Vanishing North

An occasional series in the Star Tribune documenting the biodiversity crisis and the people struggling to head off extinction for Minnesota’s most vulnerable animals and plants.

Jason Husveth felt sick to his stomach.

All the tensions and complexity of life rose as the ecologist raced from his home near Stillwater to the Blaine construction site. Behind the wheel of his greenhouse-gas emitting work pickup, he shot past the fields and trees giving way to more asphalt, more concrete, more lawns.

Road crews were already in full swing when Husveth pulled up. Mustard-colored bulldozers and backhoes roared back and forth on one half of the highway. Motorists zoomed by on the other.

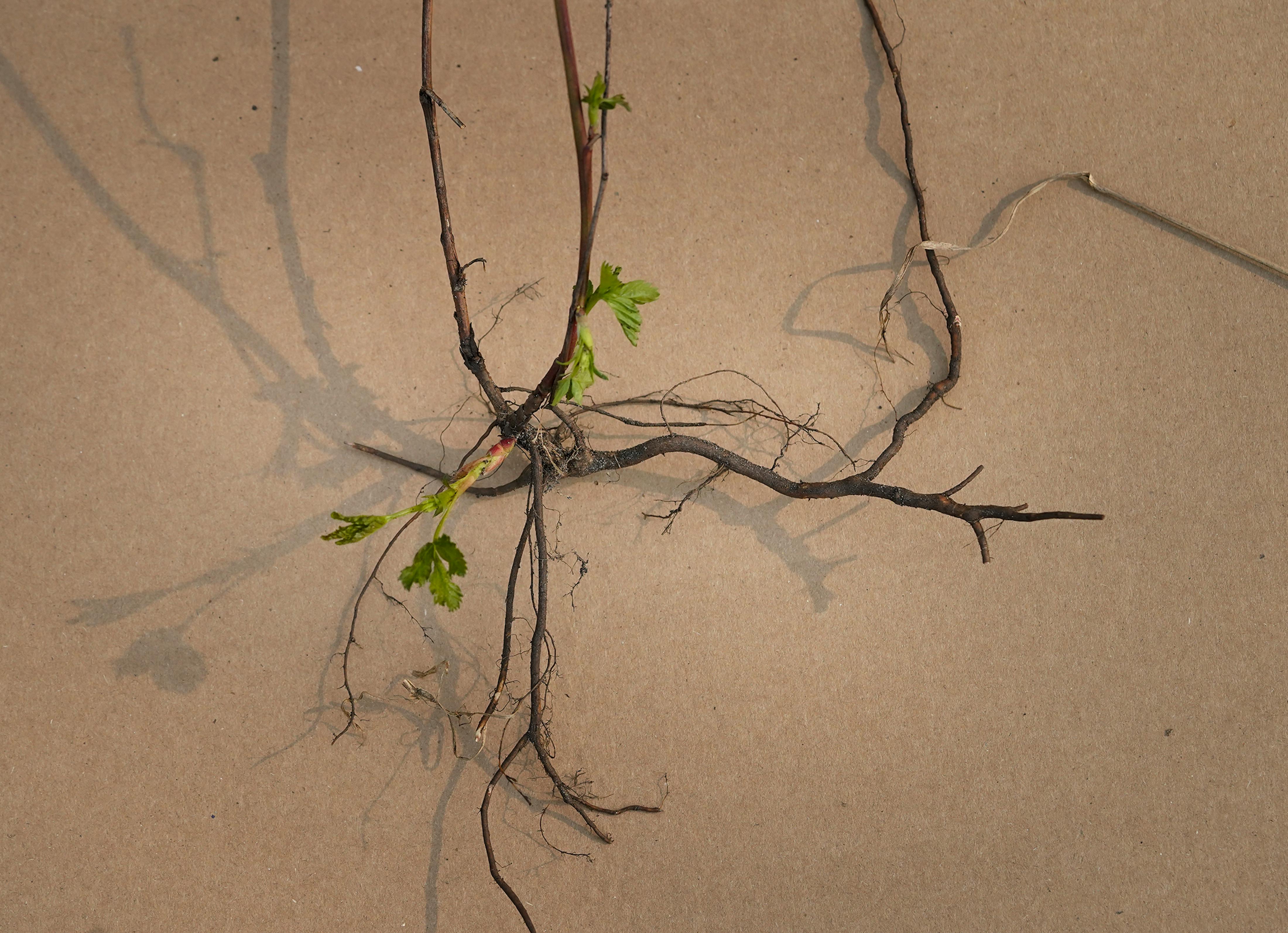

There, down in the ditch in a grove of aspen, was what Husveth and the others had come to save: bristle-berry plants. They looked like a bunch of bent reddish twigs someone jammed in the ground, their first leaves just sprouting.

Husveth grabbed his Sawzall. They had 48 hours to get these rare and endangered plants out so they at least have a shot at life. Native cousins of wild blackberries, the bristle-berries have existed in Blaine for thousands of years.

Now they are in the way.

The struggle to save Minnesota's biodiversity has come to this: a rescue squad for threatened native plants.

Across the state, Minnesotans are confronting what scientists are calling Earth's sixth mass extinction — and the first caused by humans. It might not be as cataclysmic as the asteroid strike that wiped out the dinosaurs and three-quarters of life 65 million years ago, said University of Minnesota ecologist David Tilman. But the extinction crisis is real, even in Minnesota.

Fifty species have been declared gone or likely gone from Minnesota, such as mountain lions, caribou, grizzly bears, the American burying beetle and a number of birds that no longer regularly breed in the state. At least 150 more are on the verge of disappearing, including the burrowing owl, goblin fern and piping plover.

Humans have been simplifying nature and thinning it out — creating a world that is far less stable and resilient, Tilman said.

Minnesota is losing species before we even know they are here. This year, the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) completed a 35-year ground survey to document rare species in every county. Now on the second cycle, state scientists are still finding species in places they didn't expect — including at least two varieties of moth they suspect are new to science, and an aquatic plant called pointed watermeal that is one of the smallest flowering plants in the world. No one knew it lived in Minnesota — a tiny rootless, stemless floating plant, like a bright green chubby grain of rice.

Across the state, people are taking extraordinary measures to save the rarest of the rare. Biologists at the Minnesota Zoo are using freezers to try to pull a tiny surviving population of a once abundant butterfly back from global extinction. Conservationists are making a tourist attraction out of the outlandish mating ritual of a native prairie bird surviving on patches of grassland. The Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe is working to guard a mushroom-like fern from the destructive invasion of earthworms.

The bristle-berries are an obscure victim, struggling to survive in ecosystems disrupted by farms, urban development, chemical pollution, invasive species and now a changing climate that threatens to turn Minnesota into Kansas. The pressures differ for each imperiled species. The No. 1 threat has been habitat loss and degradation, according to the DNR.

Few parts of Minnesota are changing faster than the hardening landscapes in and around Anoka County.

Last refuge under threat

Back in the ditch in Blaine, the plant rescue squad's immediate task was how to get 100 naked bristle-berry plants into the back of an old blue van without getting hit by traffic. Quickly. Plants don't like hanging around with their roots out.

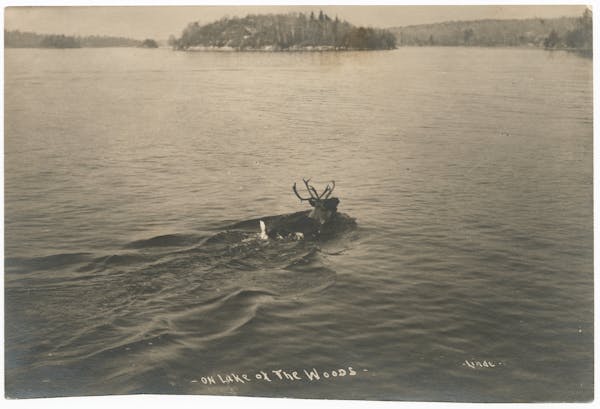

Bristle-berries emerged in the oak savanna ecosystem, less than 1% of which remains in Minnesota. Tracts of oak savanna hang on in the Anoka Sand Plain, a wedge of flat, sandy land that stretches from St. Cloud down along the north side of the Mississippi River and across the northern Twin Cities to the St. Croix River. It was formed by the slow grinding of glaciers and their meltwater as the ice receded some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

The Anoka Sand Plain is one of the last refuges for many bristle-berry species in Minnesota. The plants are named for the bristly stems, whose thorns are soft, not sharp. The habitat of Rubus stipulatus — the rarest and most endangered of Minnesota's 12 bristle-berries — once covered a million acres ranging into Wisconsin and Iowa. But no one has seen it in Wisconsin or Iowa for many years, said Minnesota state botanist Welby Smith, a bristle-berry authority who included them in his book "Trees and Shrubs of Minnesota."

Rubus stipulatus appears to survive primarily in the Anoka Sand Plain and almost nowhere else, Smith said. "The bristle-berries have hung on all this time," he marveled.

The fate of the bristle-berries matter not just because they represent the last of an historic landscape. They are valuable food for wildlife and carry cultural significance to Native Americans. And they could possibly benefit human health. Up to 60% of pharmaceutical medicines around the world contain plant compounds, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration says.

Even the most obscure organisms play an essential role in nature's functioning, even when we don't understand it. Smith uses a machine metaphor — an airplane, say, or a pocket watch with its various gears and springs: "You take one out… you don't know what's going to happen but you have a pretty good idea the watch isn't going to work as well as it did before," Smith said.

Husveth has combed the Anoka Sand Plain for some 25 years, a champion of this lesser-known landscape. It's his stamping grounds, the inspiration for half his life, he said.

"It just blows my mind that people want to say this species of plant is unimportant," said Husveth. "The plant nation literally is what gives us oxygen to breathe."

To him, the Anoka Sand Plain is an overlooked hotbed of biodiversity, with more than 100 imperiled species such as the eastern meadowlark, Blanding's turtle, the tubercled rein orchid and the slimspike three-awn, a type of grass no one knew grew in Minnesota until Husveth found it.

Many of the species survive in protected havens such as the Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve and the Carlos Avery State Wildlife Management Area. But just 1% of the Anoka Sand Plain is protected. Fast-growing cities and suburbs gobble land, squeezing nature into smaller and smaller pockets.

It's hard to even find healthy, protected habitat nearby to transplant the rare plants they salvage, said Carrie Taylor, the Anoka Conservation District restoration ecologist leading the new plant rescue program.

The Anoka Sand Plain Rare Plant Rescue Program is trying to outrace development to salvage and move rare plants. It's a partnership funded by the Outdoor Heritage Fund, between the Anoka Conservation District, the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum and Critical Connections Ecological Services, the Stillwater company run by Husveth and his wife, Amy.

They worked with the DNR to create a state permit for such rescues. Nearly two years in the making, the permit makes it legal for an approved party to take and propagate threatened and endangered plants, which are protected under the state's endangered species law. In the past they could not. If a developer with a permit showed they couldn't avoid the rare plants, they could destroy them after paying the DNR a mitigation fee.

Now there's an option. If the rescue group can establish a system for working with developers before ground is broken, the program could become a statewide model and save countless rare plants in the future, its leaders say. That's how they were able to intervene when Anoka County moved forward with its plans to widen the highway and build a new drainage pond in Blaine.

A rare flora survey confirmed bristle-berries were growing near the highway project, said Jason Orcutt, engineering program manager with the Anoka County Highway Department. Then Husveth was brought in. He counted about 500 bristle-berry plants in the project area, including about 130 Rubus stipulatus in imminent danger.

Orcutt said the county did its best to work around them, but couldn't move everything. And with just one lane in each direction, the highway cannot safely handle the growing volume of traffic. Crews are widening it, adding a concrete median and turn lanes, a bike and walking trail and better stormwater drainage.

This spring, the plant rescuers had been anxiously waiting for Orcutt's group to get its "take" permit from the DNR. When Husveth got word that the Anoka County Highway Department had the permit, the plant group sprang into action. Taylor shot off an email call for volunteers with the time and place.

"Protect yourself from ticks," she cautioned.

Down in the ditch that morning, the volunteers worked with speed. Husveth and others used Sawzalls and shovels to free the plants and surrounding soil. They placed the plants, roots exposed, in flat boxes in the grass.

If the rescuers can figure out how to coax them to grow in host sites, maybe they can prevent the plant from sliding toward extinction. It's not a sure thing. They have previously dug up lance-leaved violets and other bristle-berry species from the path of two housing developments — one named Nature's Refuge. Some didn't survive in their new home.

It's all an experiment, they keep saying. An urgent one.

Lost before properly found

Tilman, the University of Minnesota ecologist, estimates the world is losing species at a rate roughly 100 times what it was in the past. That's based largely on data about birds and mammals, he said, which are the most studied. For birds, the rate is closer to 1,000 times faster.

No one knows how quickly Minnesota is losing species because we don't know where we started from. The DNR's Minnesota Biological Survey and the University of Minnesota's Bell Museum of Natural History, with its Minnesota Biodiversity Atlas, are both building an inventory of Minnesota's native and naturalized species.

Both are incomplete. Insects are one huge gap.

Such fieldwork is a monumental effort. Minnesota may not be a global biodiversity hot spot like California. But it has a rich natural heritage reflecting the diversity of three North American biomes that meet in the state: the eastern broadleaf forest, the prairie and the northern boreal forest.

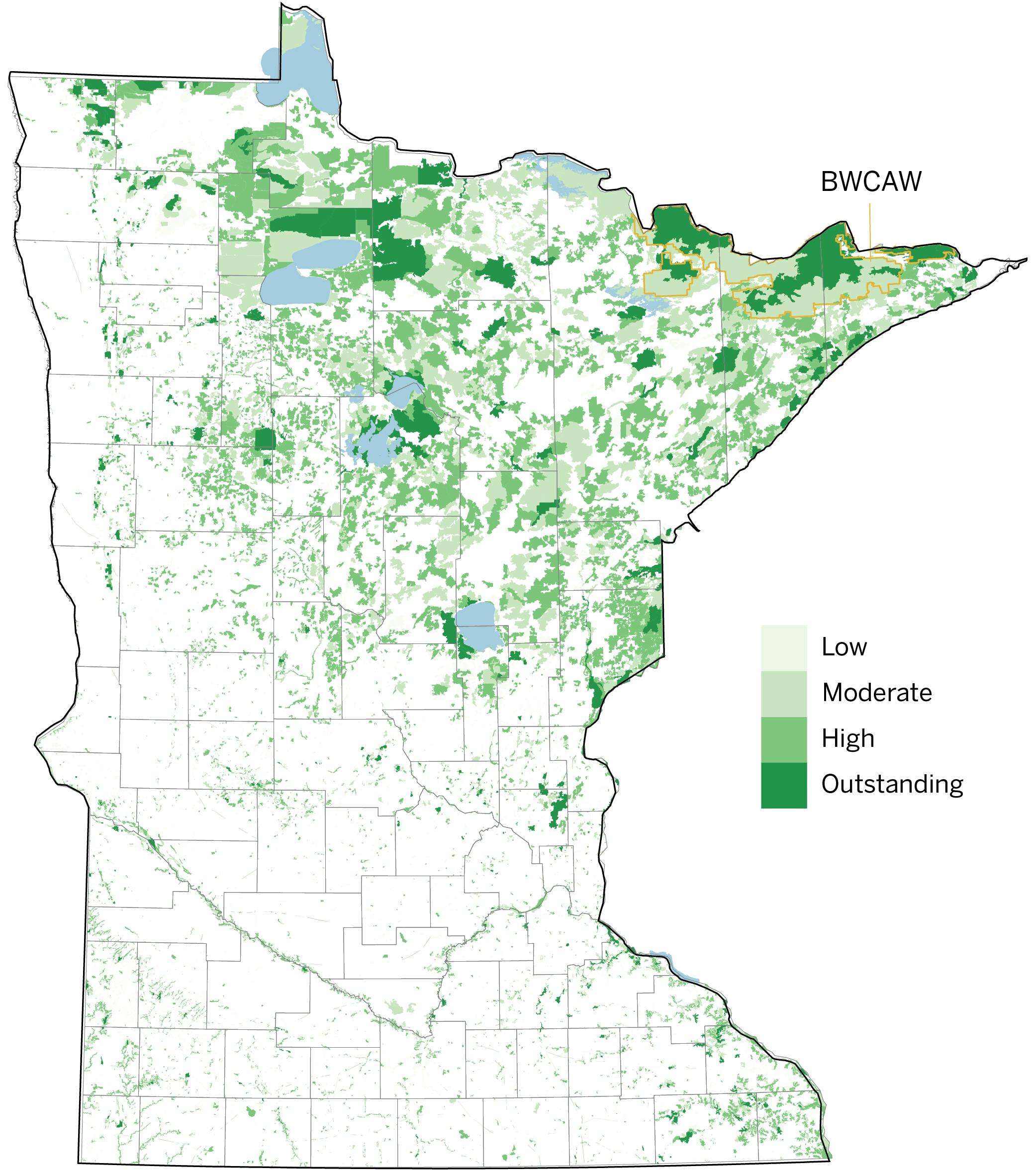

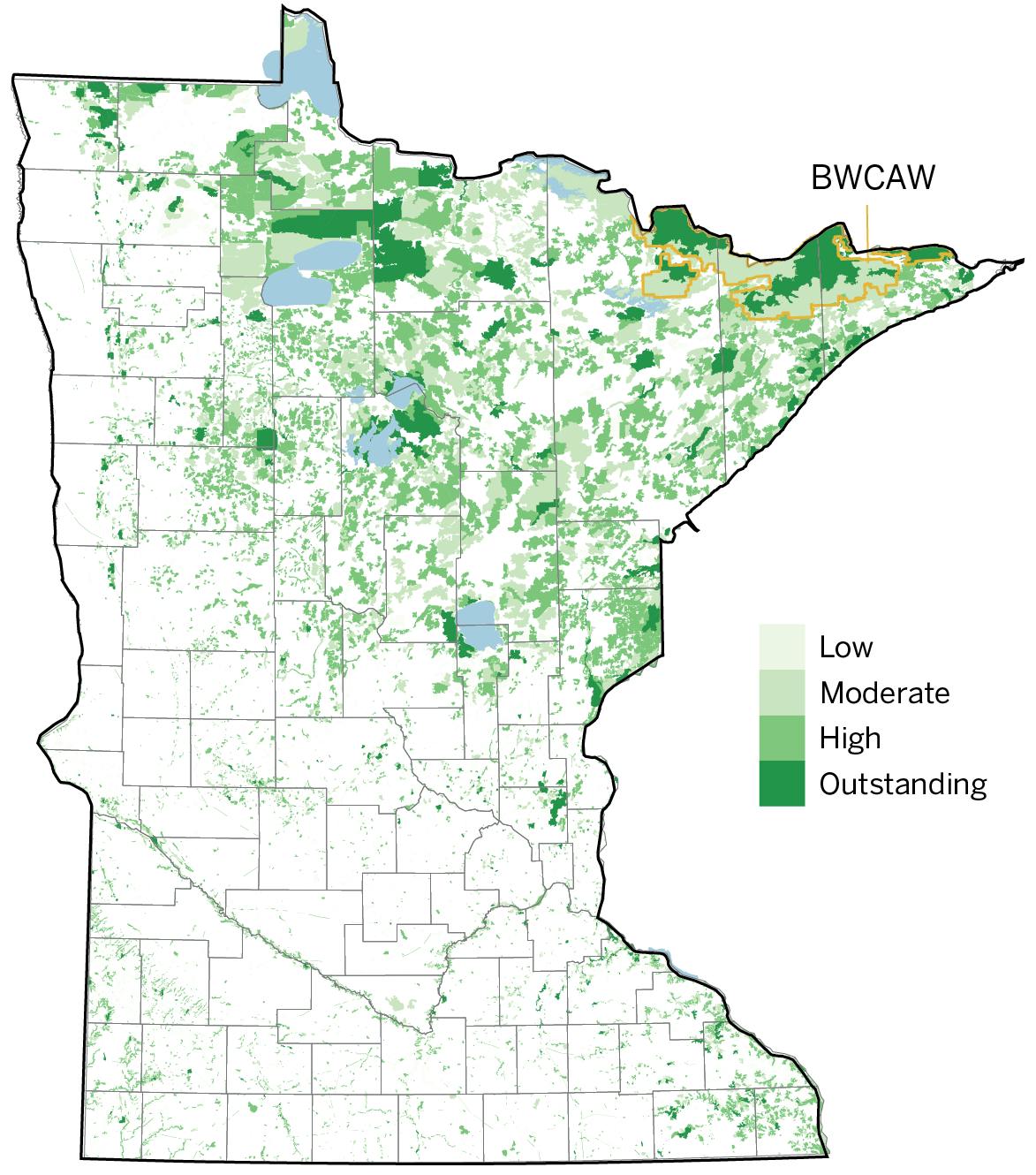

Yuqing Liu, Star Tribune • Source: Minnesota Biological Survey, State Department of Natural

Resources

Yuqing Liu, Star Tribune • Source: Minnesota Biological Survey, State Department of Natural

Resources

The DNR's Minnesota Biological Survey is already on a second pass through the state to fill gaps and focus more on monitoring change, said Bruce Carlson, the plant ecologist who runs the survey from his cramped corner cubicle in the DNR's St. Paul headquarters.

As Carlson sees it, the statewide biodiversity picture for Minnesota isn't one of total collapse, but slower demise. The species already pushed out — like caribou and whooping cranes — are victims of at least two waves of recent die-offs. The first followed the arrival of Europeans in Minnesota, when French fur traders in the 1600s hunted down beavers, otters and mink. The second was the global "great acceleration" following World War II when human impacts on the environment began to soar.

The true number of species driven to state-level extinction is no doubt higher than what has been documented, Carlson said. Not only are scientists loath to declare something gone, the state lacks a full account of all species that live here.

Many, many more species, such as the bristle-berries, are clearly in trouble. A full 591 species are state-listed as endangered, threatened or of special concern — an account last updated in 2013. That's double the 287 listed in 1984. The rise is explained in part by better data, but also speaks to relentless pressures undermining species' survival, Carlson said.

For plants, the final stop for the DNR's specimens is the University of Minnesota's Herbarium. There, in a room on the 8th floor of the Biological Sciences building on the St. Paul campus, stand rows and rows of hulking cabinets.

George Weiblen, the museum's director and curator of plants, locates the bristle-berry records in seconds. Pressed on paper in a file is a flattened Rubus stipulatus specimen, crisp and brown. He sticks his thumb over the specimen's location when he holds it up for a snapshot. Under Minnesota law, the exact location of a rare species must be withheld from the public.

The loss of a species like the bristle-berry goes beyond a statistic in a university survey or its effect on an ecosystem. It's a blow to human culture as well.

The black fruit of the bristle-berries ripens in August. They're part of what Dana Thompson, co-owner of Owamni restaurant in Minneapolis, calls the vast edible landscape that sustained Native people.

"I can tell you if it was edible, the Indigenous people would have watched animals eating it first, and then they would have done their own testing within the tribe," said Thompson. "All berries are medicinal."

Thompson said she's heard of bristle-berries because North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems, or NATIFS, the nonprofit she founded, is creating an instructional berry book for tribes. Bristle-berries didn't make the cut, she said, but such foods are loaded with cultural meaning. Destroying the food system was a key way that the U.S. and Canadian governments tried to wipe out Indigenous peoples, she said.

Linda Black Elk, an ethnobotanist at United Tribes Technical College in Bismarck, N.D., said the berries have "an intense blackberry flavor." Black Elk said the leaves are used for sore throats and ulcers, and the berries are dried and cooked for wojapi, a traditional Dakota dish of berry pudding or soup often made with chokeberries, huckleberries, blueberries and blackberries.

It's crucial to protect such plants, Black Elk said. When even one food source disappears, a whole set of medicines and culinary traditions can slip away with it. People can switch to a cultivated blackberry, Black Elk said, but "it's not really the same."

Black Elk suggested the bristle-berry salvage and restoration effort might be worthy of a ceremony to mark its significance.

Taking solace in the little victories

The workers in the ditch in Blaine ignored the trash littering the ditch, and avoided the fluttering red and yellow flags marking the routes of gas lines and cables. By the end of the morning, they had dug out about 100 plants. Amanda Weise, conservation botanist at the Landscape Arboretum, was taking plant cuttings to cultivate as backups.

Holding a box of plants, she described the rescue as "emotional chaos." They all know that being better stewards of the land, not moving plants from one place to the other, is the ultimate solution.

"We know it's something," Weise said about their work that morning. "It buys us time."

The spot where she stands will soon be unrecognizable. One part of the old berry patch will become the edge of a new drainage pond being engineered out of the little wetlands. Another part will probably be buried under feet of aggregate for the shoulder of the widened road and topped with asphalt. Nothing will ever grow there again.

The volunteers loaded the van and drove the homeless plants one suburb over to Bunker Hills Regional Park, a 1,600-acre park with about 280 acres of open oak savanna plus wetlands. It has become a laboratory for the plant group, one of several protected areas that Taylor, the plant rescue program's leader, scouted out with the county's parks department.

A dozen volunteers have shown up dressed to work. Under trees near the parking lot, they cleaned weeds from the plant roots and checked for destructive jumping worms as they chatted.

Jacob Cunningham, a St. Paul dad wrestling with some plants, said he was surprised that he'd never heard of the Anoka Sand Plain before. He said he's working on a master's degree in environmental education and loves the idea that you don't have to drive hours north to experience some wild habitat.

"Wow, we have this priceless ecosystem in need of protection," Cunningham said.

Taylor led the volunteers to a spot next to a wetlands near some shrubby meadow willows. It has just the right soil, she explained: a sandy, silty loam that holds water. A series of quadrats — plots framed with 1-meter squares of white PVC tubes — clearly marked where the plants should go.

They kicked spades into the ground and planted the bristle-berries about one foot apart.

Husveth noted that it's peatland, likely drained long ago for use as a cow pasture. He pointed to old fence posts. It's overrun with reed canary grass now. The aggressive, emerald-green invasive plagues the sunny wetlands it loves where its dense root mass chokes out other plants.

On a small notepad, Taylor noted the exact location of the plants for the DNR so the transplants aren't mistaken for a natural colony.

Around noon they wrap up and head out. The bristle-berries are safe for now. With luck they will survive, maybe even form a thicket.

Upbeat, Husveth said he was heartened by all the people who dropped what they were doing on a weekday to help save a plant most of them had probably never heard of.

The group will reconvene for the next rescue, when the next developer gets a "take" permit. That will probably involve two other threatened bristle-berry species in the path of a housing development in Andover.

As Husveth sees it, there's a been a shift in public attitudes toward plants, natural areas and the importance of biodiversity. It's driven by the growing awareness of climate change, he said. To make his point, he gestured around at the park bursting into life. The county's park system is changing, he said, fostering more wild areas instead of hardscapes.

"The tide is turning," said Husveth. And he turns toward his pickup for home.

Staff writer Greg Stanley contributed to this report.

Share your story

Please share feedback, questions and suggestions by using the form below. Our reporters will not share your information without your permission. Thank you.

Correction: An earlier version of this story mischaracterized the consequences of a developer with a take permit destroying rare plants. They can destroy the plants after paying a mitigation fee to the DNR.