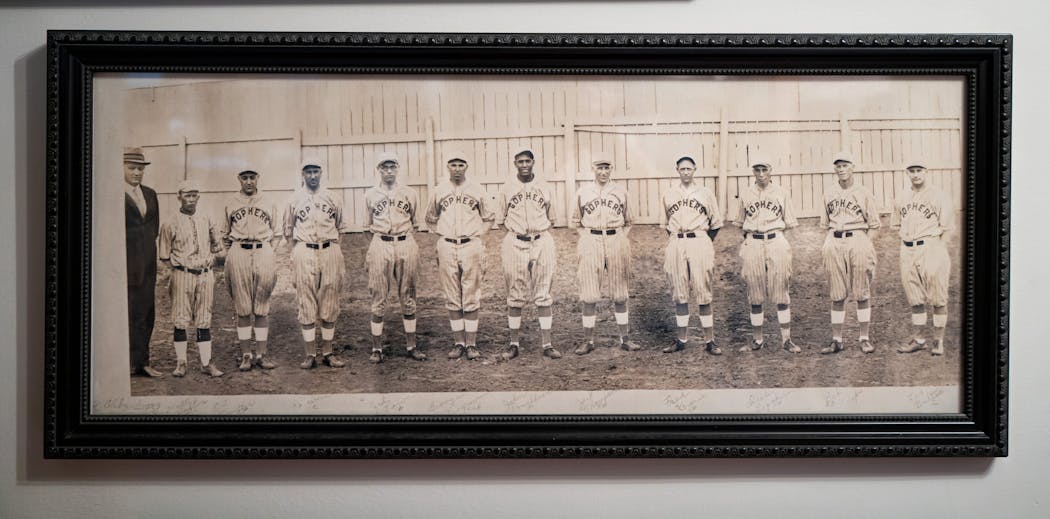

The legacy of one of the great baseball pitchers of the 20th century lives in a basement in New Brighton. It's in the thousands of papers stored in six sturdy wooden crates in the corner of the room, the framed prints of old newspaper articles touting him as "the greatest colored pitcher of today" and photos of early 1900s barnstorming teams, where he's often the only Black man in the picture.

His name was John Donaldson, and he died in 1970 at age 79, buried then in an unmarked grave. But he lives on because of the work of Minnesotan Pete Gorton.

Donaldson's résumé is impressive. He was the first Black scout in Major League Baseball history when the Chicago White Sox hired him in 1949. He was a founding member of the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro National League in 1920.

But Black baseball has a long history that predates the Negro Leagues, and so does Donaldson.

In his 30-year playing career, Donaldson had 422 wins, 5,177 strikeouts, 14 no-hitters and two perfect games in 713 pitching appearances. He played in 744 cities in the U.S. and Canada, including 130 towns in Minnesota. At least those are the numbers Gorton has verified so far in his 21 years of researching Donaldson's career.

Despite his stunning stats, Donaldson isn't widely known. Gorton is trying to change that.

Gorton's mission sounds simple: compile Donaldson's statistics from his decades of barnstorming baseball across the Upper Midwest. But that means scouring newspaper archives for records of Donaldson's games.

Gorton first heard Donaldson's name in 2000, when he was asked to write up a brief biography of Donaldson for a chronology of Black baseball in Minnesota. That short piece led to a decadeslong obsession.

"It's like a bee sting," Gorton said. "As soon as it's happened to you once, you never forget it."

Tremendous obstacles

Gorton believes Donaldson's on-field wonder is more astonishing given what he dealt with off the field.

"He's compared to Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Lefty Grove, legends and icons," Gorton said. "Walter Johnson never slept on the ground. John Donaldson did."

Historian Frank White, author of "They Played for the Love of the Game: Untold Stories of Black Baseball in Minnesota," said that when looking at Black baseball in history, people often stop at the Negro Leagues, overlooking the challenges of playing traveling baseball during segregation. Because Black players couldn't play for major league teams or their affiliates, they played for barnstorming teams, traveling via train and playing in various towns to make money. As they traveled, they often struggled to find hotels, restaurants and gas stations that would serve them.

As evidenced by newspaper articles and ads Gorton has unearthed, Donaldson was well-known in his playing days, renowned as "the greatest colored pitcher in the world."

Donaldson's fame meant that when he came to town, newspapers wrote about him. That's what allowed Gorton to follow Donaldson's career across hundreds of towns all these decades later. Towns wanted Donaldson at their ballparks, as his pitching appearances drew crowds of thousands where normally there might be a few hundred.

"What opened the door for Jackie Robinson to break the color barrier April 15, 1947, was these barnstorming teams were doing so well," said Minnesota Twins curator Clyde Doepner. "They would challenge players from major league teams to games, and they were finding out just how good they were."

Home plate

Gorton grew up in the small town of Staples, Minn., the kind of town Donaldson would have barnstormed a century ago. In fact, Gorton played his last high school baseball game in nearby Bertha, where Donaldson played and pitched a no-hitter in the 1920s. Donaldson's Midwest ties were a large part of why Gorton decided to research him.

Gorton is a baseball fanatic, and two places in his New Brighton home show it: the basement, where he works, and stores and displays records of Donaldson; and the garage.

Half the garage holds tools, bikes and old furniture. The other half is full of baseball memorabilia, including part of his collection of home plates and 35 baseball bats hanging on the wall. One of them he hand-painted with a picture of Donaldson's face. A framed picture of Donaldson hangs next to a giant U2 poster behind a work table.

Researching Donaldson is essentially Gorton's full-time job. He still does freelance broadcast work, and his wife, Kelly, still works in broadcasting. The couple moved from northeast Minneapolis to New Brighton about a year ago to have more room for their two kids, ages 14 and 12, and their West Highland white terrier, Mookie Wilson. And so the boxes containing the story of John Donaldson moved to the bottom floor of Gorton's house.

"When the mortgage is due, when my kid needs a new backpack or school clothes, the box calls and says 'Close me,' " Gorton said. "I believe we have a conscious choice to put the lid on the box or not. And I'm going to choose not."

'Negro Leagues are Major Leagues'

Sports were not excluded from the conversations that erupted last summer about racial equity in the U.S. Teams and leagues nationwide responded with efforts to acknowledge their histories. Doepner and the Twins installed an exhibit at Target Field featuring art and information about some notable Black players from history, including Donaldson. It joined a set of photos in the stadium's Town Ball Tavern, which were already in place, in highlighting Black baseball.

MLB officially designated the Negro Leagues as major leagues in December 2020. Baseball Reference launched its "Negro Leagues are Major Leagues" initiative to add more detailed Negro League statistics to its database. Baseball's top 10 all-time batting average leaders now include Oscar Charleston, Jud Wilson and Turkey Stearnes, with Charleston's .364 average second only to Ty Cobb's .366.

In December, the National Baseball Hall of Fame will consider 10 candidates from before 1950 for induction. For the first time since 2006, Negro Leagues and pre-Negro Leagues Black baseball players will be eligible.

Perhaps Donaldson will have his day, and his legacy will live on outside of Gorton's basement. But Gorton's work was never just about the Hall; it's about respect. It's why in 2004, Gorton helped get a grave marker for Donaldson's previously unmarked burial site in Illinois.

"I appreciate what the Hall of Fame is, but that doesn't validate the day-to-day existence of who he was," Gorton said. "When they start realizing John Donaldson's a ballplayer and stop calling him a Negro Leaguer and we can remember this great baseball player and human being not as less than, that's when it's over."

Lynx overwhelm pesky Wings in the fourth quarter, improve to 9-0

Twins find fuel in back-to-back homers, defeat Blue Jays

Players to watch in Minnesota's girls flag football state tournament

Twins lose Matthews to injury; Woods Richardson likely to join rotation