This time, however, Dalluhn was the one requesting the hearing. She wanted the Dakota County judge’s approval to sell $60,135 in settlement payments she was due to collect in the coming years.

The Florida company buying the payments estimated they were worth $51,771. Dalluhn, who suffered a traumatic brain injury and spinal fracture after being struck by a car in 2014, had agreed to sell them for $24,129.

It wasn’t the first time Dalluhn had tried to sell her payments. A different Dakota County judge had rejected a virtually identical deal just two months earlier, noting in her order that Dalluhn “testified that she suffers from a mental health condition, has been civilly committed four times and is under civil commitment now.”

At her January 2020 hearing, however, Dalluhn’s mental health problems were dispensed with quickly,

according to a transcript of the proceedings. Judge Carter asked if Dalluhn was still taking her court-ordered medications and seeing her therapist. Dalluhn said she was.

A day later, Carter approved the sale. The following month, he extended her civil commitment for another six months, finding her mental problems were still serious enough to require close supervision.

Carter declined to discuss the case, but in his order he concluded Dalluhn had the “mental capacity” to enter into the agreement. Dalluhn’s mother disagrees.

Laura Dalluhn held a school project her daughter made for her for Mother’s Day.

“She is very vulnerable,” Mary Jo Dalluhn said. “And they know that. When you are talking to someone who is living in a psychiatric ward, you know that person is mentally not able to be making those kind of decisions.”

Across the country, local judges have the final say on whether companies can buy settlement funds paid to individuals, many who have experienced devastating, lifelong injuries. They can reject deals if they believe the terms are unfair, or if they believe the sellers lack the ability to understand what they are giving up.

But it is a power that judges are often reluctant to wield.

In Minnesota and most other states, laws on the sale of structured settlement payments provide judges with no guidelines on what may or may not be in someone’s best interest, no limit on the profit companies can make on a sale, and no restrictions on how often someone can come to court to sell their payments.

About 750,000 people in the U.S. receive structured settlement payments, and each year thousands of them sell an estimated $1 billion worth of future payments for smaller lump sums of cash. National data was unavailable, but industry sources say overall volume was down in 2020, primarily because courthouses were closed for months in some states, slowing the pipeline of pending deals.

In Minnesota, judges say they are routinely deprived of key information about the people selling their payments, including medical records and court filings that might provide insight about their cognitive ability or mental competency.

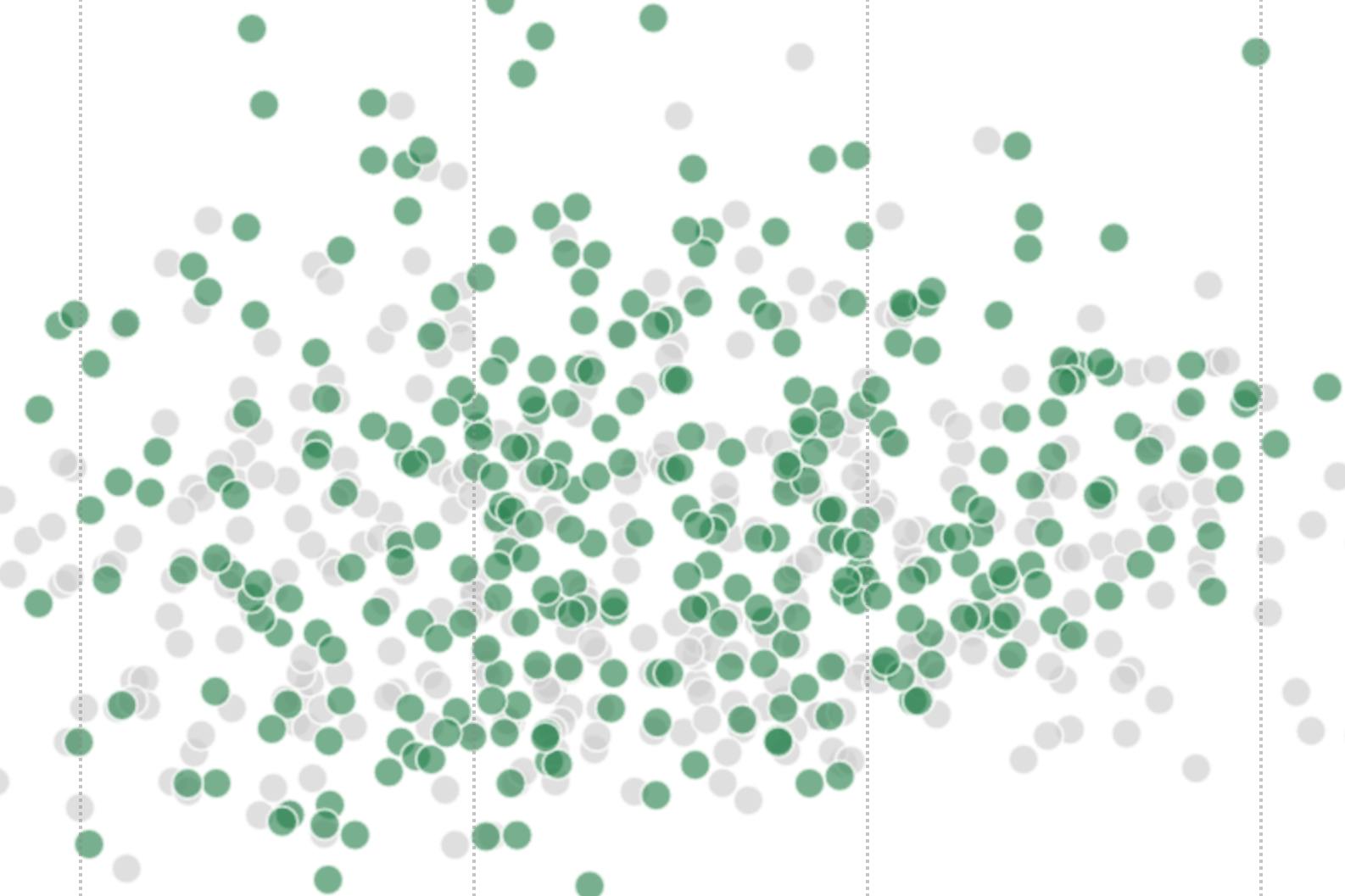

Meanwhile, companies have successfully sought removal of some judges who have rejected sales or questioned the lopsided nature of deals in past cases, according to the Star Tribune’s review of more than 1,400 Minnesota cases that have gone to a hearing since 2000. Such maneuvers are legal in Minnesota and require no supporting evidence.

“I hated these deals, but it was hard to say ‘no’ because everyone else was saying ‘yes,’ ” said former Hennepin County Judge Ann Alton, who handled about 100 settlement cases before retiring in 2014. “I brought it up at bench meetings, but nobody wanted to get into it.”

Executives with companies that buy the payments argue that Americans should have the freedom to make their own financial decisions. They defend the approval system, saying judges have all the authority they need to protect people.

If judges are concerned that someone trying to sell their payments is mentally incompetent, or “immature” or “unsophisticated,” they can appoint a guardian or “simply deny the deal,” said Earl Nesbitt, former executive director of the National Association of Settlement Purchasers, a trade group that represents 10 companies that buy settlement payments.

In Minnesota, judges approved 90% of the deals that have gone to a hearing since 2000. A guardian was appointed in just one of 1,725 cases reviewed by the Star Tribune.

Judge Joseph Carter

In an interview, Laura Dalluhn said she was still confined in a Minneapolis mental institution when a sales representative from Florida-based Greenwood Funding talked to her about selling her payments. She said the representative told her that “she had bipolar disorder, too.”

“They are kind of like vultures,” Dalluhn said. “It felt very aggressive to me.”

After the first judge rejected the deal, Greenwood redid the contracts and filed a new request under the name of an affiliate, Sempra Finance, interviews and court records show. Greenwood officials did not respond to requests for comment, and an attorney for the company also declined to discuss the deal.

Though he refused to comment on Dalluhn’s situation, Judge Carter said in an interview that the courts should find a way to routinely appoint a guardian or some other neutral party to advise judges on whether a deal is really in a seller’s best interest.

“It is a good idea for someone in these cases … to have the petitioner’s interests at heart,” Carter said.