Today many disabled Vermont residents are thriving in the community – and the state is saving money.

MIDDLEBURY, VT.

In the basement kitchen of a stone church nestled in the Green Mountains, Rachel Wollum studied her reflection in an oven window, adjusting her auburn hair and orange polka-dot dress until they were just right.

Satisfied with her appearance, Wollum, who is 26 and has Down syndrome, carefully poured four trays of freshly baked chocolate chip cookies into bags bearing her name. Then, with the intensity of a drama student, she rehearsed lines familiar to almost every store clerk in Middlebury, where "Rachel's Cookies" are now a household name.

"Hi, my name is Rachel, any cookies today?" she said. "Great, thank you so much for serving my cookies. Have a beautiful day! You're welcome!"

With her zest and ambition, Wollum personifies the remarkable strategy that has made Vermont a leader in the civil rights movement for adults with disabilities. If she lived in Minnesota, Wollum might have been steered into a sheltered workshop or mobile cleaning crew, where thousands of disabled adults perform mundane tasks and have little or no contact with the broader community.

But here, in this state of hardscrabble hillside farms and country roads lined with sugar maples, sheltered workshops are a thing of the past. Disabled adults are expected to take their place each day alongside other working people. In the 16 years since the U.S. Supreme Court ordered states to end the segregation of people with disabilities, few states have carried the flag as boldly as Vermont.

"The days of hiding people away in closeted boxes where you could no longer see them or think about them — those days are over here," said Pauline O'Brien, 80, whose cognitively impaired son, Sean, worked at a sheltered workshop for 23 years. "And we're never going back."

In 2002, Vermont became the first state to stop funding sheltered workshops. The state also ended the practice, still common in other states, of using Medicaid to subsidize group homes for people with disabilities.

Instead, the state sends money directly to disabled clients for services of their choosing, such as job coaching and transportation.

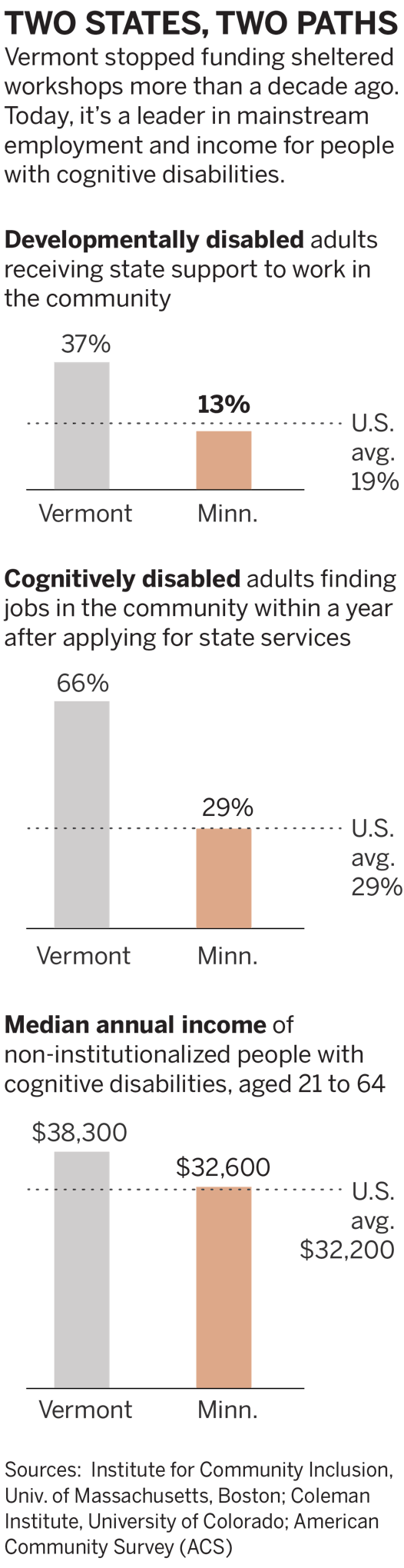

Today, Vermont leads the nation in almost every measure of workplace inclusion. Vermonters with intellectual disabilities are twice as likely to find jobs in the community as their counterparts in other states. Nearly 40 percent work in the community alongside people without disabilities, compared with 13 percent in Minnesota.

"In Vermont, they imagined a system focused on the empowerment of individuals, rather than institutions, and they achieved it," said John Butterworth, director of the Institute for Community Inclusion at the University of Massachusetts, a research center on developmental disabilities. "They proved it can be done."

A shameful history

When Bill Villemaire looks back on the 36 years he spent toiling in a sheltered workshop in the town of Colchester, he remembers the daily ringing of the cowbell.

Each morning it signaled the huddled crowd of developmentally disabled workers that it was time to march downstairs to the assembly line. There, Villemaire would spend hours in a windowless basement, performing rote tasks such as inserting wires into air ducts, until the cowbell rang to mark the end of his shift. He made as little as $2 a day.

"I wanted to destroy that cowbell," said Villemaire, 59, who now makes $10 an hour stocking shelves in a neighborhood grocery store. "They treated us like animals. … It was soul-draining."

Though famous for maple syrup, Ben & Jerry's and picturesque ski resorts, Vermont has a long, dark history of segregation and abuse of people with disabilities. Memories of that era still hang like a shadow over those who experienced it.

As recently as the late 1980s, Vermont housed more than 500 people with disabilities at a sprawling west Vermont campus once known as the Brandon Training School. Here, in brick buildings where weeds now curl out of shattered windows, so-called "mentally deficient" adults were often beaten and tied down with restraints.

A lawsuit filed by one of the residents, Robert Brace, coupled with public outrage, led to the facility's closure in 1993 and marked the beginning of Vermont's revolution.

More than two decades later, Brace, now 55, struggles to contain his anxiety as he recalls his 17 years at Brandon Training School. His fingers twitched and his eyes glanced nervously at the ceiling as he recounted being placed in a straitjacket and given shots of psychotropic drugs when he "acted out." To ease his anxieties, a therapist gently touched Brace on his hands, arms and face — a therapy known as "tapping" — while speaking soothing words.

"Robert, you're OK now, you're safe," said his therapist, Al Vecchione. "Don't worry. You're never going back to that horrible place."

New alternatives

The effort to close sheltered workshops met stiff resistance, largely from parents who feared their children would be stuck at home, idle and bored. That group included Dottie Fullem, 89, who was among a handful of parents who founded a workshop known as Champlain Industries with the best of intentions.

As a working mother in the 1960s, Fullem had no place to send her daughter, Ann Marie, who has a developmental disability, after she graduated from high school. At the time, the workshop seemed like a safer, more humane alternative to a state institution.

"It was a dull and dreary place," recalled Fullem of the workshop. "They treated my daughter like a fixture on the wall." Still, she said, the workshop was "a safe place to go, a place where she could stay busy and make friends."

But parents like Fullem discovered that Vermont could do better. Starting in 2001, the state redirected its money, from workshops to individuals. Hundreds of people who once labored in workshops for as little as $1 an hour now make at least minimum wage and receive stipends to pay for their own job training and transportation, among other services.

Vermont also centralized job services, rather than farming them out to counties as Minnesota does, and hired "community inclusion facilitators," who carve out jobs for clients by making visits to local employers.

"If someone can work in a sheltered workshop, then they can work somewhere else," said Ric Wheeler, a manager at the Counseling Service of Addison County in Middlebury. "What's so special about a sheltered workshop? They're doing tasks. They're showing up." Laughing, he added, "That's what you do at work, right?"

The push for inclusion starts early. College students with developmental disabilities can receive mentoring from fellow students, who attend classes with them and connect them with campus activities. Nearly 90 percent of students who participate in the program find jobs in the community upon graduation.

Kate Daly, 29, who has Down syndrome, is among them. In high school, Daly found herself stuck in a part-time job bagging groceries at a supermarket in her hometown of Rutland. But with help from a state-funded mentor, she earned a certificate in business and now works as front desk manager at a health and wellness studio in Rutland, where she greets customers and leads dance classes.

"I told my mom, 'I am absolutely not going to spend my entire life bagging groceries,' " Daly said. "Now, I have my dream job."

In Middlebury, Wollum runs her cookie business with support from a state-funded job coach. She buys ingredients at a local grocery store, bakes and delivers the cookies, and deposits her daily receipts at a bank near her apartment. Wollum, who converted to Catholicism after high school, donates most of her profits to St. Mary's Catholic Elementary School, which lets her use its kitchen.

"I do all this!" she said proudly, as she rolled cookie dough. "I am the baker and the operator."

The "Vermont model'' of supported employment has thrived. Within three years, 80 percent of the employees at the state's last sheltered workshop had found paying jobs. It has the highest rate of community job placements for clients with developmental disabilities; in 2013, its rate was nearly six times the national average.

Few places embody Vermont's transition like Champlain Community Services, a bustling job center near Burlington. On a bright morning in June, people who 15 years ago would have worked at a sheltered workshop here poured in for advice on everything from opening a bank account to asking for better pay.

Among the visitors was Jay Lafayette, 42, who announced that he had just gotten a $2-an-hour raise cooking and serving food at the local baseball stadium. He clutched a packet of John Hancock 401(k) retirement pamphlets, asking about where to invest. It was a dramatic about-face for a man who remembers being dragged and beaten at Brandon Training School when he was a youth.

"I never imagined in my wildest dreams that I would have a future like this," Lafayette said later as he served fries at a Vermont Lake Monsters baseball game in Burlington.

The benefits of 'hard work'

It was late morning when Tiffany Plamondon, 26, rolled her wheelchair, laden with art supplies, into a gift shop on Main Street in Bradford, a sleepy town on Vermont's eastern border.

Outside, the air was foggy and cold. But the store was warm, and Plamondon, who has cerebral palsy and limited use of her limbs, was already working up a sweat. With the help of a social worker, Plamondon strained to communicate which of her colorful greeting cards would be sold in Vermont stores ahead of the July 4th weekend. A wide grin or a grunt signaled a "yes." Silence or a roll of the eyes usually meant "no."

By pressing her head against a mechanical lever, Plamondon can trigger a series of prerecorded sales messages through a voice synthesizer attached to her wheelchair. Even now, two years after launching her card business, she struggles a bit to make the device work.

"I don't want anyone to get the impression, for a single second, that this is easy," said Lisa Culbertson, manager at Upper Valley Services in Bradford, as she helped Plamondon adjust the voice synthesizer. "Figuring out what works for Tiffany is hard work."

Nonetheless, the payoff for taxpayers is sizable. Since 2005, Vermonters like Plamondon have paid $11.9 million in payroll taxes and, by working, have reduced outlays on Social Security disability and other entitlements by $5.5 million, according to state figures. The public funding is also highly efficient: In Vermont, 61 percent of people with disabilities find work in the community within a year after receiving state employment supports, more than double the rate in Minnesota and the rest of the country.

The fiscal benefits have been a crucial selling point in this small but politically complicated state.

"This issue is a bit like Switzerland — it's neutral territory," said Elizabeth Sightler, executive director of Champlain Community Services in Colchester. "The notion of inclusion … appeals to just about everyone, regardless of their political stripes."

Warm cookies all around

Back at St. Mary's Church in Middlebury, Rachel Wollum was performing a victory dance. With her hands outstretched, she hopped around the church kitchen with her father, Joel Wollum. "Woo-hoo! Hooray!" she yelled, circling the room.

The cause for celebration was a handwritten note from the church secretary, now clutched in Wollum's sweaty palm, announcing that nearby Middlebury College had called to say it would sell her chocolate-chip cookies in the college bookstore. The order might double her cookie business, and meant she might have to hire someone to keep up with demand.

There was, however, little time to celebrate. Across Middlebury, small businesses, from a local tire store to the Ford dealership, awaited Wollum's daily delivery.

"OK, we're ready to roll," yelled her delivery driver from an SUV idling in the church parking lot.

"Let's make some money!" Wollum yelled back, darting out the door with a wicker basket full of still-warm cookies.