Relentless tactics target wary sellers

Firms go to great lengths to find people who receive settlements, swamping them with checks, calls and ads even after they've agreed to sell. The payoff is high.

Kenneth Jennings, who sold parts of his $4 million settlement, has had to cut back on caregivers. Here, friend Leslie Skipper says goodbye after a visit.

It did not take long for the phone to ring the first time Brandon Kaczmarek sold a portion of the legal payments he was due from a childhood tractor accident.

A sales representative from J.G. Wentworth was on the line the next day, with a question: Was the Hutchinson, Minn., resident ready to sign over more of the payments he was due from his court settlement?

"I said, 'Dude, I sold you $40,000 yesterday!'" Kaczmarek said.

Each year, companies such as J.G. Wentworth, DRB Capital and Novation Settlement Solutions buy an estimated $1 billion worth of payments from people who have received a legal settlement, often because of a personal injury or medical malpractice event that resulted in lifelong injuries or other health problems. There is no readily available list of people who receive a structured settlement, so companies go to extraordinary lengths to find them. They comb court records and spend tens of millions of dollars on television commercials, for premium placement in online search results and on direct mail.

Once found, the people face relentless pressure to sell again and again. The payoff for companies is lucrative.

In Minnesota, 25 people accounted for nearly 20% of all settlement payments sold since 2000, according to a Star Tribune analysis of about 1,700 settlement purchases over the last two decades. Industry leader J.G. Wentworth has gone to court 13 times since 2010 to buy payments from a 58-year-old Washington County woman. A former hockey player from the University of Minnesota did six deals with four companies from 2004 to 2019, selling more than $900,000 in future payments he was due to receive for a foot injury that ended his career.

Companies are often able to get repeat customers to accept smaller returns on their money in subsequent sales — even when those future payments are guaranteed. People agreed to worse terms than their original deal in more than two-thirds of the cases reviewed by the Star Tribune.

That's what happened to Kaczmarek, who as a child was so badly burned over much of his body that he had to wear a mask and tights on his legs for two years. He dropped out of high school and was unemployed and living in his car — but sitting on an annuity that would pay him almost $1 million over the course of his life — when he first saw a commercial for J.G. Wentworth.

For his first sale in 2010, Kaczmarek received 77% of the present value of the payments. For his fifth sale in 2017, J.G. Wentworth bought $80,000 in payments for $28,000, meaning Kaczmarek received about 48% of the present value of those payments.

After a judge approved Kaczmarek's first sale, Wentworth's competitors swung into action. He still gets as many as 10 to 12 calls a day, sometimes beginning as early as 7:30 a.m., from companies offering him a cash advance on payments he will receive through 2047.

He has begged to be placed on do-not-call lists and has changed his phone number several times. But the companies always find him.

"It's that crazy," Kaczmarek said. "They pressure you and pressure you."

The sales effort begins in county courthouses across the country.

Unknown to people who receive settlement checks, companies that buy those payments employ an army of researchers to plow through court records. They are on the lookout for cases that usually end with a large settlement rather than a trial: serious car crashes and medical malpractice claims, or wrongful death and large class-action lawsuits, such as those involving asbestos or lead paint poisoning, where the victims might number in the hundreds or even thousands.

Wentworth, in a 2014 filing with regulators, said its database of 122,000 current and prospective customers represented "$32 billion of unpurchased structured settlement payment streams."

Chris Milton, president of Catalina Structured Funding, said his California company sends out thousands of fliers each week. In March, a Minnesota customer received three realistic-looking checks totaling $4,500 in so-called "90-day Covid-19 Assistance" from the company. On the back of the checks, Catalina noted that the funds are actually an "advance" that would be released only if the recipient signed a contract selling some of his future payments to the firm.

Milton said it took years for his company to build a database of about 40,000 potential clients.

"It is incredibly expensive," he said. "Think about it — how many counties are in the country?"

Names, ages and terms of the settlement, if available, are entered into proprietary databases. Sales agents work those databases hard. A training manual from another company, Maryland-based Access Funding, instructed agents to call potential clients nine to 10 times a day for at least three days after making initial contact. The manual was turned over to federal officials in 2019 as part of an ongoing civil case against the firm.

"In addition to calling them relentlessly, you must also be texting them, e-mailing them and trying to find them on social media, like Facebook," the manual said. "The bottom line is that the more touch points you have with the lead, the higher likelihood that you will eventually make contact, build a relationship, close deals and make money."

The companies that buy settlement payments argue that they provide a valuable service to people who are locked into agreements that pay out over years, even decades. By converting a portion of those payments into a lump sum, their customers can pay for college, make a down payment on a house, or get out of debt.

If finding prospective customers is hard, the business model is relatively straightforward: Pay as little as possible for payments that are both guaranteed and tax free.

Chicago resident Kenneth Jennings was paralyzed after breaking his neck playing high school football. He received a settlement valued at $4 million.

"I grew up as a kid in the projects — $100 was huge for me," Jennings said. "And all of a sudden I had all of this money in my lap."

When buyers contacted him about selling some of his payments, Jennings said he was too young and unsophisticated to understand what he was giving up. Since 1998, a handful of large players in the business, including Novation and Peachtree Settlement Funding, have bought about $2 million in payments from Jennings. He said he received about $500,000.

Most of the money went to medical expenses, such as 16-hour-a-day caregivers, he said. There were also big hospital bills.

"I've had pneumonia 12 or 15 times, and I was in the hospital for a couple of months for reconstructive elbow surgery," Jennings said. "That all came out of my pocket."

Every time a company persuaded Jennings to sell a stream of future payments, his financial safety net weakened — something Jennings said he did not realize at the time.

Today, he is living with the consequences. He should be getting monthly payments totaling more than $14,000 this year, but instead his deals have chopped that income to about $4,100. He was forced to cut back on his use of caregivers, and he had to get rid of his van after the lift broke.

"My whole way of life is different from what it should be," Jennings said. "I can't travel like I want to. I am not able to take care of my daughter the way I want to. It's a struggle."

In 2016, Jennings and other Peachtree customers in Illinois filed a lawsuit against the company's corporate parent, J.G. Wentworth, saying sales agents for the two firms misleadingly portrayed them as competitors when they were shopping around for the best deals on their payments. As a result, they said they had been tricked into accepting "paltry" amounts of money for their payments.

J.G. Wentworth denied any misrepresentations in a legal filing. The case was dismissed after an Illinois judge noted that the contracts signed by Jennings and other plaintiffs included binding arbitration clauses.

John McCulloch, a Chicago consultant who helps insurers and lawyers set up these structured settlement packages, estimates that 70% of the settlement purchasing industry's business comes from repeat customers.

He likens companies that buy the installment payments to drug dealers and has proposed mandatory "speed bumps" that would restrict settlement recipients from selling payments more than once every two of three years.

"Once they know who you are," he said, "they swarm until there's nothing left."

The business of buying settlement payments started almost by accident in 1989, when a real estate developer in Dallas, Jim Lokey, responded to an ad in a local newspaper from a man who wanted to sell his future payments for a lump sum.

Lokey eventually formed Settlement Capital and set out to find more people who might want to sell their payments for a lump sum of cash, a business now known as factoring.

"All of a sudden we were getting referrals from all over the country," Lokey said.

Competitors, including J.G. Wentworth and Stone Street Capital, entered the business (Wentworth later bought Stone Street). A trade group, the National Association of Settlement Purchasers (NASP), formed in the mid-1990s. Today, it counts 10 corporate members — seven of them are located within a 50-mile stretch north of Miami.

One, Novation Settlement Solutions in West Palm Beach, claims it has purchased $1.5 billion in structured settlement payments since 2000. Another, 123 Lump $um, says in a promotional video on its website that it has bought $250 million worth of payments since 2010.

But there are dozens more that are not members of the trade group, including the biggest, J.G. Wentworth, headquartered in suburban Philadelphia. Wentworth says it has purchased more than $9 billion worth of settlement payments since 1995. In Minnesota, Wentworth or Peachtree were involved in more than half of all settlement purchases identified by the Star Tribune since 2000.

In a 2014 filing with regulators, Wentworth described its typical customer as "young, lower-middle income individuals," and said "executing repeat transactions" with them was a key growth strategy.

Historically, the company has spent more on marketing than any of its competitors — at least $700 million over the last three decades, according to documents filed with regulators when its stock was publicly traded.

Many of Wentworth's customers find them via its ubiquitous TV commercials, which feature the slogan "It's my money and I need it now!" The company has boasted that it spends five times its nearest competitor on television advertising.

Bobbi Jo Smith, right, said her mom, Bonnie Jo Smith, thinks she was "young and stupid" when she sold her $107,681 in payments for $32,000. But Bobbi Jo insists it was the right decision at the time.

Bobbi Jo Smith was 21 and trying to raise a child on a minimum wage job when she saw Wentworth's ads. Her mother warned her against selling her payments. "I know Mom thought I was young and stupid, but I believe I made the right decision for the circumstances I was in at the time," said Smith, who used the money to buy a car, attend cosmetology school and cover living expenses. "If I hadn't done that deal, I probably would have ended up living with my parents for the rest of my life."

Smith's mother, who set up the structured settlement after her daughter suffered a brain injury in a crash by a drunken driver in 2003, is still angry that Bobbi Jo received just $32,000 for $107,681 in payments. She has $6,000 left in future payments.

"I think they take advantage of people when they're in a vulnerable state. … If you rub candy in a kid's face, they're going to want it," Bonnie Jo Smith said.

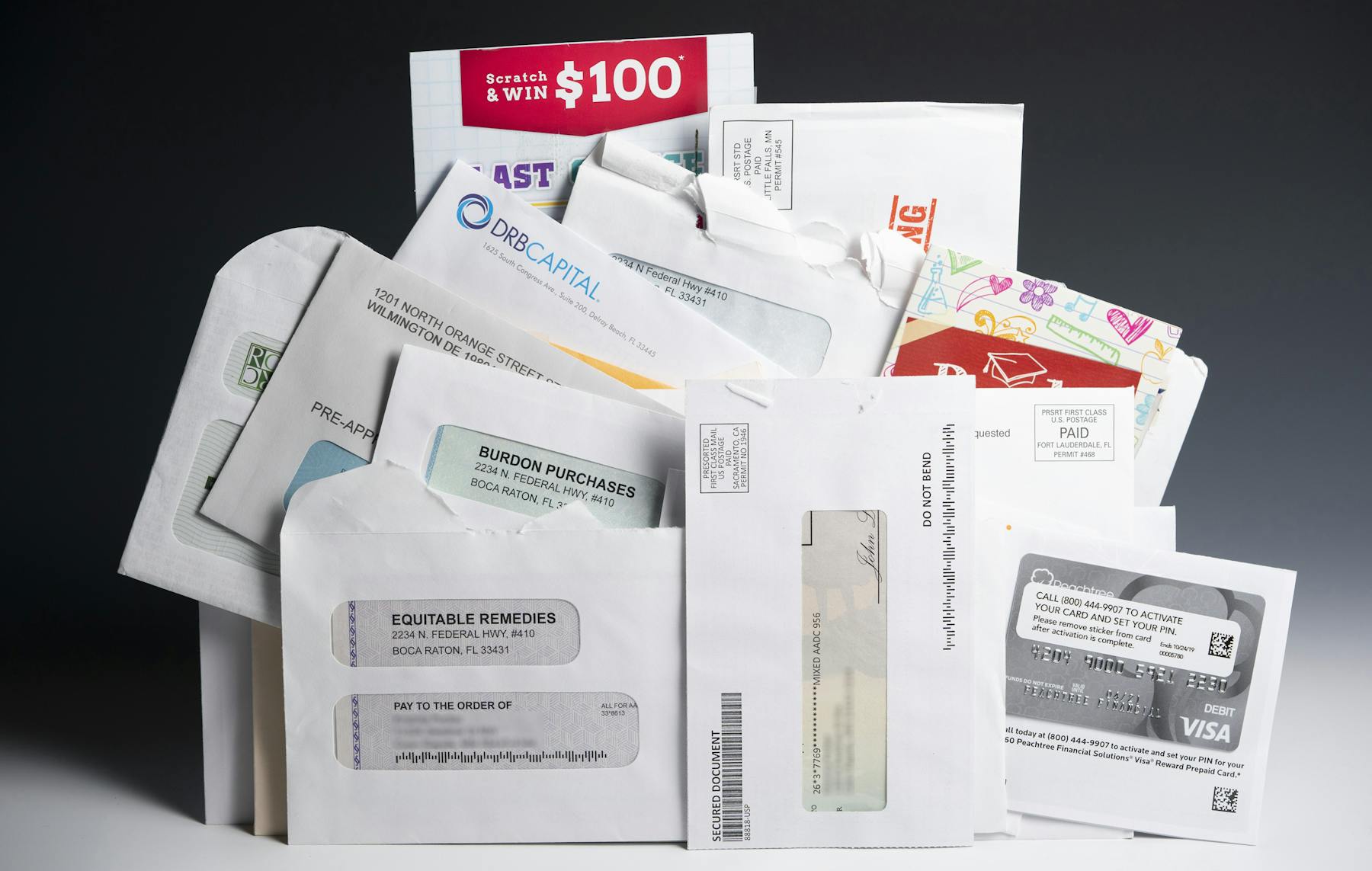

One Minnesotan who sold payments from her structured settlement three times receives piles of mail solicitations from companies seeking to buy more payments from her — this much in one month alone. Her name and address are blurred to protect her privacy. One company sends out thousands of fliers each week, its president said.

Once a purchasing company finds someone who has a structured settlement, they often go to great lengths to hide them from competitors.

Many firms obscure the identities of customers in Minnesota court records, often using initials instead of the customers' full names.

Records show that some firms have sued rivals that scrape court records and swoop in to offer a better deal before a transaction is approved by a judge. RSL Funding has been involved in legal battles with competitors over such practices for more than a decade. The Texas company's website features a 3½ minute video entitled, "You've likely been ripped off by J.G. Wentworth."

In one case, a company lawyer pressed Deborah Benaim, then senior vice president of Imperial Holdings, on whether the industry's trade group, NASP, prohibited members from offering each other's clients a better deal at the last minute.

Companies rely on repeat sellers

Terms are usually worse for people who sell settlement payments more than once.

Hover/tap for detail

Source: Star Tribune analysis of Minnesota district court cases

"If there's a signed contract, we don't interfere in each other's contract," Benaim said in a deposition. "I know that it's a policy of NASP … for as long as I've been involved in the structured settlement business."

In 2019, Louisiana lawmakers passed an anti-poaching law that prohibits structured settlement purchasing companies from offering sellers a better deal while a competitor's deal is awaiting court approval. Georgia and Nevada followed suit with their own anti-poaching laws in 2021.

The three laws also require settlement purchasers to register with the state and post $50,000 bonds that can be forfeited if companies engage in forbidden conduct. Violations could trigger revocation of a company's registration and even lead to stiff tax penalties that could make deals unfeasible.

NASP Executive Director Brian Dear said his group actively lobbied on behalf of the new laws, which he said will protect customers from "bad actors" by outlawing "forum shopping, false advertising and misrepresentation." He said the group will lobby other states, including Minnesota, to make similar changes.

But critics say the new laws will do little to deter abuse, noting that a single deal is often worth more than the entire bond of $50,000.

"The primary objective of the amendments appears to have been to discourage competition among factoring companies, by raising barriers to entry and by restricting 'poaching' of transactions," said Craig Ulman, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who represents insurance companies that set up the original structured settlements.

Big insurance companies have long frowned on the practice of buying and selling payments, arguing that annuities and other payment mechanisms provide a secure, lasting income. Through the 1990s they claimed that selling the payments was illegal, but judges generally sided with firms that buy future payments.

In 2017, after years of objecting to deals in court, Berkshire Hathaway Group Structured Settlements started its own operation aimed at offering customers more cash than they can typically get from companies that buy payments.

"We call it our hardship exchange program, and the reason we do it is we understand that people are taken in by the appeal of factoring companies," said Brennan Neville, a lawyer for BHG. "We view it as a means for them to do it in a more socially responsible manner."

While purchasing companies typically get a return equal to about 15% when they purchase a stream of payments, Berkshire Hathaway offers a rate of 6.5%, plus a $1,000 administrative fee if the transfer gets approval.

To illustrate the difference those percentages can make, take the case of Robert Tibbetts. Wentworth went to court in Beltrami County in 2018 to get a judge to approve Tibbetts' sale of $32,796 in future payments to J.G. Wentworth for $20,000.

Berkshire Hathaway objected. In a counteroffer presented to the court, the company offered to pay Tibbetts $20,000 if he was willing to give Berkshire Hathaway $25,353 in future payments. That would allow Tibbetts to keep nearly $7,500 in extra payments.

A judge still approved the deal with J.G. Wentworth less than three weeks later. But Neville said his company has made headway with customers and has done nearly 100 deals of its own.

"This is not a moneymaker for us," Neville said. "But we recognize that there are situations where people are going to have problems, and we would rather they come to us than go to a third party that's going to take their money at 15 percent."

Any sale of settlement payments creates a public record where none previously existed. That person is quickly added to the prospect list of dozens of firms, each eager to persuade them to sell even more of their payments. That's when the soliciting begins.

Phone calls. Texts. Facebook messages. Mailings promising gift cards worth $25, $50 or $100 if you call a toll free number and confirm that you are still receiving payments. Visa gift cards worth $250 if you sign a contract to sell those payments.

Wayne Ludvigson, who received a settlement after his mother's death, says he repeatedly asks companies to stop calling.

Wayne Ludvigson, who first sold some of his settlement money in 2011, collected a total of 44 mail solicitations in the first three months of 2021. Many of the appeals suggested he had been ripped off on his previous sale and urged him to act quickly before the offers expired.

Six of the solicitations were tailored for people whose finances are hurting from the pandemic.

"NEED MORE STIMULUS?" asked DRB Capital, in a letter accompanying three checks worth more than $2,000. "Today is your lucky day. … Call now to get your checks activated."

American Annuity Funding, a Florida-based company, sent him a $500 "stimulus check" that was valid "only to persons who execute a full contract with American Annuity Funding in which you agree to sell us future structured settlement payments that you have not previously sold or agree to sell to anyone else."

Ludvigson ended up selling almost half of the $236,000 settlement he received over a medical malpractice claim involving the death of his mother. He received a total of $21,141, which represented just under 50% of the estimated present value of those payments in the first sale, about 27% in the second and less than 15% in the third.

Ludvigson, who won't see another monthly payment until the year 2035, says he has repeatedly asked companies to stop contacting him.

"I tried to explain to them … that this is the type of case that's more emotionally sensitive," he said. "I really don't like being reminded of it all the time."

In a written response to questions, DRB said it is "fully committed to protecting the interests of our customers."

"As an industry leader, we have well-established policies and procedures that adhere to all laws and regulations, and we conduct a comprehensive 'do not call' procedure that allows consumers to 'opt-out' of marketing programs," the company said in the statement, which was provided by NASP, the trade group. "Through NASP, DRB continually advocates for strengthened consumer protections, including requiring registration of structured settlement purchasers and establishing laws that protect the personal information of individuals seeking to transfer portions of their settlements."

In New Mexico, Peachtree's aggressive tactics persuaded Perstine Tsosie to cancel her deal with the company and cut a deal with a competitor, even though that company couldn't come close to matching Peachtree's offer, court records show. At a 2019 court hearing, a New Mexico judge pressed Tsosie on the issue, noting she was losing more than $90,000 by switching firms. She was adamant.

"Over the course of approximately three months, they have harassed me by calling hundreds of times at all hours of the day," Tsosie said in a subsequent letter to the judge. "Due to Peachtree's lack of respect, they have put me and my family in a worse situation than we were months ago with their … lies and their selfishness."

In court, Peachtree acknowledged that the company attempted to contact Tsosie in an attempt to "renegotiate" the faltering deal, but the judge denied Peachtree's request to enforce its original contract.

Mantorville resident Coty Allen says he has gotten 10 to 15 phone calls a day from companies that want to buy part of the $51,417 he received through an out-of-court settlement over the death of his mother when he was 8. He changed his number and signed up for the federal "Do Not Call" register, but after a few months of silence, the calls began again.

"It is very annoying," Allen said. "They say, 'We'll put you on the no-contact list,' and then the next day it is the same. … They're con artists, in my opinion."

Allen sold the last of his payments in 2014. The calls continue.

About the series

Unsettled is a Star Tribune special report examining how companies obtain court approval to purchase payments intended to help accident victims recover from their injuries. The series was largely reported in 2019 but publication was delayed when the pandemic struck in early 2020. Additional reporting was conducted in 2020 and 2021.

Part 4: The Guardians

In New Mexico, some judges routinely appoint guardians to look into whether a deal makes sense for the seller, leading to far lower approval rates.

SERIES CREDITS

Reporting: Jeffrey Meitrodt, Nicole Norfleet and Adam Belz

Illustration: Brock Kaplan

Photos and videos: Jeff Wheeler, Mark Vancleave and Cheryl Diaz Meyer

Development: Thomas Oide

Design: Dave Braunger, Anna Boone, Josh Penrod

Graphics: C.J. Sinner

Editing: Eric Wieffering and Thom Kupper

Copy editing: Lisa Legge, Ginny Greene and Catherine Preus

Digital engagement: Anna Ta, Ashley Miller and Tom Horgen

ABOUT THE DATA

Applications to buy settlement payments are public record, and the Star Tribune reviewed more than 1,700 individual case filings in Minnesota courts over the last 20 years. We compiled a database with information on each case, including the company that bought the payments; the financial terms if available; the district court and presiding judge; whether the case was approved, denied, dismissed or pending, and notable details about the person filing to sell their settlement.

To measure individual outcomes, we filtered the data to about 1,200 sales that judges approved. We summarized those deals by person, identifying about 800 individuals who made at least one sale, including the total amount they sold and received. We removed people for whom we didn't have financial details from all of their sales. This left nearly 700 people for whom we calculated the total percent of money they received against what they would have received had they not sold any payments.