One by one, the activists claimed to have evidence of "fraud on a massive scale," repeating discredited claims about election machines championed a year earlier by conspiracists such as My Pillow CEO Mike Lindell.

Although ex-President Donald Trump won nearly two-thirds of the vote in central Minnesota's Crow Wing County in 2020, a group of county residents appeared in droves to urge their government to follow other states in opening up the previous election's ballots in search of malfeasance.

"My heart is telling me that there is something drastically wrong with this election," said Rick Felt, an Army veteran living in the county. "And I urge all of you to follow your heart."

Felt joined a chorus that, starting in October, mounted a vocal months-long campaign that led to a vote last week by Crow Wing County's governing body to formally ask for a new audit of the 2020 election.

They ignored the results of the already completed post-election review that found no widespread fraud in their county — or the annual pre-election equipment security tests done in public view. Instead, many in the group pointed to long-debunked conspiracy theories that still persist among millions of Americans who refuse to accept the results of last year's presidential election.

That they persuaded four of their county's five commissioners to request a new audit more than a year later now has state and local officials worried that such efforts could become a sign of things to come elsewhere even with preparations for this year's next statewide election already underway.

"Unfortunately this is another example, I fear, of disinformation taking root," said Secretary of State Steve Simon. "A generalized feeling or vibe or hunch — and it's probably being stirred up and whipped up by those with a political or financial interest in corroding democracy."

Election results already verified

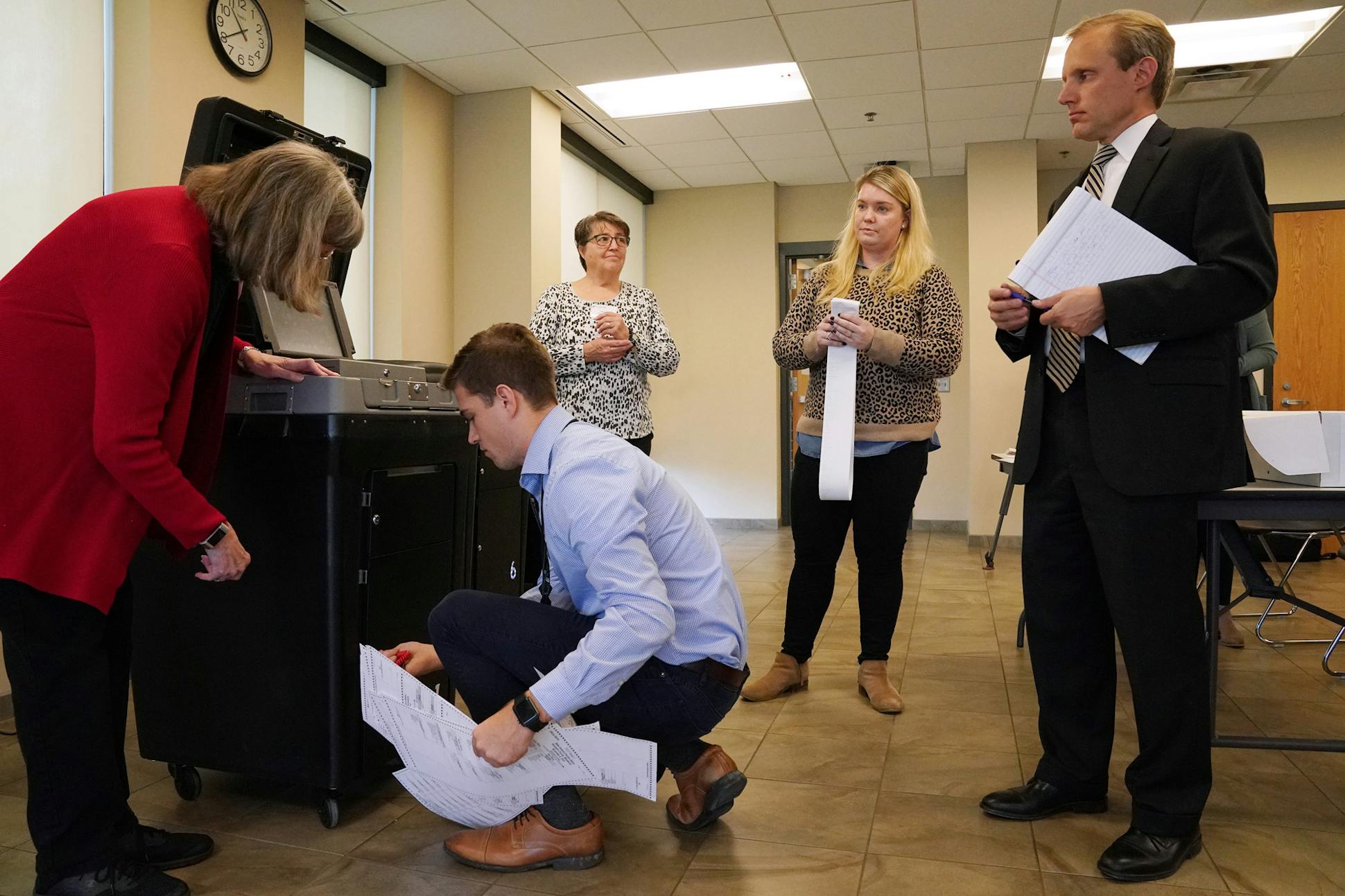

Crow Wing County is already required by law to both check the security of its voting machines before each election and to confirm that paper ballots entered into the machines matched the vote totals afterward. Both processes are open to the public.

Deborah Erickson, the county's administrative services director, said that the pre- and post-election public verification processes have historically been sparsely attended. She can recall just two people showing up to watch public pre-election equipment tests in her 25 years working on elections in the county.

Simon's office meanwhile is required to perform additional, random checks on counties' post-election audits. Crow Wing County was not selected in 2020, but Erickson said that such reviews hadn't uncovered any concerns in the past.

Both Simon's office and county officials such as Erickson are now privately considering how they can improve public awareness of measures already in place to verify election integrity in Minnesota. Failing that, they fear the creeping sense of doubt cast by many over elections could depress volunteers' willingness to help administer the vote in 2022 and beyond.

"We have been seeing recently — in the past few years — almost an eroding of the confidence people have in the election process without a lot of basis in fact," said Erickson, a nonpartisan county employee.

Familiar claims take flight

In an interview, Simon said he appreciated the balance struck by the board in maintaining faith in the 2020 election results while responding to "sincerely held beliefs to the contrary" voiced by constituents.

"That said, there is no legitimate reason to second guess the integrity of the 2020 election in Crow Wing County — and that's to the county's credit," said Simon, a DFLer, pointing to the work done by county and local election workers each year.

"We found it to be proper and precise and professional. There's no reason, 14 months after a general election, to somehow upend that election result."

Beyond Minnesota, the federal law enforcement and intelligence communities concluded that the 2020 election was among the most secure ever. And additional audits in states such as Arizona and Wisconsin — including some by Trump allies — have so far failed to find fraud at a level that would have altered the outcome of the vote.

The Crow Wing County activists, ranging at times from 75 to 100, brought with them familiar claims of proof that there were problems with the last election when they started stepping forward last fall.

Allegations included fraudulent Dominion voting machines — rehashing discredited theories put forward by Lindell and other pro-Trump associates. Others repeated false claims that an algorithm was used to control the outcome of the vote or that the amount of time it took for ballots to be returned to the courthouse from a given precinct was evidence of wrongdoing.

"We, us people in this room, have been disenfranchised by the evidence that we have seen," said Ben Davis, a pastor at the Remnant Ministry Center in Brainerd who helped lead the campaign. "It is overwhelming."

The group collected signatures for an online petition on the site auditcrowwing.com, which left open the possibility of demanding audits in other locations.

The website also encouraged visitors to sign an affidavit urging Minnesota legislative leaders to back a new election audit. It cited debunked claims from Lindell of evidence that votes were changed "over the internet" during the 2020 election.

'No, there wasn't an issue'

After months of discussion, Crow Wing County Attorney Don Ryan concluded late last month that commissioners had no legal authority to audit an already certified election. The board, in response, voted last week to ask Simon's office to conduct another review in their county.

Ryan added that he hadn't observed anything that made him question the integrity of the county's electoral system during his nearly three decades as its top attorney.

Crow Wing County Commissioner Steve Barrows shares that assessment and was the only board member to vote against the audit request last week. He said he could not support sending a message that suggested something was amiss in last year's election.

"These questions will never be answered to the satisfaction of this group 100 percent," Barrows said. "It also sends a message that there was an issue with the 2020 election — and, no, there wasn't an issue."

"I'm worried that our democracy, as we know it, going forward it seems to be under heavy pressure," Barrows added.

Commissioner Rosemary Franzen introduced the resolution asking Simon's office to audit the 2020 election in the county after Ryan's conclusion that the county lacked the authority to do so.

"I think restoring people's faith in our elections is an important thing and I think we need to support that," Franzen said last month. The resolution states that the board "continues to have faith in the 2020 election results as valid and reliable but it is equally troubling that there are citizens who still have a sincerely held belief that it was not."

Davis, a leader among the activists calling for an audit, suggested to the board last week that the group wanted to make sure "that the law is being followed and that fraud wasn't taking place in our county" rather than challenge the results of the election.

"This is what a healthy America looks like and I'm so grateful we get to exercise this freedom in this nation," Davis told the board.

'There won't BE any 2022..."

The campaign by some Minnesotans to start auditing elections again in Minnesota started before the Crow Wing County group took its concerns to their local government. Last September, thousands of Minnesotans eager to act on conspiracy theories about the 2020 election congregated on a channel dubbed "Minnesota First Audit Chat" that was hosted on the encrypted Telegram messaging app.

Seth Keshel, a former Army captain who claims to have statistical evidence of 2020 election fraud, implored his more than 152,000 followers on the app to e-mail state Rep. Dale Lueck after the Aitkin Republican stated he believed there was no evidence of widespread fraud in Minnesota's 2020 election. Keshel traveled to Brainerd last month to speak at an election conspiracy event that drew 300 people.

According to screenshots of a "First Audit" chat obtained by the Star Tribune, a user named Andy the Arrrrrgonaut who said he lived in Pequot Lakes, described an exchange with Lueck, who could not be reached for comment.

Lueck, the user wrote, told him he had received more than 300 e-mails about election integrity after Keshel's post. The user said Lueck told him he was interested in "cold, hard numbers."

"He also seems to think that if we get bogged down looking back at 2020, we'll lose sight of 2022 and 2024," Andy the Arrrrrgonaut wrote. "I replied that We The People are convinced that if we don't figure out what went wrong in 2020, there won't BE any 2022 or 2024."