The exuberance Joe Hautman feels about recently winning the federal duck stamp contest a record six times is, well, not so palpable.

A relaxed guy, Joe was in his airy Twin Cities home studio the other day. On his easel was a nearly finished painting of a snowy egret, while scattered about the room's perimeter in more-or-less organized fashion were tools of the artist's trade: brushes, paints, books, posters and prints.

Through the room's large windows an autumnal panorama of trees, water and sky revealed itself, while chickadees flitted about a feeder a short distance from the home Joe shares with his wife, Milla.

"We're getting ready to go to North Dakota duck hunting,'' Joe said, "so I'm putting together things for that.''

"We'' in this instance means Joe and his brothers Jim and Bob, the other members of a familial painting trio (hautman.com) that together has won the coveted federal duck stamp competition 15 times, a record that, unless the brothers clone themselves, likely will stand forever.

Three of seven kids who grew up in St. Louis Park down the street from a couple of other siblings who made a name for themselves in the art world — Joel and Ethan Coen — Joe, Jim and Bob Hautman were part of a large family.

Their mother, Elaine, painted professionally, and their father, Tuck, who instilled in his children a love of nature and of waterfowl and waterfowl hunting particularly, also was handy with a brush.

Yet while the artistic successes of Joe, Jim and Bob might have been predicted due to their lineage, their commercial achievements — their designs grace everything from coffee mugs to curtains and bedspreads — were less certain.

"None of us are really any good at self-promoting,'' Joe said. "Normally in the art world you have to be a bit of a salesman. You have to promote yourself with gallery owners to get your artwork shown. Thanks to the duck stamp contest, we didn't have to do that.''

That's because the contest, which is held annually to determine the design of the $25 federal waterfowl stamp hunters are required to purchase to pursue ducks and geese, is such a big deal that winning it guarantees the kind of prominence (and some fortune) that marketing geniuses can only dream of.

This includes shaking hands at the White House with the president; being ballyhooed at the famed Easton Waterfowl Festival on Maryland's Eastern Shore; and celebrated at the J.N. "Ding'' Darling National Wildlife Refuge on Sanibel Island, Fla. (The winner of two Pulitzer Prizes and a renowned conservationist, Darling designed the first federal waterfowl stamp in 1934.)

Joe won his first federal duck stamp competition in 1991 with a painting of a spectacled eider, an astonishingly beautiful yet reclusive ocean duck most hunters never see. Exquisite as his acrylic rendition of the bird was, Joe was unprepared for the whirlwind that followed.

In part this was because, at the time, he was more of a theoretical physicist than a painter.

"In high school I was interested in science, physics particularly, and also in art,'' he said. "But I figured if I was going to do art I'd do it as a hobby. And I'd study physics.''

Joe's career path thus diverged from those of his younger brothers, Jim and Bob, who started painting as kids, and kept painting.

After high school, Joe took a B.S. in physics at the U, then a doctorate at the University of Michigan in theoretical physics, before undertaking post-doc research at the U and at the University of Pennsylvania.

During this time, he married Milla, who also has a doctorate in physics.

"Jim entered the federal contest in 1987 and took third,'' Joe said. "When he did, we thought, 'Hey, we could actually win this thing.' "

Which the first of the brothers did when Jim, at age 25 (the youngest painter ever to win the contest) took home first place in the 1989 competition, followed by Joe's victorious design in 1991.

"When I won, the people at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who arranged my flight to the Easton Waterfowl Festival said, 'Bring some of your artwork to show,' " Joe said. "Well, I didn't have anything to show — just the spectacled eider I had painted."

In 1996, Bob followed with his first of three federal stamp paintings (he had won state wildlife stamp contests beginning as early as 1987), and the brothers alternated victories in the years since, up to and including this fall, when Joe tied Jim with a record six victories with a painting of three tundra swans.

Bob, meanwhile, took third this year with a rendition of a single wigeon (because Jim won last year he couldn't enter).

Through it all, the brothers, together with Minnesota's many other noteworthy wildlife artists — including Francis Lee Jaques, who painted the 1940-41 federal stamp and the state's current living dean of the genre, Dave Maass, who will turn 93 this month and who won the competition twice) — have ridden a commercial roller coaster that has seen waterfowl paintings rise in value, and fall.

"They used to say the contest winner would make $1 million through the sale of the design's prints," Joe said. "For a lot of reasons, perhaps in part because many duck hunters ran out of space on their walls for prints, that's not true anymore."

So it is that Joe, Jim and Bob augment their print deals with sales of originals and with the aforementioned licensing deals.

And physics?

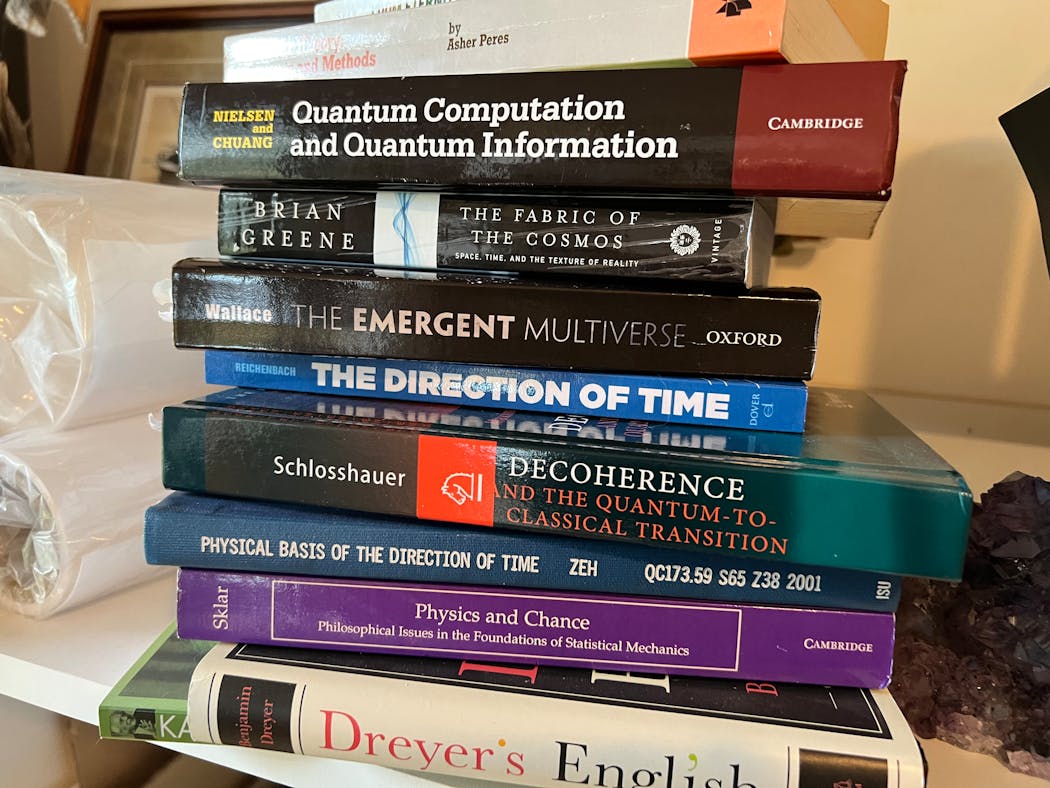

It's never far from Joe's mind, or his bookshelf — witness a tome piled among many others in his studio titled, "The Fabric of the Cosmos: Space, Time, and the Texture of Reality."

"Painting is creating an optical illusion that looks three-dimensional but actually isn't,'' Joe said. "I thought once I could mix colors and paint a duck on water that appears to be rippling. It would be an illusion and I haven't figured out how to do it yet. But that's what painting is, an illusion that looks realistic.''

Anderson: He paddled solo into the BWCAW and didn't come back

Anderson: In early June, Minnesota fish are begging to be caught. Won't you help?