Goodbye embrace

Great clouds of dust billowed above the Arrowhead Trail, compliments of Harriet Quarles' shuttle van. As she raced up the gravel road leading to the Otter Lake trailhead, with me in her wake, tears blurred my vision. Clumsily wiping them away with my hand, I willed myself to focus on the dust clouds, which were all I could see of Harriet.

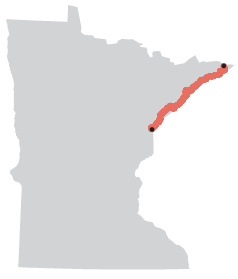

I was two days out from finishing the Superior Hiking Trail. The plan was to drop my car at Otter Lake, where a 1.2-mile trail and spur led to the northern terminus at a point called the 270 Degree Overlook, a rocky outcrop facing the Canadian border. Then Harriet would ferry me back to Camp 20 Road and the beginning of the end.

I was ready to be finished with my thru-hike, so why the tears? Sometimes on a long-distance hike, you don't want the trek to end. Other times you can't wait to get off the trail and back home. On this hike, the trail and I were in sync. Just as I was feeling like it was time to say adieu, the trail appeared to be bidding me a fond farewell. And it was touching.

Yesterday, my hike had begun with a lake walk along a remote stretch of Superior's shoreline. I wobbled and bobbled along the smooth stones, marveling at the pristine beach and the lake's crystal-clear waters. Lake Superior was impressive when viewed from aeries like Pincushion Mountain and Carlton Peak, to be sure. But walking on these stones, touching the cold water, was an intimate experience. And it hearkened back to Day 3, the only other time the trail unspooled along the lakeshore. That day, walking amid crowds of happy beachgoers in Duluth, the feeling was celebratory — a cheery "welcome to the trail" vibe. Here, stumbling along in solitude and peace, it felt like the trail's namesake body of water was giving me a warm, goodbye embrace.

After my wistful parting from Lake Superior, the path turned inland, nudging me away from the water and into the woods. Just as my start at the trail's southern terminus was a do-si-do to Wisconsin, Minnesota's neighbor to the east, my arrival at the opposing terminus would involve a salute to our Canadian neighbors to the north. The perfect bookend to my hike.

I'd dried my tears by the time Harriet and I hugged goodbye on Camp 20 Road. As her van disappeared in another dusty swirl, I turned and stepped onto the trail.

Soldiering on

After yesterday's tender farewell, I wasn't prepared for brutality. But that's what I got. The mosquitoes were unrelenting. An ungroomed trail detour masquerading as the real thing confounded me for about 20 minutes. So did a logging area, where the blazes played hide-and-seek. When I finally reached my Jackson Creek campsite and shook my tent from its nylon bag, it plopped out along with a gallon of water — I'd never dried it out after the rainy morning at Gooseberry Falls.

The following day, the guidebook said I'd hit the trail's highest point, 1,829-foot Rosebush Ridge, then be treated to a "predominantly flat" section of trail that wound through open meadows. It sounded lovely. But climbing the ridge was hard. There was no view at the top. The open meadows may have been flat, but they were also overgrown, deeply potholed and difficult to traverse. The mosquitoes continued to attack, necessitating full-body netting. A mother grouse threatened me.

This trail wasn't going to give up. It was going to be tough every single step of the way. And you know what? That was OK. Because the trail had given me so much more to compensate for its hills, mud, rocks and roots. It took away my stress. It treated me to moments of great beauty and joy. And it gave me time to be alone with myself and my thoughts, a rare occurrence in our fast-paced lives.

So what did my introspection bring? The knowledge that this trail, and others like it, are great gifts. And we can't take without giving back.

Thankfully, the Superior Hiking Trail Association has upward of 300 volunteers who pitch in each year. Some are "trail adopters," who clear trees and brush from portions of the trail in advance of the spring and fall hiking seasons. Others clean up campsites or show up for group gatherings to tackle bigger jobs.

"Volunteer help is a huge boon to the association," said Denny Caneff, executive director. "There would be no Superior Hiking Trail without them." The big need, he said, is money.

BIG BAD FIVE

The Superior Hiking Trail Association has designated five locations — its

Trail usage is free; so are its 90-plus campsites. But what many hikers don't realize is that the nonprofit association does not receive any direct state or federal financial support. So while it's invaluable that there are hundreds of volunteers, the association still needs cash — and lots of it. Caneff said replacing the missing bridge over the Split Rock River could top $100,000 — partly due to the need to hire a helicopter to fly materials to the site — while renewing the Split Rock River loop trail to reach the new bridge could cost another $50,000 to $75,000. And while it's fantastic that trail usage is rising, more hikers mean more wear and tear on the path, and thus more maintenance needs down the road.

Caneff estimated about 5 percent of the people who use the trail donate to the association. "That means about 5,000 people subsidize the trail for the other scores of thousands of users," he said.

The solution is clear. If we're willing to shell out $10 to see a movie, or $50 to enjoy a meal out, let's donate to our trails every time we use them. No, it's not required. But we need to pay it forward for those following our boot prints.

Success

It was just before noon June 21 when I finally climbed up to the 270 Degree Overlook and the Superior Hiking Trail's northern terminus. I was ecstatic at my accomplishment and relieved to be finished. The view was expansive and impressive; what else would you expect from this trail?

"I did it! Victory over a hard trail," I scrawled in the register, along with an early congrats to Green Tortuga and BlueBerry, who would arrive here five days later. Picking my way down the spur back to the main path, I paused before a small sign. It said the Border Route Trail began right here, where the Superior Hiking Trail ended, unrolling westward through the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

Hmm. The Border Route Trail …

Melanie Radzicki McManus is a freelance writer. Her book "Thousand-Miler" chronicles her thru-hike of Wisconsin's Ice Age National Scenic Trail. She lives near Madison, Wis. Reach her at melanie1mcmanus@gmail.com.