Finding their stride

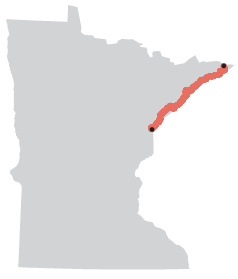

My camping experiment was not going well. After four days trekking through Duluth and its environs, the trail finally led us out into the wilderness. And it was here, marching toward the North Shore's famed Sawtooth Mountains, that I'd decided to try to become a "real" backpacker. That is, one who slept trailside, nodding off to the soothing sounds of hooting owls and gently creaking trees, and waking to the songbirds' reveille.

The idea seemed so romantic. And practical. When you stayed in motels nightly, as I typically did, you needed to shuttle on and off the trail every morning and evening. While motels certainly offered numerous comforts — namely, hot showers and soft beds — dipping in and out of humanity daily disrupted the peaceful rhythm of life on the trail. But I was struggling with the transition.

The first night, we set up camp at Big Bend, a site tucked near a branch of the Knife River. While readying for bed, my husband, Ed, spotted a tick — on my derrière, of all places. Screaming and flailing ensued. Then, climbing into my hammock, I accidentally sat in its unsupported underquilt, promptly crashing to the ground. Now ensnared in the bug net that enveloped the hammock, I thrashed around like a trapped animal. There were more howls, punctuated by one well-placed curse.

We spent our second night at Reeves Falls. While the campsite was attractively perched above a stream with its own pint-sized waterfall, the approach was a rocky, swampy morass, making trips to wash up and filter water unpleasant. And when I opted to bunk in the tent with Ed, I discovered the site's tent pad — a spot of earth cleared for campers — sat at a severe slant. All night I felt on the verge of sliding head-first into the scrub.

Then, on my third attempt at becoming one with the trail, I planned a stop at one of the four Gooseberry campsites, strung in a row along the Gooseberry River. But all four sites were full, so we pitched our tent on a flat piece of ground adjacent to the East Gooseberry site. With no fire ring or bench for relaxation, we tucked in early, only to awake to the light staccato of rain on our tarp. As we dispiritedly began packing up our sodden, muddy tent, the skies opened up in a dismal crescendo.

"We're going to a motel tonight," I said.

We marched downhill in the rain toward Gooseberry Falls, the second of eight state parks linked by the Superior Hiking Trail. Three miles of the Gooseberry River wind through the park and across its rocky ledges, ridges and bluffs, dramatically sculpted from an ancient lava flow. As the water races toward Lake Superior, it plunges 240 feet via five dramatic waterfalls.

The rain stopped when we reached the park's Fifth Falls viewing area, perking up our flagging spirits. And it was there, after snapping countless photos, that I met BlueBerry. The young, dark-haired man was clad in tights, a navy floral skirt and a long-sleeved shirt. A modest pack was affixed to his back, while a long, pink-and-cream scarf was loosely knotted around his neck. Because he introduced himself as BlueBerry, I replied I was Snowshoe. And just like that, we were kin.

Encountering hikers

"BlueBerry" and "Snowshoe" are trail names — monikers long-distance hikers adopt or that are bestowed upon them by others. Having a trail name is like a secret handshake. It shows you know the power of a PocketRocket, that an Osprey is not a hawk, and that Big Agnes and Gregory are quite the couple. So our conversation flowed in a predictable manner: Are you thru-hiking or section-hiking? How many miles a day are you averaging? What other trails have you hiked? How did you get your trail name? Where's your next hike?

BlueBerry, 23, hailed from Alabama. He received his name while on the 2,185-mile Appalachian Trail because his purple poncho billowed around him as he walked. The hiking skirt? More comfortable than shorts. The scarf? A gift his mom intended to mail to someone else. But he never sent it back because he discovered its versatility as a blanket, sun shield, hat and mosquito net.

Known as Cameron Loew off-trail, BlueBerry was here with Green Tortuga, a friend from the Appalachian Trail who lives in Seattle. Green Tortuga (aka Ryan Carpenter), who joined us shortly, once worked at Intel as a software engineer. But the 42-year-old lost his job in 2001, when the dot-com bubble burst. So with nothing but time on his hands, he pursued a dream: thru-hiking epic trails like the Appalachian and Pacific Crest. Along the way, he began creating websites such as The Soda Can Stove and Walking 4 Fun that allowed him to turn his passion into a job.

BlueBerry and Green Tortuga were the first two thru-hikers I met, "thru-hiker" being the term for someone who hikes a long-distance trail in one attempt. I'd already encountered a half-dozen section-hikers — folks who hike a long-distance trail in small chunks over time. Running into eight serious hikers in a week might not seem like a lot, but those were impressive numbers.

A surge of hikers

Percentage of young adults 18-24 who hiked in 2016, according to a 2017 Outdoor Foundation report. Hiking was the second most-popular activity behind running, jogging and trail running (31 percent).

Thru-hikers of the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail between 2010-present, according to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

The percentage increase from the number of Appalachian Trail thru-hikers in the 2000s (5951 hikers).

While hiking is part of the culture in countries such as Switzerland and New Zealand, it has never been popular in the United States. Until recently, that is. While no one knows exactly why Americans are suddenly heading into the woods, at least part of the reason can be traced to "Wild," a 2012 book by Cheryl Strayed that details her trek on the Pacific Crest Trail.

The Pacific Crest Trail issued 1,879 hiking permits the following year. By 2017, that number had soared to 6,069. Similarly, 1,982 hikers set out to complete the Appalachian Trail in 2011. In five years, that number doubled.

While the Superior Hiking Trail isn't as well-known as the Appalachian or Pacific Crest, it's also experiencing a surge in popularity. Jo Swanson, development director at the Superior Hiking Trail Association, said the group doesn't track the number of hikers on the trail. But there's solid evidence more and more people are using it.

"Trail maintenance supervisors used to re-dig 10 latrines a year out of the 94 at our campsites," she said. "Now, they have to re-dig almost half of our latrines in any given year."

The day I met BlueBerry and Green Tortuga, we hiked together for several hours while Ed stepped off the trail to secure the motel room I coveted. We climbed up and around the sheer red rocks lining the Split Rock River's western flank, waded through its rushing waters, then marched 2 miles down its eastern half before parting ways.

That night, smelling sweetly of lemon verbena, I pulled crisp, white bedsheets up under my chin. I was happy to be clean and comfortable, but I missed the scent of damp leaves and pine needles. And I would have much preferred falling asleep to the soft rushing of the Split Rock River, where we had planned to camp, than to the abrupt belching of the room's air conditioner.

Melanie Radzicki McManus wrote "Thousand-Miler: Adventures Hiking the Ice Age Trail." She lives near Madison, Wis.