When you flush a toilet in the Twin Cities, where does everything go?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

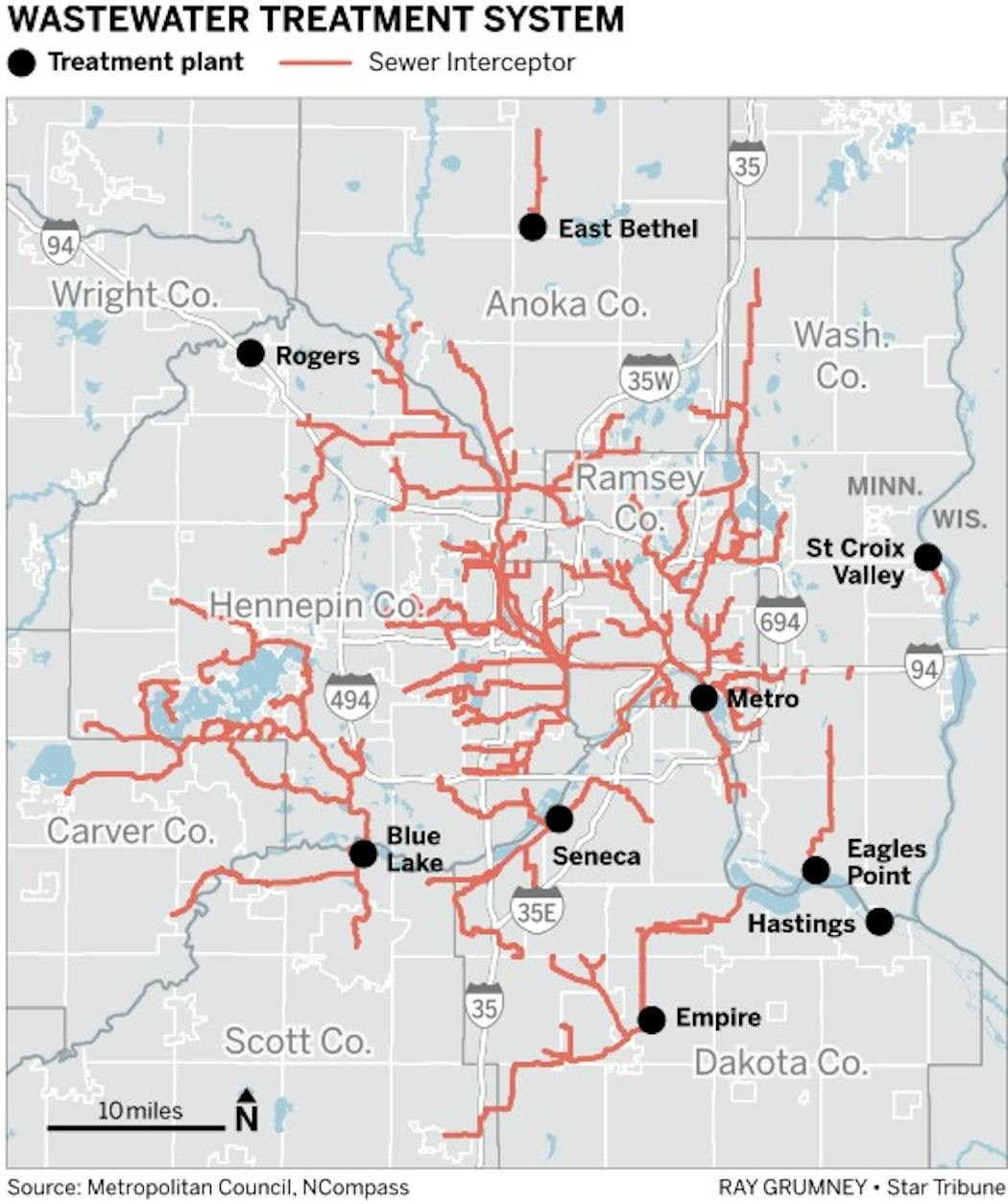

Most maps of the Twin Cities prominently feature the highways and bridges that connect our region. But few show another grid that is even more crucial to daily life in our modern metropolis.

It just transports poop, not people.

Flush a toilet or take a shower and that water begins a journey — sometimes lasting more than a day — on a network of pipes to be purified at one of nine regional treatment plants. That enormous wastewater system operated by the Metropolitan Council rarely garners much public attention, largely because it works efficiently with few major disruptions.

David Piper wanted to know what happens to all that sewage we produce, specifically in Hennepin County. He asked the Star Tribune about it as part of Curious Minnesota, our community reporting project based on smart questions from inquisitive readers.

"What happens when you take a shower, or go to the bathroom. Where does it all go?" Piper asked. "Does it end up in the Mississippi or some other space? And then what kind of condition is it in when it enters the next body of water?"

The answer depends on where you live. But for about 70 percent of the metro area, the stuff people flush flows to the Met Council's massive Metropolitan plant, which is tucked in an industrial corner of St. Paul alongside Pig's Eye Lake.

It is one of the largest wastewater plants in the country by capacity, purifying water from both the urban core and suburbs as far away as Forest Lake and Anoka. The plant churns through about 170 million gallons of water per day, fed by large underground collector pipes, including one buried 200 feet below Interstate 94.

The first stop for all that water is to pass through a series of metal grates spaced about a half inch apart, which removes larger debris. That includes a lot of hygiene products and rags — as well as the occasional tire and bowling ball. That material is later landfilled.

"There's a fair amount of food packaging, potato chip bags, fast food containers," said Met Council spokesman Tim O'Donnell. "However people somehow get that down the drain, it ends up at the treatment plant."

The water then heads to the first step of purification, which uses gravity to remove waste. In holding tanks, heavier solid material is allowed to gradually settle to the bottom, while oils and greases rise to the top. These are known as "sludge" and "scum," respectively, in wastewater terms.

"Gravity is cheap and it works," said George Sprouse, who oversees the Met Council engineers and scientists who work on the purification operation.

That wet sludge goes through several stages of drying before it can be incinerated, including a spin on a giant centrifuge. By the time it reaches the fire, it resembles damp garden soil. The plant's three incinerators — a fourth is being planned — convert all that solid material into ash that measures about 5 percent of its original volume.

Both the ash and the scum are landfilled.

The second stage of water purification is more complex. It relies on colonies of microorganisms feasting away at pathogens, nutrients and organic material in the water, similar to what occurs naturally in rivers and streams.

Met Council staff help grow those colonies by pumping oxygen into special tanks and tweaking the environment to ensure the right type of bugs are there — like those that consume phosphorus, for example.

"We have some of the best biological phosphorus removal that you will ever see," Sprouse said. "It's a biological process that doesn't require any chemicals."

The microorganisms are constantly regenerating.

"The bugs are growing fast enough that they spend about 10 days in the process before they're wasted," Sprouse said. The wasted bugs are incinerated.

About 12 hours after it arrived, the water is now ready to flow into the Mississippi River. During the summer months, when people may be swimming, it is further disinfected with bleach and a bleach neutralizing chemical.

It is cleaner than the river it is entering, but the council says it is not safe enough to drink. Minneapolis and St. Paul residents drink water pulled from the Mississippi River, but only after purification at special drinking water treatment plants.

The Metro plant, which opened in 1938, has "Platinum 7" status with the National Association of Clean Water Agencies for achieving seven consecutive years of full compliance with its environmental permits. It expects to reach "Platinum 8" this summer.

---

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Does Minnesota really have the worst winters in the country?

What are the roots of the Minneapolis vs. St. Paul rivalry?

When did wild bison disappear from Minnesota?

Why do electric-vehicle owners pay a surcharge in Minnesota?

Is Minnesota actually more German than Scandinavian?

Why are felons stripped of voting rights, and what other rights do they lose?

How did Minnesota's early settlers make it through the dark, cold winters?

Why do we have water towers and what do they do?