a two-year budget deal with a divided Legislature and an agreement to start over with a troubled driver's licensing and registration system. But there was no playbook on how to handle a global pandemic.

A former command sergeant major in the Army National Guard, Walz assembled a team and asked for all the information he could get.

"With this job, you're not hiring someone who knows all this. You might get lucky and get an epidemiologist," Walz said. "In me, you got a high school teacher and artilleryman."

He got daily briefings from various sectors. Then, at 2 p.m., he'd report what he knew back to the public, using charts and graphs to help deliver the latest.

Some days, he'd change Minnesotans' lives. He ordered people to stay in their homes as much as possible for two months. Walz instituted mask mandates and closed businesses and schools to slow the spread of the virus. Plans shifted as the threat of the virus surged and waned.

"There were so many things known now that were unknown then. We were navigating a lot," said Dr. Penny Wheeler, the former CEO of Allina Health, who frequently briefed the governor about hospital bed capacity and personal protective equipment supplies. "He listened and he responded accordingly. That creates a lot of trust."

A strained relationship

By the summer of 2020, Walz's relationship with legislative Republicans was deteriorating. They were critical of COVID deaths in nursing homes and the closing of schools and businesses and felt cut out of the response to the pandemic as a result.

Three months into the pandemic, Floyd was murdered. Rioters caused $500 million in damage to Twin Cities buildings and torched the Third Precinct. The governor called in the National Guard and tapped the State Patrol, but Republicans said the response was too little, too late.

Those relationships remained strained throughout his term, culminating in a blow-up in negotiations this spring over how to spend the multi-billion budget surplus.

That's in part because Walz didn't do the typical relationship building with the Legislature that previous governors did, said Republican House Minority Leader Kurt Daudt. Walz didn't extend lunch or breakfast invites, he said. GOP legislators complained he'd hold events in their districts and not invite them.

"I feel like his only experience before being governor was in Washington, D.C., and that kind of sets the stage for how he thinks about things," said Daudt. "There's a common perception that he doesn't have a lot of respect for the Legislature."

Democrats in control of the House backed Walz on policy issues and his pandemic response. DFL House Speaker Melissa Hortman said the executive branch was poised to respond more quickly than the Legislature, but that came with a burden.

"They had to report those death numbers daily," Hortman said. "The grief of loss of life fell more heavily on the governor and his administration."

A sharper tone

After four years of battles with Republicans, Walz's stump speech has taken on a sharper tone. He frequently jabs the GOP-led Senate — the "reason we can't have nice things" — and employs a burning house analogy to describe the party as a whole.

"What they do is the equivalent of driving down the street and pointing out, 'Oh this house is on fire,' and then continuing on," Walz said. "In some of the cases, yes, it's on fire because you lit it on fire."

To win re-election for Walz, DFL allies are spending millions to define Jensen, his opponent, as extreme on abortion since the fall of Roe v. Wade. Walz's campaign has run ads quoting Jensen saying he'd cut funding for education, describing it as a "black hole." "Those are fighting words," Walz said.

Republicans say Walz is running away from the real issues such as crime and the economy, using the state's low unemployment rate to deflect questions on rampant inflation. They point to rising crime and say police are quitting and demoralized by the riots and Democratic rhetoric on law enforcement.

They've made "Walz Failed" their rebuttal to "One Minnesota," putting the words on a stick and an airplane banner that circled over the State Fair.

"People are concerned about the real issues that are created by bad policy choices by the people that are governing them," said Minnesota GOP Chair David Hann. "They have an opportunity to correct that. That dynamic has not changed."

Walz knows some Minnesotans disagree with his response to both the pandemic and the riots and will vote accordingly.

"When you're the incumbent, it's always a referendum on you, to a certain degree," he said. "The question is what comes after that."

Walz's record 'incomplete'

The governor crouched low to shake the hand of a constituent too young to vote for him.

"Let me see those shoes," he instructed a Zanewood elementary student in Brooklyn Park, who tilted his foot to show Walz the pair he wore for the first day of school.

Even this year's back-to-school ritual came with a dose of reality. In recent weeks, the pandemic's toll on classrooms had come into focus. Test scores were down, student mental health concerns were up. Pondering his own record on schools, Walz paused for a moment and assigned himself a grade: "Incomplete."

When he talks about the next four years, his agenda is long on things he didn't get to in his first term. He wants to enact paid family medical leave and do more to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Classrooms got a boost of funding in his first term, but he says more is needed.

He's proud that he issued zero vetoes, and he hasn't wavered from his idea of "One Minnesota," though he acknowledges the events of the last four years will make it harder to achieve.

Still, he wants another shot.

"Now I'm the veteran who had more thrown at him than ever before," Walz said. "We've really learned a lot; now we can use it."

A profile of GOP governor candidate Scott Jensen was published Oct. 2.