Why did Minneapolis tear down its biggest train station?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Via Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher

Studying abroad in Europe many years ago, Marcus Nielson took note of the central role train stations played in city design there. When he returned to Minneapolis, he realized something was missing.

"I always kind of wondered why Minneapolis didn't keep a lot of their train infrastructure," Nielson said.

He was aware of the Milwaukee Road Depot, a train station that has been restored downtown, but wanted to know why the city demolished its larger station, the Great Northern Depot. Nielson sought answers from Curious Minnesota, a Star Tribune community reporting project fueled by great reader questions.

Located beside the Mississippi River on Hennepin Avenue, the Great Northern Depot was a de facto welcome mat for the city for many years. When it opened in 1914, the bustling station serviced more than 100 trains a day, traveling everywhere from St. Cloud to Vancouver.

Harry Truman, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dean Martin, Jimmy Durante — the Great Northern was host to all manner of celebrities and everyday travelers, many arriving on trains that passed over the Stone Arch Bridge with a view of St. Anthony Falls. It was the site of jubilant homecomings and the starting point for many parades.

But when the wrecking ball came for the Great Northern Depot in 1978, no one stepped forward to save it. That's in stark contrast to the Milwaukee Road Depot, which was put on the National Register of Historic Places the same year.

"If the question arose today, you would find more voices calling for preserving such an iconic anchor of the history of Minneapolis," said Andrew Selden, president of the Minnesota Association of Railroad Passengers.

Architecture, location and size are among the reasons the Great Northern was erased from the Minneapolis streetscape. But pieces of it live on; some of its mighty granite columns have recently returned to the Minneapolis riverfront after 40 years in the exurbs.

'The humming dynamo'

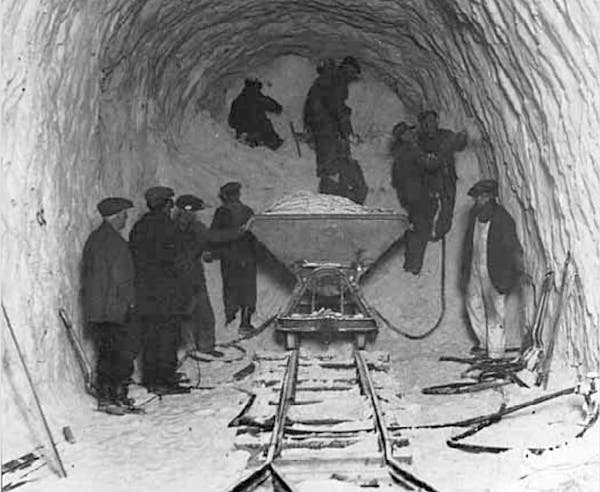

The Great Northern Depot was built to replace James J. Hill's 1885 Union Depot on the south side of Hennepin Avenue, which had become too small for the city's growing train traffic. An ad for the new Great Northern station trumpeted it as "the humming dynamo of Minneapolis' commerce with the outside world."

The stately building's colonnade and arched entryways made it a recognizable downtown landmark, visible from shops several blocks away on Nicollet Avenue.

Trains came and went from platforms beneath the station, some of which are now popular riverside recreational trails and parkways. Visitors leaving the station would walk into a Minneapolis largely unfamiliar to modern eyes, with rows of early downtown buildings, clanging streetcars, the Gateway Park and the imposing Nicollet Hotel in the distance.

Train traffic at Great Northern Depot likely peaked in about 1920, with another spike during World War II, according to rail historian Aaron Isaacs. Roughly 50 trains departed per day from Great Northern in 1926, about twice as many as Milwaukee Road depot.

Growing automobile ownership decimated short-distance rail travel in the 1920s, Isaacs said. As paved roads became ubiquitous in the 1920s and 1930s, buses then began competing with trains for passengers. The final blows came in the late 1950s, with the advent of jet air travel and interstate highways.

"That really dropped the bottom out of train travel," Isaacs said.

The end of the line

Railroad companies had to keep operating money-losing passenger rail routes as part of their obligation as "common carriers." That changed in 1971, when the federal government created Amtrak to operate passenger service across the country.

Overnight, trains stopped serving Milwaukee Road Depot and St. Paul's Union Depot. Amtrak continued using the Great Northern Depot for a handful of departures per day, until erecting the smaller Midway station to more efficiently service both Minneapolis and St. Paul.

"You had these enormous train stations that were suddenly way too big — and way too expensive to operate therefore — than what Amtrak needed," Isaacs said. "They needed downsized facilities."

The City Council signed off on the demolition permit for Great Northern Depot in March 1978, after Amtrak moved out. Burlington Northern Railroad said at the time it would cost more than $1,200 a day to heat, maintain and guard the vacant property. "No group or organization has come forward to try to save the building," the Minneapolis Star reported.

Several months later, the Milwaukee Road Depot became a nationally recognized historic place. The building's significant features include its 19th century truss roof train shed, which the National Register application noted was one of only a dozen of its kind in the country.

Great Northern and Milwaukee Road depots were actually designed by the same architect, Charles Frost, but illustrated very different styles.

Architectural Historian Charlene Roise said Milwaukee Road Depot's smaller size and Victorian architecture — including its rare train shed — likely made it a more appealing target for preservationists, including influential figures like Star columnist Barbara Flanagan.

"It's much easier to get people psyched up for a big old brownstone or a nice Victorian style building," Roise said. "And the Milwaukee Road is ... brick, which people can relate to a lot more than a massive Beaux-Arts stone [building] — which the Great Northern was."

The Great Northern Depot and its underlying tracks were also sitting on prime real estate, as the city revved up efforts to redevelop the riverfront.

"[Burlington Northern] had a vested interest in getting rid of their depot so they could just clear out that area for redevelopment," Roise said.

Not everyone was happy to see the building go. St. Cloud resident William T. Morgan wrote to the Star in 1978 that he was surprised to discover bulldozers chewing up one of his favorite landmarks.

"For those of us who grew up in rural Minnesota, arriving in Minneapolis for the first time by train meant seeing the huge painting on the east wall and hearing sounds echoing through the great 'Roman' space of the marbled waiting-room," Morgan wrote.

The site of the Great Northern is now the headquarters of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, which opened in 1997. The Milwaukee Road Depot was converted to a hotel and event space in the early 2000s. St. Paul's Union Depot had a second life as a home for the U.S. Postal Service, before a recent renovation converted it back into a transportation hub.

The columns return

Most of the Great Northern was sold off or hauled to a landfill. But the columns that once lined Hennepin Avenue recently returned to Minneapolis riverfront after decades at a granite manufacturing site in Delano.

Artist Zoran Mosjilov, who also works with remnants of the famed Metropolitan Building, brought them to his makeshift outdoor studio and sculpture garden behind the former Grain Belt brewery. He has already made some into sculptures, using special abrasives and fire to shape the granite.

"I don't know the history of the train station and who came and who left from this place," Mosjilov said during a tour of the site one recent morning. "But the stones are talking to me. And they are telling me who was there."

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

Why was I-94 built through St. Paul's Rondo neighborhood?

Why does Minneapolis keep planting trees under power lines?

Why are vehicle tabs more expensive in Minnesota than in other states?

Minneapolis plows its alleyways. Why doesn't St. Paul?

Why is Minnesota the only mainland state with an abundance of wolves?

Why is Minnesota more liberal than its neighboring states?