Our pilot stood on the roof of the yellow submarine named John, floating beside a Lake Superior islet where cliffs rise straight from the water and end in a shock of pines.

Six passengers from the cruise ship Viking Octantis approached on an inflatable Zodiac motorboat. One by one, we climbed on top of the sub, then down the hatch into a submerged cockpit. I took my assigned seat and gazed out the panoramic windows. Today the waters of this big, cold lake, which are often crystal-clear, glistened with an opaque aquamarine.

The passengers, who had been together for the past six days on a Viking cruise of the Great Lakes, laughed nervously, remembering a casual line from the submarine safety video: "If the pilot becomes unconscious, press the green button." I eyed the green button, just below the controls.

We wouldn't be needing it.

The pilot, Philip, relayed our location to Octantis and filled the diving tanks with water, as the sub slipped below the surface. We gently descended, ever deeper into the turquoise abyss. At some 130 feet, Philip activated the thrusters and navigated to the base of a rock wall. I realized that Pyritic Island far above us was merely the tip of a tall sea stack. We were now at the bottom of it — and I was glimpsing the world's largest freshwater body as very few people have.

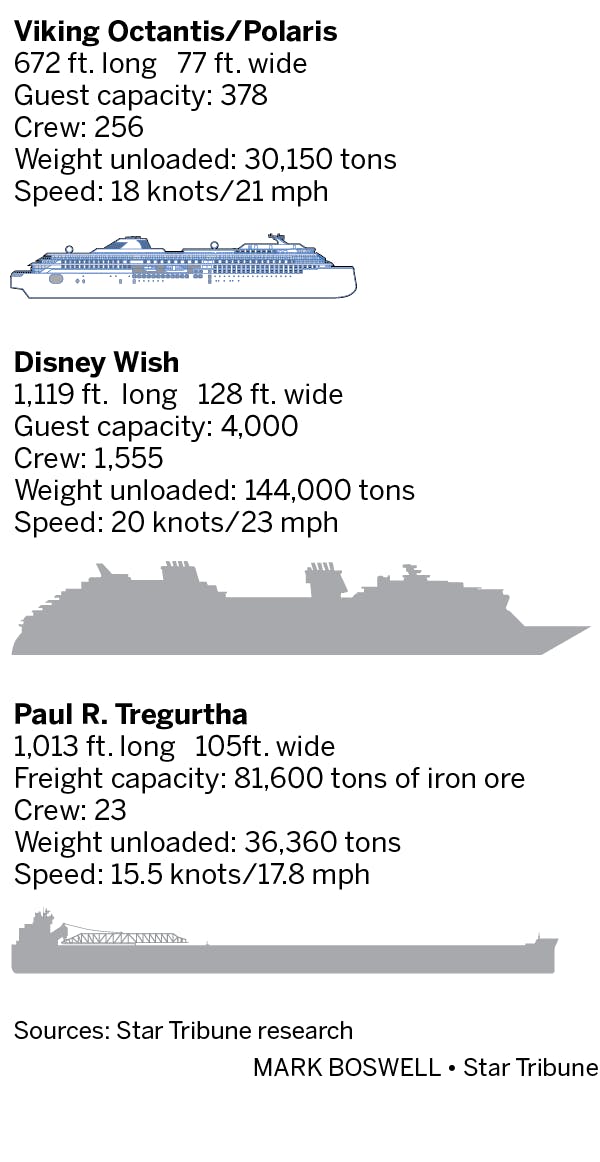

Submarine dives are just one way Viking is trying to thread the needle for leisure cruising and scientific exploration in Octantis' maiden season. When the Norwegian-flagged cruise line announced in 2020 plans for two new expedition-class ships, purposely built for Antarctica and the Great Lakes, it promised to be a sea change for tourism on our inland seas. The gleaming white, $225 million Octantis debuted in harbors from Toronto to Duluth this spring, on a string of lake-spanning itineraries. Its sister ship Polaris will follow in its wake.

In late July, I found my way onto Octantis' seven-day, Canada-centric "Great Lakes Explorer" cruise from Milwaukee to Thunder Bay, Ontario. I wanted to find out if the Viking experience lived up to the hype — and the luxury-caliber pricing. I went into it as something of a cruise skeptic. But I love the Great Lakes — so I had to be on this cruise.

New vistas

On a Saturday morning my cruise companion and I flew to Milwaukee and shuttled to the docked 665-foot Octantis, where a mostly retirement-age demographic lined up for vaccination and customs checks. Upon embarking on the 378-passenger ship, it was hard not to be dazzled.

A fifth-deck restaurant with sweeping views and an endless supply of chef-driven international food. A Nordic spa. A performance and assembly space backed by a two-story window. Spacious communal areas and hidden nooks, decorated with hundreds of — get this — books, immaculately curated around polar and discovery themes. How would they not slide off their shelves?

Viking's head of science and sustainability, Damon Stanwell-Smith, led a tour of "The Hangar" in the bowels of the vessel. There were two modern submarines, John and Paul (presumably George and Ringo are on the sister ship); two so-called "Special Operations" Boats (SOBs, in crew lingo), built for speed with shock-absorbing seats; and 17 inflatable Zodiac boats for nimble, small-group touring. And there were kayaks. All together, the Hangar is the base for what Viking calls "putting the toys in the water."

But before playing with toys, I decompressed. My companion and I soaked in a trio of outdoor pools on the stern — the lukewarm Tepidarium, the hot Caldarium and the icy Frigidarium — as we watched the Brew City skyline disappear on the horizon like a shrinking island. After a sunset dinner of shellfish bouillabaisse and clam linguine in the Italian restaurant Manfredi's, we had a nightcap in the Explorer's Lounge to the sounds of an indie duo with an enchanting singer-pianist from Kyiv.

I also paid extra for a guided Nordic bathing ritual: repeated cycles in the spa's steam room or sauna followed by shocking visits to the cold-bucket shower or snow-shower room, and ultimately a foot massage.

Our 215-square-foot Scandinavian king suite was as comfortable as any five-star hotel, with one rock-star feature: a floor-to-ceiling retractable window, which allowed us to immerse ourselves in the scenery as it slid by like a Kodak carousel. I left the window wide open on the warm, black night on Lake Michigan, sleeping hard to the crashing of waves and whooshing of the ship. Every morning we would wake to find a surprising new vista through that picture window.

The first morning, we passed under the third-longest suspension bridge in the United States, as we entered Lake Huron for our first port of call, Mackinac Island. Passengers boarded Jedi-orange tender boats to the bicycle-happy Michigan isle where cars are famously banned.

We rode a horse-drawn carriage up to the gargantuan Grand Hotel, still embracing its luxury 1887 roots. After a tour of the quirkily colored suites, we settled in for a lunch of local smoked whitefish in the airy restaurant. I rented a modern cruiser bike and took to the 8-mile paved trail that rims the island, circling back to the lost-in-time downtown. We returned to Octantis on the last tender, definitely wanting more Mackinac.

Toys in the water

On this cruise, each port of call turned out to be more beautiful than the last. Across the Canadian border, that included three days devoted to Huron's 120-mile Georgian Bay, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve with little development beyond the port of Parry Sound, Ontario, and the Irish-flavored outpost of Killarney.

Georgian Bay is also home to the Thirty Thousand Islands, the world's largest freshwater archipelago, and the billion-year-old bedrock of the Canadian Shield. Amid that constant stream of scenery, the crew kicked off its "toys in the water" program of subs and SOBs, kayaks and Zodiacs.

Before the cruise, I had wondered if the science angle was a marketing gimmick. But the Viking expedition team walks the talk, with several ongoing research projects onboard — including work on microplastics — and partnerships with Cambridge and Cornell universities and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The multinational roster includes a climatology and oceanography specialist, two ornithologists, a geologist, a population geneticist and several naturalists, all of whom double as guides. All this allows for a deeper cruise experience than, say, sailing to a Caribbean waterpark island.

After passengers watched field scientists release a weather balloon from the ship at dawn, its real-time atmospheric data was projected at Expedition Central, which functions like a fancy version of the flight tracker on an airplane. A whiteboard was filled with lists of "wildlife we have met," including cormorants, sandhill cranes, watersnakes, red bats and otters; one tour group had reportedly encountered a swimming black bear cub. On a too-short but invigorating kayak tour, a large painted turtle darted under my boat.

In addition to being fun, the "toys" play a key role in the science, too. A Special Ops boat might be used to deploy a camera for underwater mapping. The Great Lakes bottoms are still largely a frontier, and the mapping could have a future application in the exploration of shipwrecks. Viking should definitely get on that; submarine dives to some of the Great Lakes' 10,000 shipwrecks would be tourism gold.

Why did this cruise favor Canadian waters? It turns out that the Jones Act of 1920 bars non-U.S. ships with non-American crews from operating special craft, so for now, the toys stay out of the water in Viking's U.S. ports such as Duluth, Mackinac and the Apostle Islands. (Stanwell-Smith sounded hopeful that that could change, but time will tell.)

In Georgian Bay, I rode a Zodiac to the shores of the classic Okeechobee Lodge, a wood-paneled respite that took me back to the Minnesota lake-cabin resorts of childhood. My three-hour hike to an area peak was canceled due to a wet morning, so I hopped on another Zodiac to explore the quartz-inflected walls of misty Baie Fine, one of the longest freshwater fjords in the world.

Our guide Emily Cunningham, a young marine biologist from England, dropped a cone-shaped plankton net in the fjord and dragged it behind the boat for five minutes, with guests assisting as she shared a story about one of the Zodiacs being punctured by an Antarctic leopard seal. In Expedition Central the next day, we looked at the samples under a microscope, with Emily pointing out phytoplankton, zooplankton and other denizens of the bottom of the food chain.

Such experiments and talks are commonplace during the cruise, so curious passengers can get their science on as much — or as little — as they want. "We don't undertake anything just for the optics. Nothing we do is for show and tell," Stanwell-Smith told me. "And that goes to sustainability, as well."

Superior day

Departing Georgian Bay, we entered a summer storm, and I was thrown off-guard by the sole night of relatively rough sailing. By dawn, though, the books were still on the shelves, and Octantis was calmly coasting through the international tangle of islands between Huron and Superior.

At Sault Ste. Marie on the Michigan side, passengers gathered on the bow to watch Octantis slowly advance into one of the Soo Locks. Lake Superior waters flowed into the lock, raising the vessel about 23 feet. The gates opened and on Day 6, we were finally sailing the Big Lake. Sunset afforded a rare view of Michipicoten, the second-largest island in Superior, looking like a jagged lost world.

The next day we woke up beside the Sleeping Giant. The itinerary's only Lake Superior port of call is centered around Silver Islet, Ontario, a historic mining community near where a pure vein of silver was discovered in 1868. It sits on the end of a 32-mile peninsula along with Sleeping Giant Provincial Park, where towering basalt cliffs are said to be the Ojibwe spirit Nanabijou, turned to stone when white men found the silver. The mining village is now a semi-isolated enclave where the rustic lakefront cottages are called "camps," the fifth-generation residents all know each other and a historic gravesite is overgrown with pines.

After a morning in the village, I took the submarine dive at Pyritic Island, whose name curiously invokes fool's gold. Later I zipped on a snug drysuit and joined the last kayak tour of the cruise. Conditions were perfect, so guide Elsa Ross from Montreal led us out to conquer the necklace-shaped Shangoina Island. We took in a riot of colors, from emerald waters to fallen stones covered in golden lichens known as "fairy puke." Lines of quartz were visible in the sea cliffs, which Elsa noted is where prospectors would look to find the silver.

We crossed to the actual Silver Islet, now just a pile of smooth eroded stones, debris from the mining process over a century ago. Circling the islet, we felt vertigo as we floated over a pair of spooky, gaping rectangular holes leading to the deep. We realized that we were perhaps the first people from Octantis to find the 1,200-foot, 19th-century mine shaft. It was a fitting end to a cruise about discovery. That evening, Octantis sailed the short remaining distance to Thunder Bay.

Throughout the cruise I met many energetic older people — and some middle-aged ones — who were thrilled to be kayaking, hiking or diving, but a few guests seemed blissfully unaware of (or uninterested in) the expeditions. I wondered if there was a slight disconnect between Viking's Great Lakes adventures and the well-heeled "bucket list" cruising cohort. But Octantis' sailings have sold quickly just as they are. And a lower-cost, family approach would be a completely different kind of cruise than what Viking has forged.

All I know is, the Octantis plied these lakes for seven days at a leisurely 18 knots — and it still went by too fast for me.

About Viking's Expedition ships

The $225 million, state-of-the-art Viking Octantis debuted in Antarctica in January, and then launched a new era of high-end leisure cruising in the Great Lakes this summer. Its twin sister ship, Polaris, is nearing completion in Norway, with Minnesotan explorer Ann Bancroft as its ceremonial godmother. The liners were "purpose-built," Viking says, for immersive explorations in harsh, remote destinations. Expedition equipment in the Hangar includes two submarines, two muscular "Special Operations" boats, 17 rigid inflatable Zodiacs, and kayaks. At the end of Northern Hemisphere summers, Octantis and Polaris will ship out to Antarctica.

Staterooms

Most guest rooms are 215-square-foot Nordic Balcony cabins, with king beds, en suite bathrooms, French balconies with retractable floor-to-ceiling windows, and an overall Scandinavian design. (Mercifully, there are no windowless staterooms.) These rooms are priced starting at the cruise's lowest all-inclusive base fares, which typically sell out as much as a year in advance. More elite (and expensive) choices range from the 270-square-foot Nordic Penthouse Suite to four 580-square-foot Explorer Suites and a single 1,225-square-foot Owners Suite.

COVID-19

The CDC stopped monitoring coronavirus spread on cruise ships in July, leaving regulation to the cruise lines. For a Viking cruise on July 30-Aug. 6, passengers were required to be fully vaccinated and submit a negative test. Masking was "strongly encouraged" onboard. Distancing was generally easy, but occasional crowding is inevitable.

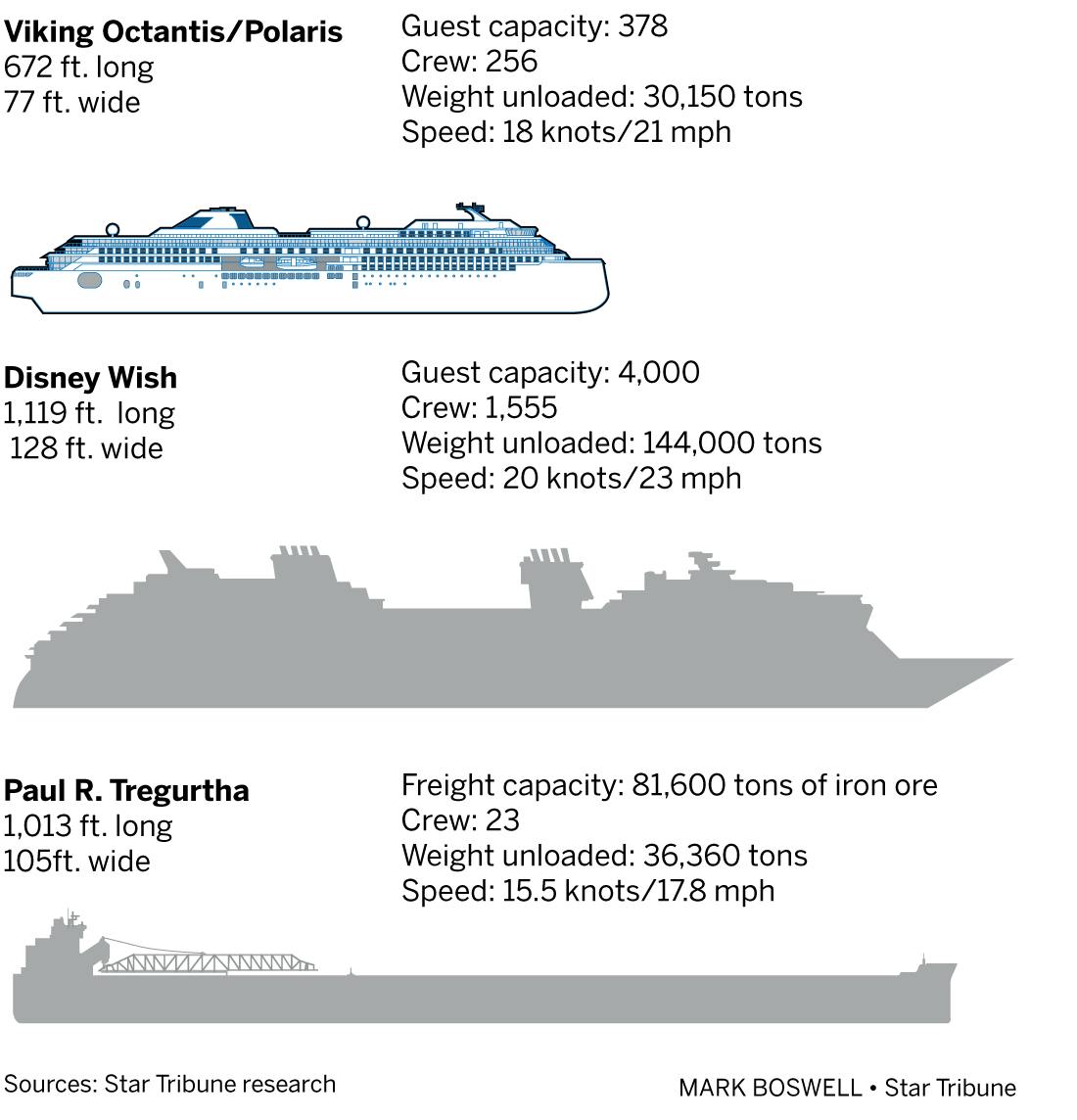

Comparing ships

Viking's Great Lake cruises

Viking Mississippi

The other side of Viking's invasion of the Midwest: cruises on the Great River. The new 386-guest Viking Mississippi features river-view staterooms and an infinity plunge pool, but no submarines. Itineraries include an eight-day St. Louis-to-St. Paul journey from $4,499 and a 15-day St. Paul-to-New Orleans voyage from $12,999.