What does it mean when Minnesota courts sentence offenders to 'the workhouse'?

Listen and subscribe to our podcast: Apple Podcasts | Spotify

A landlord who committed perjury. A college football player who raped a fellow student. A former cop who killed a bystander in a high-speed pursuit.

These people who made headlines in recent years did not go to prison. Instead, they served time in the "workhouse."

This word that frequently appears in local news coverage felt outdated to Gary Garnier, who moved to Minnesota from California. Garnier sought more information about these facilities from Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune's reporting project fueled by readers' curiosity.

"Can you tell us what the workhouse is," Garnier asked. "And what work goes on there? Breaking rocks?"

Like prisons, workhouses are secured facilities with guards, cells and solitary confinement. But they are geared toward people serving shorter sentences who are offered more programming as well as the opportunity to leave the facility to attend work.

Minnesota is one of the few states that still refers to these facilities informally as "workhouses," a nickname some would like to see disappear. Populations at these facilities are also dwindling in the aftermath of the pandemic.

What is a workhouse?

Minnesota's four workhouses are officially known as adult corrections facilities or corrections centers. Anoka, Hennepin and Ramsey counties operate workhouses, and a partnership of counties oversees one located 20 miles west of Duluth in Saginaw.

Typically a judge orders someone to the workhouse if their sentence is under a year. If it is more than a year, they go to prison. Workhouse stays are often just a few months.

Unlike prisons, many offenders in the workhouse are allowed to leave during the day to attend work or school. Others work inside the facility itself.

"As a general rule, the workhouse is a form of incarceration that provides punishment and accountability to offenders, but prevents them from losing their job," said Tom Plunkett, a Minneapolis defense attorney.

Plunkett said this benefits the community — in addition to the offender and their family — because keeping a job helps decrease the risks of reoffending.

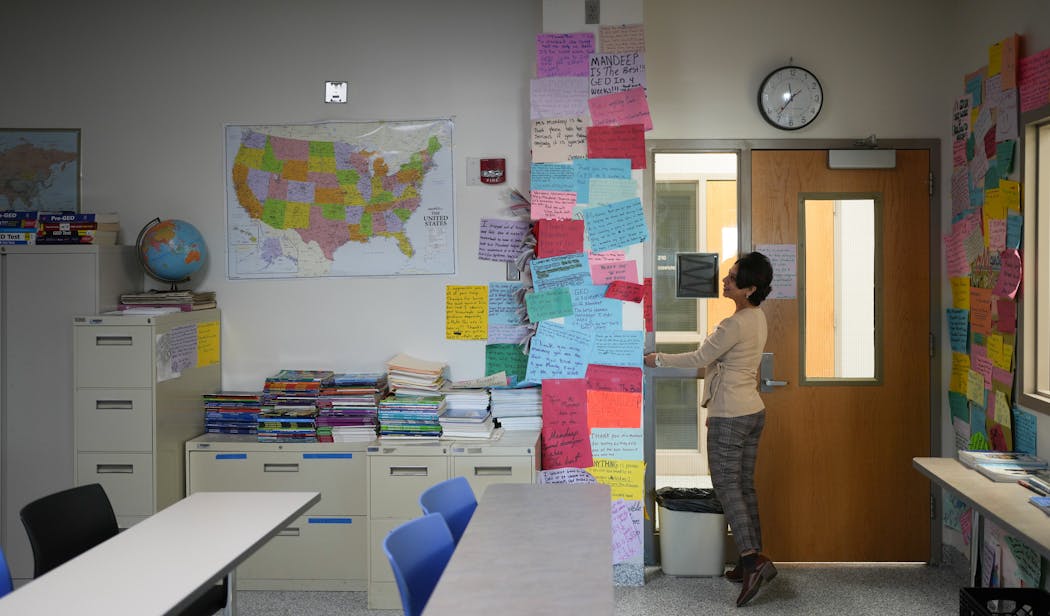

Workhouses today emphasize rehabilitation over punishment, whether that's helping someone earn a GED, receive mental health services, address addiction and anger management or find a job.

Hennepin County Adult Correction Facility Superintendent Coddy Harris said from the moment his staff welcomes a resident (he intentionally does not call them "inmates"), the focus is on their transition back into the community.

"How do we start the process of restoring people and ensuring that people still understand that there's a lot of humane value, regardless of the mistake that they made?" he said.

Offenders who do not qualify for work release might prepare meals in the kitchen, help in the library, or do laundry for Hennepin County's youth detention facility.

All the workhouses are able to help residents obtain state IDs or Social Security cards, study for driving exams or line up postsecondary education and apprenticeships.

The Northeast Regional Corrections Center in Saginaw has a special focus on agriculture. It features a working farm and meat processing facility, the latter of which supplies a new butcher shop. The facility's director, Kathy Lionberger, said they donated 5,000 pounds of excess food to Second Harvest food shelf this year.

"Nothing really good comes out of sitting in a cell," she said. "And it's just so therapeutic for these men. It really helps along with the programming that they're able to get out and work with their hands and learn things."

Saginaw's resident population has returned from a pandemic dip, but the Twin Cities workhouses have about half as many residents as they did in 2019. This is largely due to the rising use of electronic home monitoring (EHM), which tracks offenders using an ankle bracelet equipped with GPS. To limit the spread of COVID-19, the facilities reduced the number of those incarcerated by utilizing EHM.

The origins of workhouses

"The history of workhouse was work," said Paul Schnell, commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Corrections. "It was about the work that people did there to serve their sentence because in many cases they were running farms or industries."

The term dates back centuries to facilities in Britain, where paupers worked in exchange for food and housing. But conditions were often dire. Labor took place on adjacent farms or — like Garnier's question alludes to — involved breaking rocks to produce construction material.

"It had the elderly, the sick, it had able-bodied people, it had children," said Peter Higginbotham, a 20-year expert and author on the topic who lives in northern England. The United Kingdom no longer operates workhouses, and Higginbotham is surprised to still see the term in American newspapers today.

Similar facilities in Minnesota were known in the 19th century as "poor farms."

Residents of Minnesota's "poor farms" sustained the institutions with unpaid labor before the federal government introduced anti-poverty programs, according to research by Macalester College Prof. Jesse McClelland,who recently taught a course on the subject.

Workhouses in Minnesota were often on farms, too, but they were largely penal institutions for incarcerating minor offenses like drunkenness. Minneapolis established its first workhouse in north Minneapolis in 1886.

"I believe it is one of the best means to reform criminals whom we at present punish by confining them in enforced idleness in the county jail," a Minneapolis alderman told the Minneapolis Tribune in 1883.

Minneapolis and St. Paul's workhouses were equipped with dairy barns, brickyards, farms and a cement factory. Minneapolis' moved to Plymouth in 1931, and St. Paul's facility eventually moved to Maplewood. Both came under county control.

An outdated term

Use of the term "workhouse" has declined steadily in American newspapers since peaking in the early 1900s, according to information available on Newspapers.com, a massive database that includes the Star Tribune archives.

Missouri and Minnesota newspapers used it the most in the last decade — though the data may be skewed by which newspapers have been digitized. (Much of the workhouse-related news out of Missouri is from the recent closure and redevelopment of a facility in St. Louis over inhumane conditions.)

Judges and prosecutors in Minnesota still refer to the facilities as "workhouses." But Harris said the word should be phased out.

"It's a loaded term," Harris said. "For me, it has a very negative connotation to it. It was based in this ideology in regards to institutions making profit off of the individuals within."

Harris said superintendents used to live in a house overseeing the fields where incarcerated people worked. While that may explain the namesake, Harris said the idea of those people being a labor force "is not descriptive of anything that we're about or what we stand for."

There is steady interest in workhouse history, Higginbotham said, as more people research genealogy and discover ancestors who were residents of the facilities.

He maintains a list of the facilities that have been converted into museums, which includes the former Redwood County poor farm of Redwood Falls, Minn.

If you'd like to submit a Curious Minnesota question, fill out the form below:

Read more Curious Minnesota stories:

How is the sheriff's office different from the police department?

How safe is it, really, to walk on the iced over lakes in Minnesota?

Did German prisoners of war really work on Minnesota farms during World War II?

Why does Minnesota require new license plates every seven years?

Why do Minnesotans call them 'parking ramps' instead of 'garages'?

How did Stillwater become home to Minnesota's first prison?